Part one of a two-part investigation into lefties in baseball. Read part two, on pitchers, here.

Where have all the lefty hitters gone?

This is the wrong question, actually. But it's where this starts, and trust us, it's going to take us to the right place.

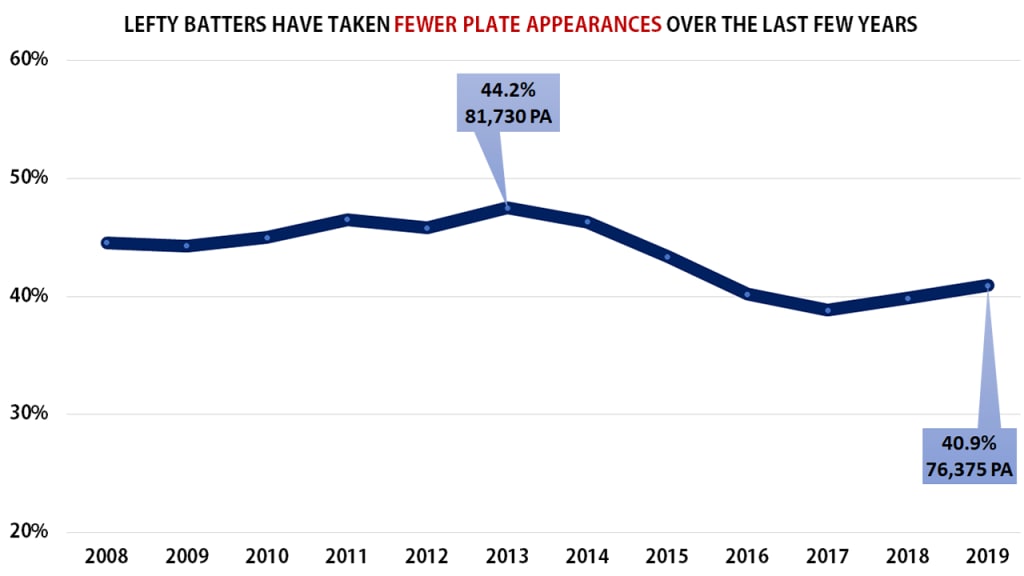

Take 2009, for example. That year, there were 82,511 plate appearances from lefty hitters. In 2019, there were just 76,375. That's a drop of 6,136 lefty plate appearances in a decade, or more than 7%. It's a lot.

Given that the entire Cleveland roster had 6,124 plate appearances last year, it basically amounts to an entire team of lefty hitters turning right-handed over a decade.

Looking at it on a rate basis, 40.9% of plate appearances came from lefties in 2019. That's part of a trend where the last half-decade was lower than the half-decade before it, and while it was indeed slightly lower back in 2006, it hadn't that been low since 1983. It's especially true in the American League, which had been in the 46-47% range each year from 2011-14, but dropped down as low as 38.8% in '17. (This is going to be important later.)

So: Why? Where are the lefty hitters? We have some ideas, and this is something to keep in mind when you watch the Draft on June 10 and 11, as this shift is impacting the game at all levels.

Maybe it's the shift.

Our first thought was, "Well, it's the shift, obviously." Obviously!

That's because the shift is something that A) has become far more prevalent in recent seasons, and B) disproportionately affects lefty hitters (who were shifted on 42% of pitches in 2019) more than righties (just 14%).

If you hit ground balls, it's probably the worst time in history to be a lefty hitter. Then again, lefties get their own advantages, like the added platoon advantage based on the fact that 72% of pitches last year came from right-handers, or that they get to stand slightly closer to first base when they bat, or that they've traditionally been preferred defensively at first base. It's not like there's not successful lefty hitters today; just ask Cody Bellinger or Christian Yelich or Joey Gallo or Bryce Harper.

There's probably a little to this theory, though not nearly satisfying enough to answer our question. But in the process of investigating this, we realized something. Yelich throws righty. So does Gallo. So does Harper. So do lefty swingers Max Muncy, Michael Conforto, Rafael Devers and Matt Carpenter.

That realization made us ask a much better question, the one that really seems like it matters.

Where have all the lefty throwers gone?

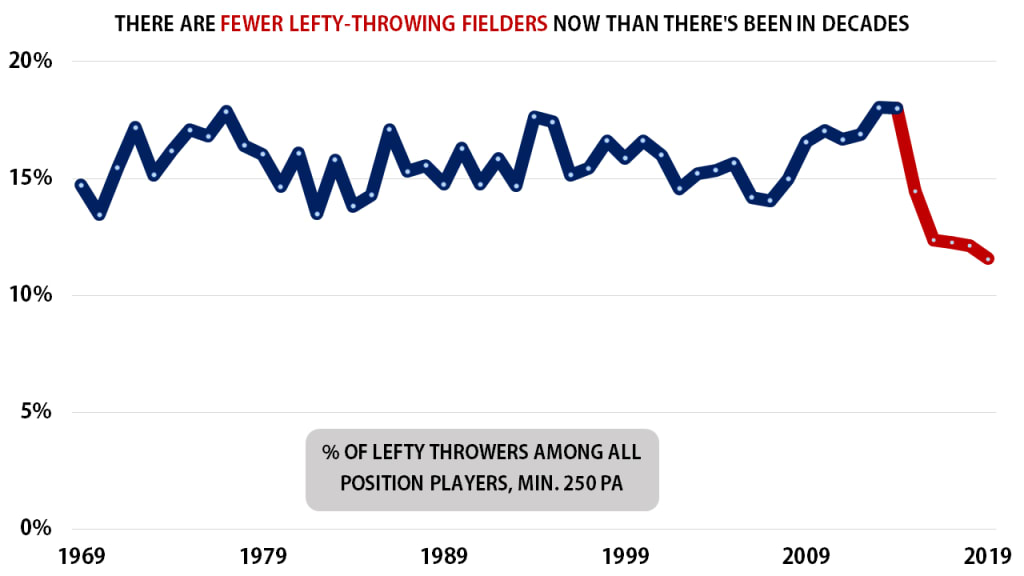

Forget the batting side for a second, and focus just on throwing hand for position players, not pitchers. Last year, there were 37 semi-regular players (minimum 250 plate appearances) who threw left-handed, like Bellinger, Charlie Blackmon or Juan Soto. But there were 320 total players who collected that many plate appearances, which means that only 11.6% of semi-regular non-pitchers in baseball threw left-handed. That's the culmination of a steady, multi-season drop since a recent peak of 18% in 2013 and '14, but more importantly, that's the lowest number since 1964, nearly six decades ago.

Now, it's possible that this too has to do with the shift. After all, fewer lefty hitters might also mean fewer lefty throwers, right?

Sure. Maybe. But we found something else to explain this, too.

Maybe it's about positional versatility.

As pitching staffs have expanded and bench spots have contracted, the appeal of players who can handle multiple defensive spots -- think Enrique Hern¨¢ndez, Chris Taylor or Brock Holt -- has increased. That's a natural bias against lefty throwers, who aren't considered options to play catcher or three of the four infield spots. That's always been true, of course, but shorter benches and a desire for "the next Ben Zobrist" might make it more true.

To choose one combination of positions as an example: Last year, eight players got into at least five games at each of second base, third base, left field and right field. It was the second most behind 2016, and it's one of just four seasons ever where seven players did that ... with those four seasons being 2016, '17, '18 and '19. Lefty throwers, again, can't do this.

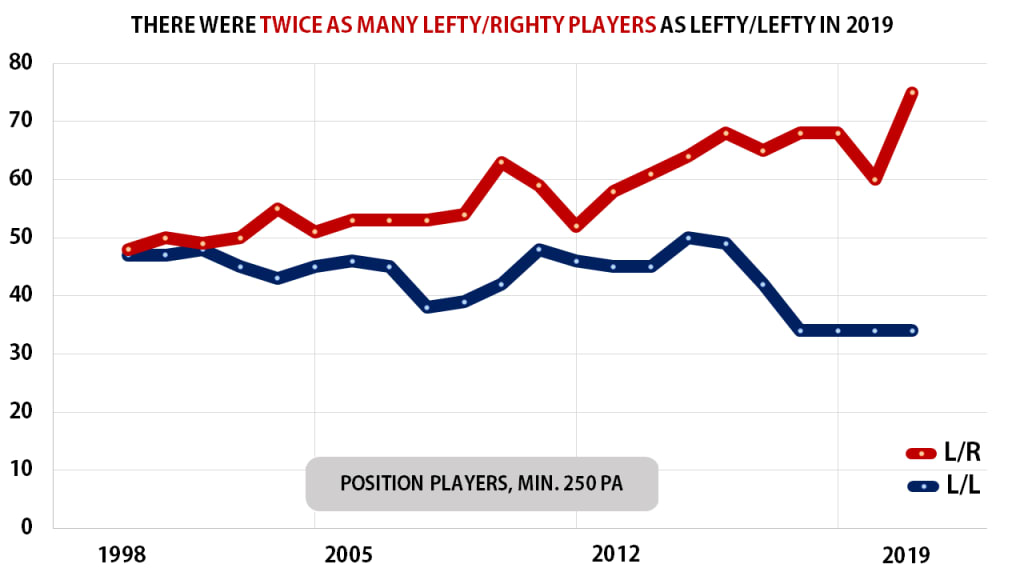

Still, you need to have some lefties swinging the bat, and there's plenty of versatile lefty swingers who throw righty, like Muncy or Jeff McNeil or Holt, which leads us to what's maybe the real issue: It's not just that there are fewer lefty hitters. It's that there are fewer pure lefties. That is, in 2019, as in each of the previous three seasons, there were 34 lefty hitter/throwers who got 250 plate appearances, which was the lowest number in a non-strike season since 1969 -- when there were six fewer teams.

Meanwhile, there were 75 players who hit lefty and threw righty, which we like to think of as "the Ted Williams," which was the most ... ever. Ever!

If we look at that gap in the 30-team era, the trend is clear. In 1998, there were a nearly equal 47 full-lefty players and 48 lefty-swinging/righty-throwing players. Those numbers slowly separated over the years, really began to jump apart in 2015, and by last year there were more than twice as many lefty/righties than pure lefties.

(While there are also switch-hitters not included here, we're not seeing any sort of surge in switch-hitting; quite the opposite, really. There were 39 who got 250 plate appearances last year, but in the 1990s, we'd often see 50 or 60 such players.)

If you can't have lefty throwers playing some of the most important positions ... and you have fewer players to man those positions ... but you also can't simply not have lefty hitters ... this is how you do it. More lefty swingers saw at least 10% of their playing time coming at the non-lefty infield spots (second, short, or third) last year than at any time in Major League history -- and the top eight years are the last eight years.

Seasons with most lefty hitters playing 10% of their time at 2B, SS or 3B

Min. 250 total plate appearances

35 -- 2019

33 -- 2015

31 -- 2014

29 -- 2017

28 -- 2016, 2013

25 -- 2018

21 -- 2012, 2008

Question answered, right? Sort of! But ...

Maybe it's because first base doesn't just belong to lefties anymore.

That's because it's not happening just at spots where lefty throwers can't play. This is also affecting first base, too, long the home of the archetypal "sweet swinging, good defense" lefty, the type who would post high batting averages and look good doing it, while offering good-not-great power. (Think Keith Hernandez, Mark Grace and John Olerud, though obviously powerful lefties like Will Clark, Todd Helton and Don Mattingly have starred there as well.)

"All things being equal," former player and broadcaster Tim McCarver told the New York Times in 2009, "you¡¯d rather have a lefty at first base.¡± It's never been hard to understand why. Lefty first basemen can more easily throw across the diamond without turning their bodies. Then again, how often are first baseman really asked to throw? Not that often, comparatively. Left-handed first baseman are also better suited for a quick tag on a pick-off attempt, but stolen bases are no longer a huge part of the game, so that's no longer a huge consideration, either.

"No," said one current assistant GM when asked whether he took fielding hand in consideration at all when considering first basemen. "It's not a decision being made with defense in mind."

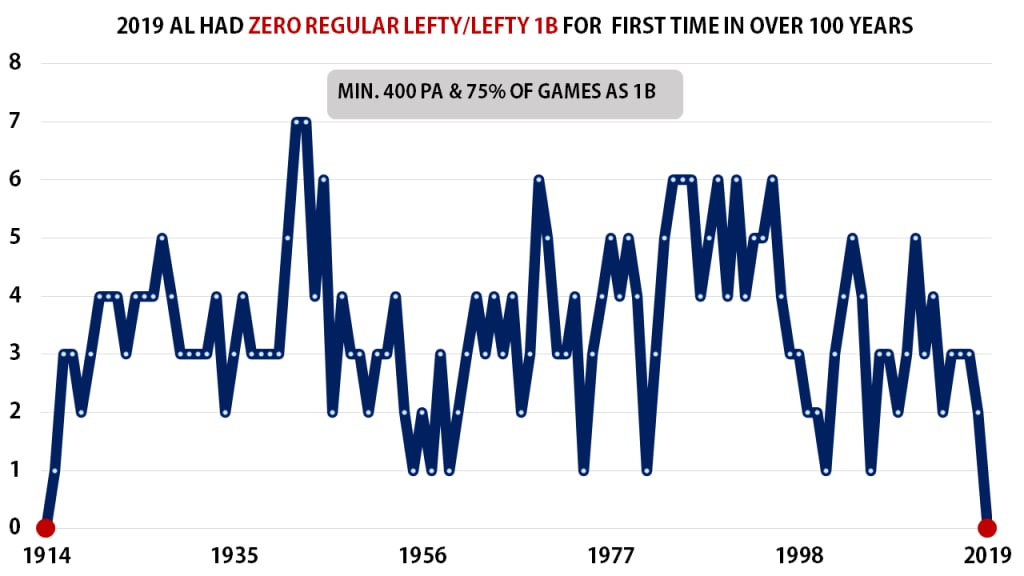

To that end, the American League just did something that hadn't been done in more than a century. In 2019, there wasn't a single lefty/lefty first baseman -- not one! -- to receive 400 plate appearances. (In fact, only four AL lefty/lefty first basemen received any sort of playing time, and one of them, Jared Walsh, was a two-way player who pitched in five games.) That hadn't happened since 1914, Babe Ruth's rookie season, when there were only eight teams playing 154-game seasons in a sport that only vaguely resembles the baseball we know today.

If you expand that to the National League, you'll see that only three lefty/lefty first basemen received 400 plate appearances in 2019: Anthony Rizzo, Brandon Belt and Eric Hosmer. While Rizzo is a star, the fact that Hosmer can't play other positions and Belt shouldn't -- and that neither really hit, anyway -- are limiting factors on their team's offenses.

Setting aside the 1981 shortened season, a number that low -- just three lefty/lefty first basemen getting 400 plate appearances -- hadn't been seen since 1959. (Even then, barely, as an aging Stan Musial got 404 chances at the plate.) Before that, it hadn't happened since 1918. For anyone less than a century old, this is basically unprecedented. You've never seen baseball like this.

Now, it's all possible that it's a fluke, a random occurrence, of course. Maybe it's cyclical. Maybe it'll bounce back.

Except ...

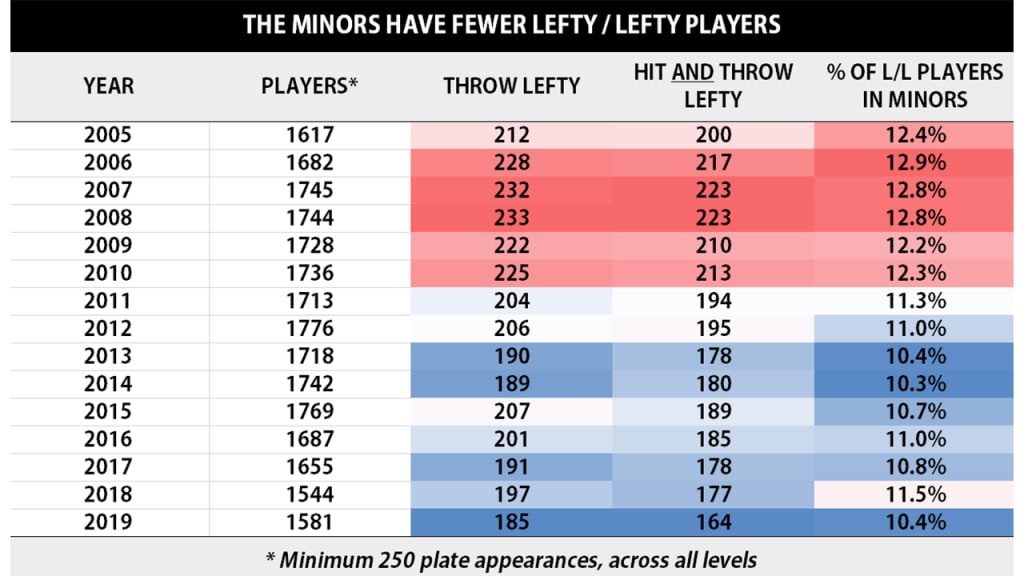

... this isn't just happening at the Major League level. Let's go take a spin around the Minor Leagues, looking for all lefty/lefty players who received at least 250 plate appearances dating back to 2005. Last year, there were 164 such players, the lowest of the 15 years we have data for, with the peak being 223 in '07 and '08.

At MLB Pipeline, 22 of the top 100 prospects are left-handed hitters. Yet, of those 22, just seven throw lefty, while 15, or more than two-thirds, throw righty. (That's more than double. There's also Seattle first base prospect Evan White, who boasts the rarely seen "righty hitter, lefty thrower" toolset, though that's another discussion entirely.) Just one of the top 10 first basemen -- Miami's Lewin Diaz -- is a pure lefty.

Look at amateur levels, too. MLB Pipeline has a list of the Top 150 Draft prospects for next month's Draft, and the top three lefty hitters (No. 6 Garrett Mitchell, No. 7 Zac Veen and No. 10 Heston Kjerstad) all throw righty. All told, the Top 150 breaks down like this.

2020 MLB Pipeline Top 150

Hitters: 71 of 150 (47%)

Lefty hitters: 30 of 71 (42%)

Lefty/lefty hitters: 9 of 71 (13%)

Lefty/righty hitters: 21 of 71 (30%)

Once again, more than twice as many lefty/righty hitters than pure lefties. Of those nine, eight are outfielders, and then way down at No. 137, the only first baseman, Alec Burleson, who spent more time pitching than hitting in the shortened 2020 college season. If the next great lefty/lefty first baseman is out there, he's probably not even on our radar yet.

Last year, for example, the Giants chose lefty hitters with each of their top four picks. Three of them threw right-handed.

Back in 2010, the Pittsburgh Tribune touched on the topic. Upon being told that only a third of teams that year had a lefty-fielding first baseman, then-Pirates first baseman Adam LaRoche offered, "I think that¡¯s coincidence. Five years from now, it¡¯ll be back up to 80 percent."

That hasn't happened, obviously. It might never happen again. The golden age of the lefty/lefty player, especially at first base, seems to be long gone.