Why are the rules about foul balls so weird?

In most major sports, the rules around whether or not the ball is in play are pretty straightforward: If it*s on one side of a line, it*s in play. It it*s on the other side of that line, it*s out of play. In baseball, however, it*s not quite that simple.

You probably know the rules about fair and foul balls, but here*s a little refresher just in case. From the MLB Rulebook:

※A FOUL BALL is a batted ball that settles on foul territory between home and first base, or between home and third base, or that bounds past first or third base on or over foul territory, or that first falls on foul territory beyond first or third base, or that, while on or over foul territory, touches the person of an umpire or player, or any object foreign to the natural ground.※

Those are far more words than one would expect for a matter as seemingly simple as whether a ball is in or out of bounds. What sticks out most is that the rules are different depending on where the ball is on the field. That*s weird. The rules for a foul ball in the infield are not the same ones that govern balls in the outfield. That*s like if the sideline was treated as different from the baseline on a basketball court. It*s hard to even think about what that would look like because it*s so crazy.

But, those are how the rules work in baseball and, it turns out, there*s a good reason for it.

You see, the rules weren*t always this weird. Back in the early days of baseball in the 19th century # well, there were a lot of different sets of rules floating around. But the prevailing rules held that a ball was fair if it first touched ground in fair territory and foul if it first touched ground in foul territory. In other words, the rules that currently govern the outfield governed the entire field.

Like every other sport, the boundaries meant the same thing everywhere. Then something happened that threatened to break baseball.

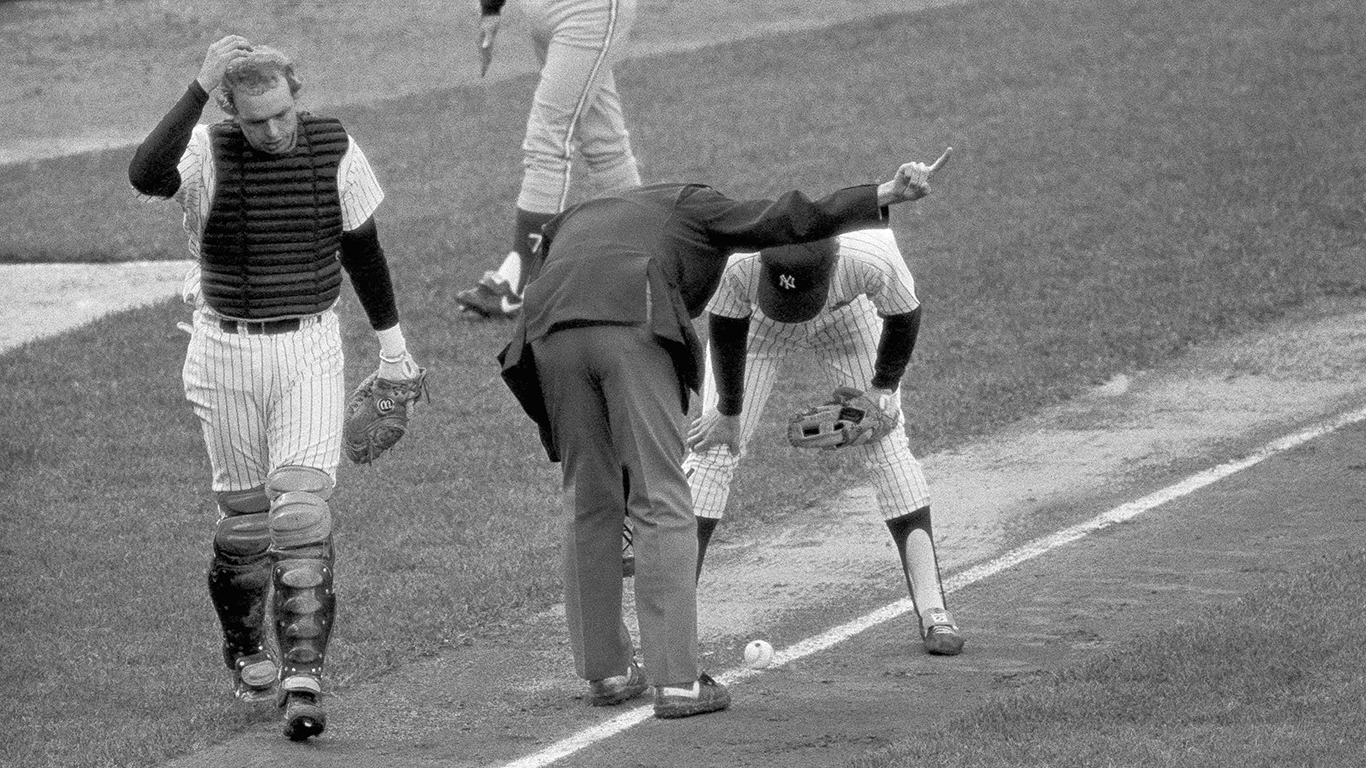

In the 1870s, the batter was able to choose whether he wanted the pitcher to throw a high ball or a low ball. With this rule, some hitters began to develop a certain type of swing. They would call for a low pitch and chop down on it to create some pretty wicked spin 每 or ※English§ as they called it 每 that caused the ball to land fair just in front of home plate then dart off into foul territory. As long as it landed fair first, it was in play, forcing fielders to chase down balls nowhere near what we would think of as the field of play.

The strategy was called the ※fair-foul bunt,§ but it*s probably best to not think of it like a bunt to get to first base. The fair-foul bunt produced more than just singles. If a player struck the ball properly and it bounced off the home plate 每 which was made of cast iron at the time 每 in just the right way, it could bounce quite a ways, sometimes even under the stands. It was perhaps the world*s first cheat code.

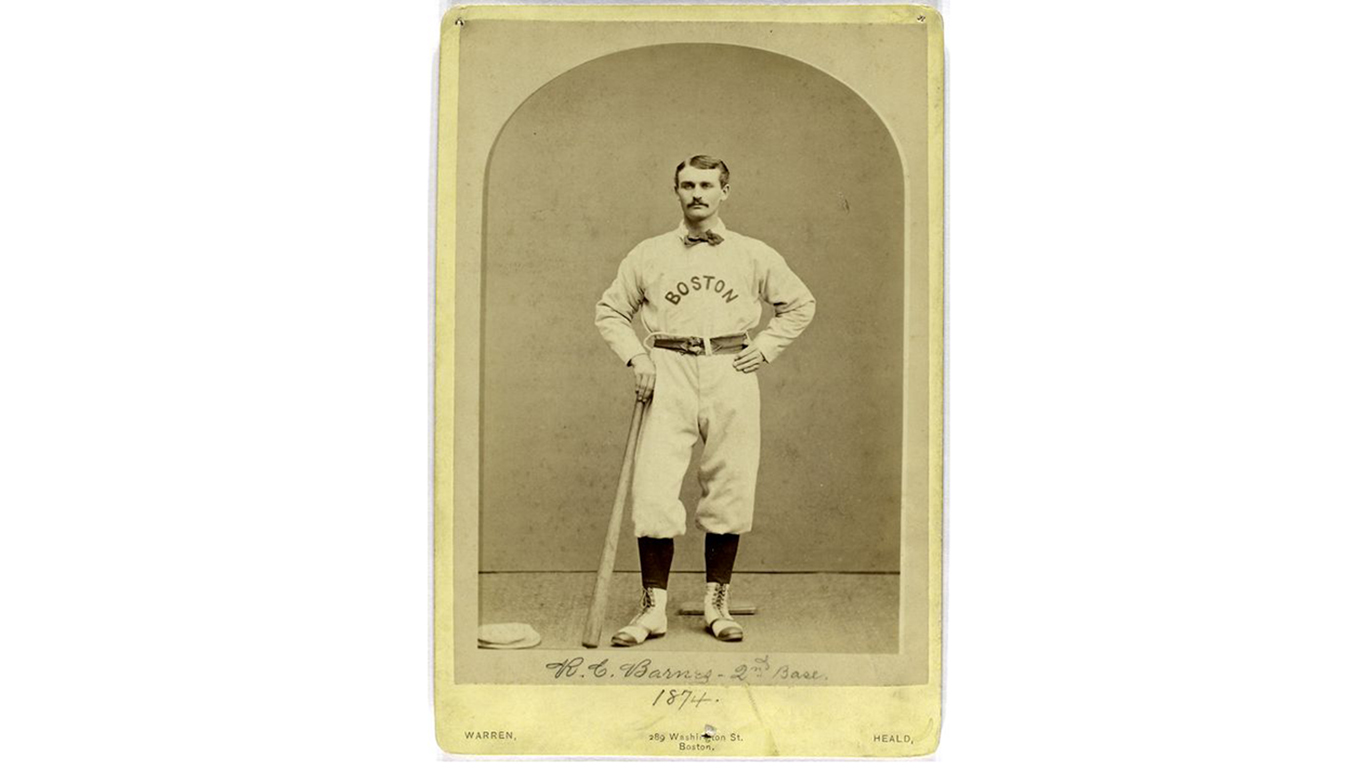

No one was better at this technique than Ross Barnes, a second baseman for the Boston Red Stockings. He was a savant of fair-foul bunting, employing the strategy to such great effect that he led the league in hitting three separate times. While most players engaged in more of a bunting motion, it*s probably more accurate to label Barnes* technique ※hitting.§ According to the Chicago Tribune, ※[Barnes] always hits [the fair-foul] with a full swing of the bat, and just as hard as he strikes any other kind of ball.§ Barnes was not living off bunt singles.

He hit .401 in his first season in 1871, then followed that up by hitting .430 the next year # and .431 the year after that. And he didn*t just lead the league in batting average, he also led the league in slugging and OPS in 1872 and &73.

While today's best hitters hit the ball hard into the outfield and over the fence for home runs, Barnes just went up to the plate, called for a low pitch, chopped down on it and ran the bases while fielders chased down the ball. And when players shifted to try to defend the fair-foul bunt, he would take advantage of the alignment with a ※normal§ hit. He was legitimately the best hitter in baseball thanks to his mastery of the fair-foul bunt.

Barnes was single-handedly destroying baseball. His Red Stockings went a combined 205-50 from 1872-75, a rate equivalent to winning about 130 games during the current 162-game regular season. The 2018 Red Sox were dominant during the regular season. They only won 108 games.

Clearly, something had to change. And, so, the tinkering began.

They moved home plate into foul territory so Barnes couldn*t aim for it. They moved the batter*s box back into foul territory so Barnes couldn*t just chop straight down on the ball and land it fair. But Barnes kept hitting and the Red Stockings kept winning.

Finally, they changed the rules to eliminate the fair-foul bunt. Starting in 1877, the ball had to remain in fair territory past first or third base to be ruled a fair ball 每 the same rules we have today. In other words, the fair-foul bunt became, simply, a foul bunt.

Barnes fell seriously ill that season, so we may never know how much his .272 batting average that season was due to the rule change and how much was because of the illness. Either way, he never hit over .300 again. And baseball*s glitch was patched.

Baseball*s rules for fair and foul balls are, admittedly, more complicated than you*d want them to be. Out of bounds in basketball doesn*t require much explanation, but why some balls that bounce into foul territory are fair while others are foul does. For that, we have Ross Barnes to thank.