The long, weird history of the eephus pitch

Bob Tewksbury remembers the day well.

Mark McGwire had arrived in Minnesota in the midst of his record-smashing 1998 campaign with the Cardinals. He had hit 36 home runs in just 73 games, including a monstrous shot off Twins pitcher Mike Trombley the night before.

The 37-year-old Tewksbury, on the other hand, was in the swan song of a very good 13-year MLB career. He had a curve and a fastball that generally stayed in the mid-to-upper 80s -- maybe 90 mph on a good day. But ... he also had another pitch.

[A version of this story originally ran in August 2020].

A kind of secret weapon he had developed in the mid-1990s and pulled out only when the timing was right. What some would call a junk pitch. An ultra-slow curve that came floating in to hitters at a cartoonish 50 mph.

"I remember I did it in San Diego in '96," Tewksbury told MLB.com over the phone. "I threw it to Willie McGee and he wouldn't talk to me for the next three days."

Tewksbury thought the pitch might also work against a power hitter like McGwire, who feasted on fastballs. But he would only throw it to him if he got the first two batters out in front of him. He told teammates of his plan, and they were more than excited when the time came in the top of the first.

"I get the first two guys out and there's this thunderous noise of footsteps coming from the clubhouse down to the field to watch me throw this pitch," Tewksbury remembers. "I could hear it on the mound."

The Twins' soft-throwing starter followed through on his promise -- baffling one of baseball's most monstrous home run hitters in the prime of his career, not once, but twice with -- as his son called it -- "The Dominator." The slowest pitch a pitcher can pitch: the eephus.

-------------

The eephus' origins go far back in baseball time and can maybe best be understood from the Hebrew origins of the word. It translates to "nothing."

Of course, it's been called other names, too. The balloon ball, the Monty Brewster, the rainbow curve, the Bugs Bunny curve, the Super Changeup, the Soap Bubble (Vicente Padilla), the Fossum Flip (Casey Fossum), the McBean Ball (Al McBean), the Folly Floater (Steve Hamilton).

Whatever the name, they're usually all the same -- a slow, high-arcing pitch, generally in the 45-55-mph range, brought out to surprise the batter looking for a 95-mph fastball and leave him thinking, "What in the hell just happened?"

Tewksbury, like many others who practiced the pitch, adapted it on his own. It was something to add to his repertoire and make his fastball seem faster than it might've been. But Rip Sewell, the man who made the eephus famous, was actually forced into throwing it to save his career.

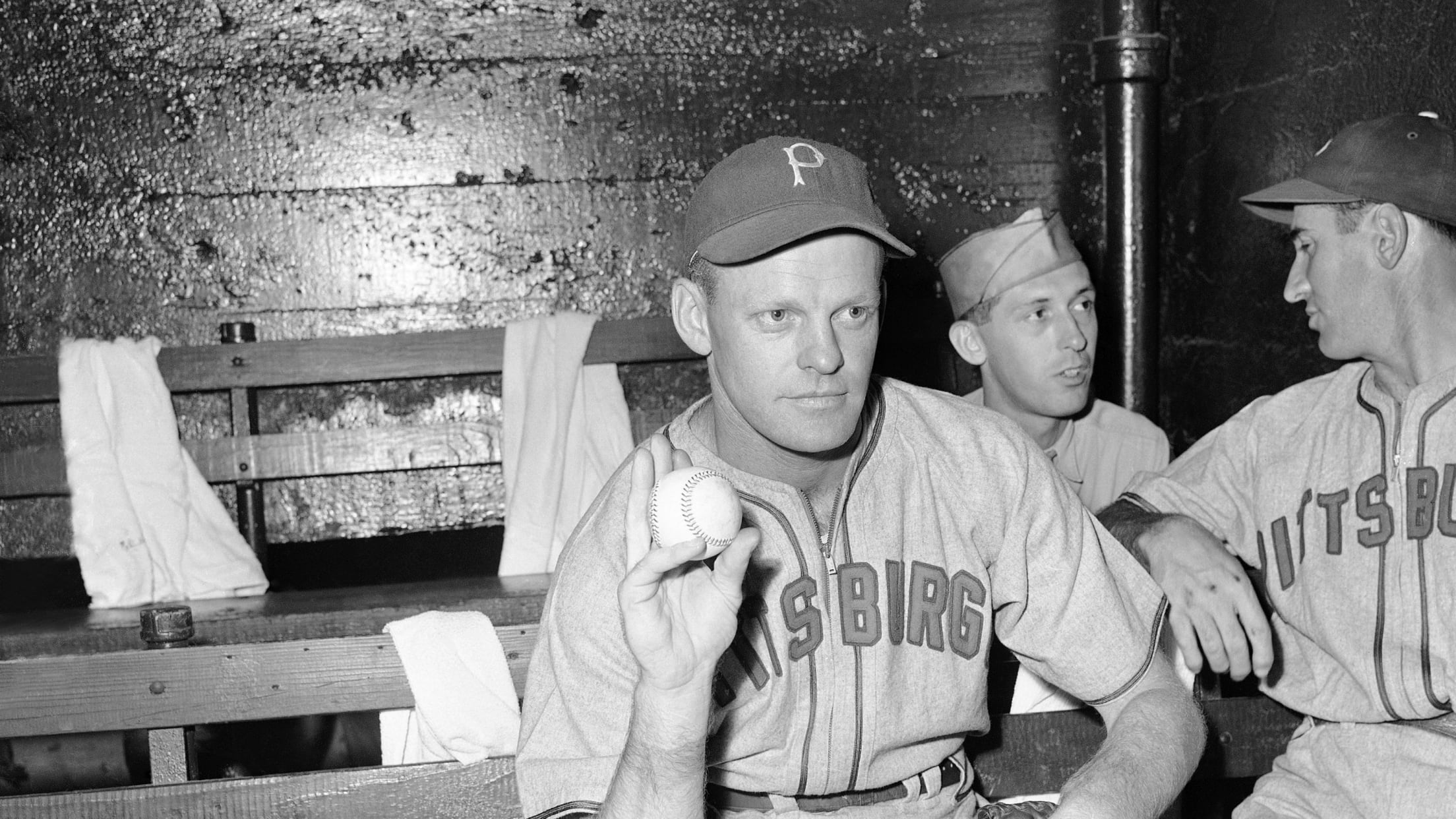

After spending years and years in the Minor Leagues, Sewell caught on with the Pirates at the age of 31 and did well from 1938-'41 -- a 40-32 record, 3.58 ERA and MVP votes in the 1940 season. But then, in the winter of 1941, he shot himself in the foot during a hunting outing. Sewell couldn't push off the mound with his right toe like he used to, and his fastball and curve suffered for it. So, he ended up developing a new pitch to counteract his troubles: a 25-foot high, back-spinning slow-ball. He would hold onto the seam and then flip it toward home plate with three fingers. Bill Phillips, a 19th-century pitcher, was likely the only other to ever throw something like it. But that was 40 years before; Sewell had brought the eephus into the Modern Era.

Pittsburgh's hurler described how batter Dick Wakefield reacted when he first saw the pitch during an exhibition matchup in 1942.

"He started to swing, he stopped, he started again, he stopped, and then he swung and missed it by a mile. I thought everybody was going to fall off the bench, they were laughing so hard."

It maybe looked a little something like this.

After the game, Sewell's teammate Maurice Van Robays was the first to coin the pitch an "eephus." Reporters asked what that meant and he said, "Eephus ain't nothin, and that's a nothing pitch." (Efes is actually how it's spelled in Hebrew.)

That nothing pitch resurrected Sewell's career, and from his age-35 season in 1942 to his age-42 in 1949, he'd never been better. He went 103-65 with a 3.36 ERA, including back-to-back 21-win seasons in '43 and '44. Some hitters caught it and fired it back at him, while others wondered if it was even legal. Sewell was also an All-Star three times during that stretch and tried out the toss against Ted Williams during one of those Midsummer Classics. It did not go well.

Although nobody used it as often as Sewell, many pitchers added the eephus to their arsenal post-1950. Some to great success, others not so much.

Orlando "El Duque" Hernandez used it one too many times against Alex Rodriguez in 2002, admitting postgame, "It's possible it was a mistake."

It's possible it was a mistake

Bill Lee had an eephus, because of course he did. He called it the "space ball" or the "Leephus" and was even bold enough to bring it out during a World Series Game 7 in 1975. The Red Sox were up, 3-0, but not for long. They'd end up losing the game and the Series, continuing their long Fall Classic drought.

47-year-old Phil Niekro used it once when he was experiencing chest pains on the mound and didn't have the energy to throw anything else. Mixed in with a knuckle-curve, it generally worked out pretty well for him.

Satchel Paige had an eephus that left batters crumbling to the ground, begging for mercy. We're just not sure whether that was the one he called the "Whipsy-Dipsy-Do" or "Wobbly Ball" or one of the other hundreds of named pitches he had.

Besides Tewksbury's battle with McGwire, one of the other more famous incidents of the eephus caught on tape has to be Dave LaRoche's LaLob to Gorman Thomas in 1981.

LaRoche developed his lob on a dare and used it to great success and fanfare when he pitched for the Yankees in the early-80s. The two-time All-Star kept flipping it "a little slower and higher" until he got it to a ridiculous 28 mph. And during a game at Yankee Stadium, LaRoche used his floater three straight times against power-hitting Brewers outfielder Gorman Thomas -- two of them for strikes. Would he do it a fourth time to try and get the strikeout? To the crowd's delight and Gorman's helmet-smashing disgust, he did. The result is one of the best baseball clips you'll ever see.

Robin [Ventura] came up ... and told Steinbach, 'Tewks may need security to go to his car tonight because Albert wants to kill him.'

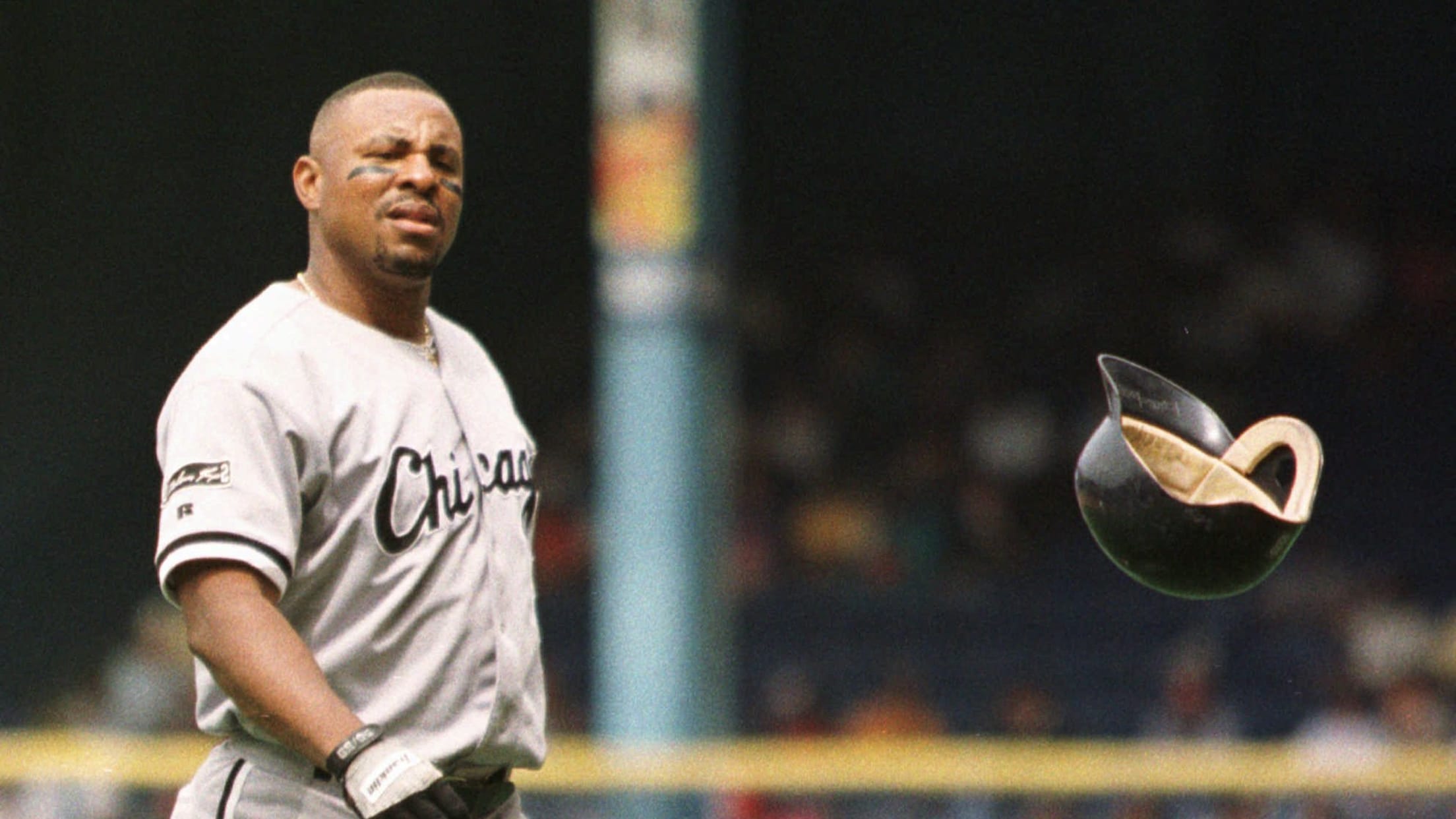

Somebody maybe more mad than Thomas in '81 was the notoriously short-tempered Albert Belle when he faced Tewksbury in 1997. There doesn't seem to be any video of the exchange, but please, if you find any, send our way.

Belle knew of Tewksbury's eephus from previous meetings, and as Twins catcher Terry Steinbach recalls, the White Sox slugger was actually practicing the timing of the pitch in the batting cages before the game.

"During the pitcher and catcher meeting before the game, I said, 'Tewks, Albert's over there sittin' on your eephus pitch,¡¯" Steinbach recalled to MLB.com. "And Tewks said, 'What?'"

Tewksbury decided to use his fastball in the first two at-bats against Belle, but then in the third and final time, with a 3-1 count and a man on first, it was time to break out the "two-finger wiggle."

"I threw him an eephus curveball ... and he swung so hard that he jammed himself and he hit a little pop up to [second]," Tewksbury says. "Albert went into the dugout and was staring me down. Robin [Ventura] came up ... and told Steinbach, 'Tewks may need security to go to his car tonight because Albert wants to kill him.'"

It was a much different reaction than McGwire's, who sent Tewksbury a note after the game saying "he's a sucker for that kind of stuff and he would've swung at it all day."

"Bob was upper 80s, sometimes he'd hit 90," Steinbach says. "But to be able to throw a 50-mph breaking ball without tipping it off, without slowing your windup down, it's hard to do. And he did it very well. ... It's a great pitch to put in the back of great hitters' minds."

Present-day stars have carried on the eephus tradition, throwing their parachuting floaters when hitters least expect it. Yu Darvish always has it in his back pocket, Clayton Kershaw uses it sparingly and Zack Greinke has used it multiple times later in his career. Take the 53.5-mph curve he lobbed in August 2020 -- getting a strike and laugh from batter Trent Grisham.

You have to think that Rip Sewell, who started throwing the eephus because he accidentally shot himself in the foot, would find the continued and consistent use of his joke pitch pretty comical.

A pitch that literally means nothing turned into a whole lot of something.