Ohtani might just be a real-life superhero?

In the span of six days in an otherwise unremarkable mid-June week in the middle of yet another otherwise unremarkable Angels season, the entire Shohei Ohtani Experience was put on full display.

On Tuesday, June 15, he homered in a 6-4 loss to Oakland. On Wednesday, he had two hits (including another homer) and a stolen base. Thursday brought a starting pitching appearance, where he threw six one-run innings against Detroit and drew two walks while hitting second in the lineup. (He tossed in an athletic fielding play for good measure.)

Friday, back at DH, he homered twice, hours after he announced he¡¯d participate in the T-Mobile Home Run Derby. Saturday brought a homer. It was the first time in 100 years anyone had hit five homers and picked up a win within a week. As an exclamation point, the next day, Sunday, June 20, he homered again.

On the seventh day, he rested ... but only because the Angels didn¡¯t have a game scheduled. (He celebrated by winning the AL Player of the Week award, his third.)

This -- all of it, the laser beam homers, the blazing fastball, the dominant splitter, the shockingly good foot speed, every night, all at the same time, the overall all of it of it all -- might start to feel like it¡¯s becoming normal, as though it's normal to be on a 60-homer pace at the same time he's striking out a third of the batters he faces on the mound, as though it's normal to be selected to the All-Star Game separately as a pitcher and a batter, where he'll pull double duty the night after showing off his power in the Home Run Derby.

It is, we can confirm, not normal. We need to talk about how not-normal this all is.

"I've been doing this 26 years, seen as many players as anybody, but I've never seen a skill set like this," an international scouting director told MLB.com¡¯s Jonathan Mayo in 2017, before Ohtani had selected the Angels. ¡°There should be giddiness. No one has ever seen it.¡±

If it feels sometimes that we¡¯re drowning in Ohtani adoration, that we¡¯re talking too much about a player on a fourth-place team that hasn¡¯t been to the playoffs since 2014, that¡¯s understood, and possibly not quite wrong. But at the same time, it simultaneously seems like we¡¯re not talking about this enough. No one has ever done this before, not like this. The Ohtani we were promised in December 2017, the one who was coming to North America as perhaps history¡¯s most impossibly overhyped baseball player, has arrived, fully formed.

Not that there weren¡¯t flashes of it before, of course. The hype began five years ago, if you were only interested in knowing when Ohtani would come to the States, or earlier than that if you were following Japanese baseball. The sweepstakes to sign him, before he selected the Angels, was something of a circus, where we were all desperately trying to dig up any video, reports, or data we could find to validate the excitement.

When he arrived at that first Spring Training, he was welcomed by standards of excellence he could not possibly meet, given that the expectation was merely ¡°do something not seen in a century, in a new league, in a new country.¡±

The ask was, to put it simply: Do the impossible. And do it well. Immediately.

He didn¡¯t. Not right away, not when there was an entire Spring Training of now-regrettable ¡°will he even be able to compete?¡± worries. Once the 2018 season began, he hit well and pitched enough to win the American League Rookie of the Year Award, and a week into the season, we noted how loud all of his skills seemed to be. Even if he was still more of a ¡°DH who pitched sometimes¡± than a true ¡°two-way player,¡± given that he never did both in the same game that year, it still looked like confirmation of the hype.

At first, anyway. After injuring his elbow in June, he underwent Tommy John surgery, keeping him off the mound for the entire 2019 season, during which Ohtani's hitting suffered as he battled through a sore knee that eventually required surgery of its own. 2020 was appropriately enough an all-around disaster; he posted a mere 76 OPS+ and made it on the mound just twice due to a flexor strain.

As the baseball world started to ask questions about whether it might be best for Ohtani to just focus on hitting, manager Joe Maddon said that for 2021, a fully-healthy Ohtani was ¡°full-go.¡± For his part, Ohtani noted that he¡¯d changed his offseason workouts and diet; it was later reported he¡¯d visited data-driven pitching factory Driveline Baseball. You¡¯ve seen what¡¯s happened since.

The Ohtani story is one that by its very nature transcends mere numbers, because while his ability to throw hard and hit hard and run fast and do it all at the same time is unprecedented -- as we will go into great detail about, obviously -- that doesn¡¯t fully tell the story about what this all means. If someone, in the future, comes close to what Ohtani is doing now, they won¡¯t be the first.

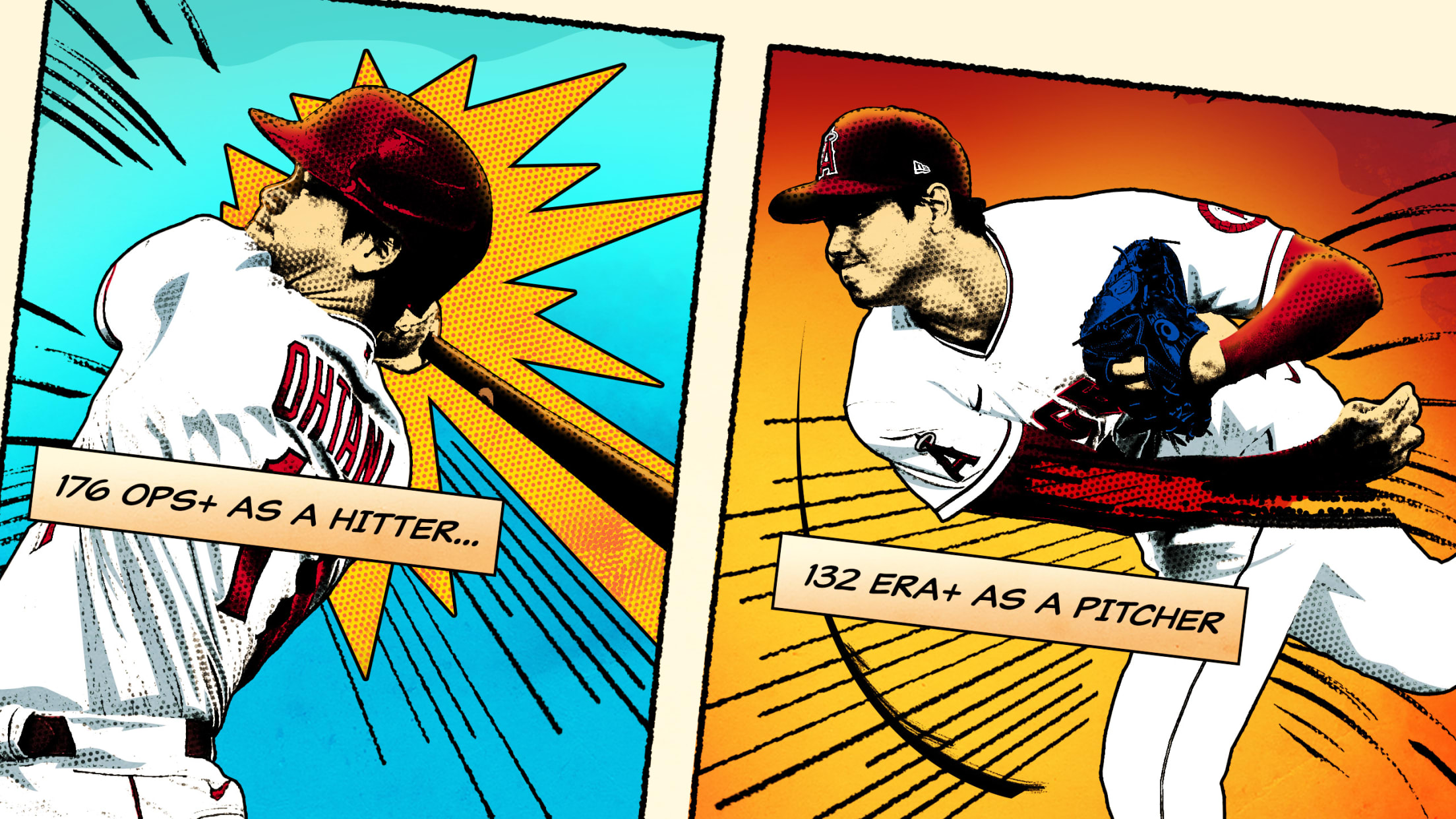

Ohtani has a 176 OPS+ while hitting. It's the third-best in baseball, behind only Fernando Tatis Jr. and Vladimir Guerrero Jr., two elite young sons of Major League stars. He has a 32.3% strikeout rate while pitching. It's the 12th-best in baseball, better than Yu Darvish or Clayton Kershaw or most anyone else. Setting aside any worries about whether the two-way role would limit his availability, the Angels have played 85 games, and Ohtani has appeared in 80 of them.

Imagine, if you will, a batter more successful than Aaron Judge, a pitcher allowing fewer hits per plate appearance than Max Scherzer or Carlos Rod¨®n, and a runner faster than Trevor Story, and then remember you need not imagine, because that¡¯s Ohtani. He is here. He is doing it now. Nightly.

Growing up, Ohtani reportedly read comic books about Goro Shigeno, a fictional Japanese youth who hit and pitched and grew up to play for the pro team in Anaheim. As an adult, that's exactly who Ohtani has become -- a larger than life character.

Or, perhaps, as Mets starter Marcus Stroman tweeted: ¡°Ohtani is a mythical legend in human form.¡±

That's praise that's simultaneously well-deserved and entirely too much, as there's risk in letting the awe of all of this overtake the fact that when he's not piling up endless achievements on the field, he's still a person, a man who reportedly likes naps and baths and movies just like the rest of us. For all the numbers we're about to throw at you, all the historical context, there's little more powerful than hearing the way his fans speak about him. "As a Japanese Canadian," a fan told the Toronto Star earlier this year, "it¡¯s freaking amazing that you have someone like Shohei Ohtani doing things like that.¡±

It absolutely is. It is, we agree with great gusto, freaking amazing.

All stats entering July 7. Yes, he's already homered again. He cannot be stopped.

Better than the Babe

It is impossible to look at any of the things that Ohtani is doing on either side of the ball without pointing out that he is doing them all, together, simultaneously. The most obvious comparison is to Babe Ruth, history¡¯s most legendary two-way player and probably just the most famous player ever in general.

So let¡¯s go ahead and compare him to Ruth ... except, Ruth didn¡¯t do this, not really, at least for long.

In his first four years with the Red Sox (1914-17), the Babe was exclusively a pitcher or pinch-hitter. In the final 16 years of his career (1920-35), spanning the entirety of his time with the Yankees and the oft-forgotten final year as a Brave, he appeared on the mound only four times. It was only in 1918 (71 games in the field and 20 on the mound) and ¡®19 (112 games in the field and 17 on the mound), his last two years with Boston, where he really did both.

But while Ohtani is pitching regularly, once every five or six days, and hitting in between, Ruth rarely did that. In 1918, he was again exclusively a pitcher or pinch-hitter for the first month of the season; once he got into the starting lineup as a hitter for the first time in early May, he¡¯d often go weeks at a time without pitching. (¡°Babe, enjoying the notoriety his hitting was generating, often feigned exhaustion or a sore arm to avoid the mound,¡± reports his SABR bio, though he did keep a more Ohtani-like schedule in August.)

In 1919, Ruth¡¯s mound appearances were mostly devoid of consistency; in the final 55 games he played, he pitched only four times. Sent to the Yankees after the season, his pitching career was mostly finished before he turned 25.

Still, because of the Great Bambino¡¯s fame, you can start with this: Before Ohtani came along, only one AL or NL player had ever had a season with at least 15 homers hit and 10 games started as a pitcher. That was Ruth in 1919. Ohtani did it in 2018. Now he¡¯s done it again in 2021. When he reached 30 homers earlier this month, he was the first hitter to get there in 2021, and the first player ever, Ruth included, to do it in a year where he started at least 15 games as a pitcher.

In the century-plus since Ruth¡¯s 1919, only four players have started a dozen games both on the mound and elsewhere in the lineup, as Ohtani has this year, and two of them did it the same year as Ruth first did, 1918. (We¡¯re excluding Earl Weaver¡¯s 1980 shenanigans with Cy Young winner Steve Stone, who ¡°started¡± 12 late-season games at DH without ever coming to the plate, a stunt that precipitated a rule change.)

The most recent, two-time All-Star Wes Ferrell, was an excellent hitter for a moundsman; he actually still holds the all-time record for most home runs hit as a pitcher, with 38. (Ohtani has just one so far, coming on April 4 of this year.) Ferrell, however, started only 13 career games away from the mound, all coming in the final weeks of 1933 while a sore shoulder prevented him from pitching.

It hardly feels the same. Meanwhile, the ¡°first since¡± facts keep piling up.

On April 4, on national TV for ESPN¡¯s ¡°Sunday Night Baseball,¡± Ohtani hit second in the lineup while starting on the mound, the first in the AL or NL to do that since Jack Dunleavy of the 1903 Cardinals. That game also marked the first time since 1976 that an American League team intentionally chose to bypass the designated hitter. (Tampa Bay, by mistake, had done so in 2009.) On June 30 in New York, he hit leadoff while pitching, the first to do so in over half a century -- and the last time it had been done, back in 1968, it was part of a "playing all nine positions in one game" stunt.

On April 27, Ohtani became the first AL or NL player since Ruth in 1921 to start a game on the mound while also leading the AL or NL in home runs as a hitter, a feat he¡¯s repeated several times since, including his last several starts. (Ruth finished that game in center field, and would not appear on the mound again for more than nine years, as a stunt in 1930¡¯s final game.)

On May 12, Maddon penciled in Ohtani to lead off against Houston the day after he¡¯d been the starting pitcher, a sequence that hadn¡¯t been seen since 1916.

When he stole his 10th base on June 16, it marked only the eighth time in AL or NL history that a player swiped 10 bags in the same season they pitched at least 10 times, but two of those are Ohtani himself (he¡¯d done it in 2018 as well) and five of the other times, aside from George Sisler in 1915, came in the first three years of the 1900s. By reaching 30 homers and 10 steals through the halfway point of the season, he became the first to do it in American League history, and just the third overall.

Four days later, his home run off Casey Mize, the 70th of his career, made him just the fourth player in AL or NL history to have that many homers in a career that also included 100 pitching strikeouts, along with Ruth, Rick Ankiel, and Johnny Lindell. Ankiel and Lindell were not ¡°two-way players¡± like Ohtani; Ankiel famously converted from the mound to the outfield, and Lindell was a pitcher at the start and end of his career, sandwiched around a decade as an outfielder.

It feels like a lot of people are talking about Shohei Ohtani, but still nowhere near enough people are talking about Shohei Ohtani. What he¡¯s doing in baseball is insane.

NFL star J.J. Watt

On June 23, Ohtani pitched against the Giants at home in Anaheim, taking his usual second spot in the order as the team bypassed the designated hitter. But since San Francisco did take the rare opportunity to use the DH in an AL park, it made it the first time in Major League history that we saw a National League team deploy the DH in a game against an American League team that did not, which is quite the concept to wrap your head around.

And, since he leads the Angels in home runs (31) and, with 87 pitching strikeouts, is only two behind Andrew Heaney's team lead of 89, there's this: If he finishes the season topping the club in both areas, it will be the first time a player has done that since Walter Johnson in 1918 -- and the first time anyone¡¯s done it hitting more than a mere three homers.

(The Negro Leagues, it should be noted, also had several accomplished two-way players, some of whom may have also matched or even exceeded these feats. As the process of officially integrating those stats continues, names like Bullet Rogan, Mart¨ªn Dihigo, and Goose Curry will receive greater and long overdue recognition, and improved statistical research methods may allow for some of these specific feats to include their achievements, as well.)

On and on and on it goes like this. Every single time Ohtani does anything, it seems, there's a note to point out that it's been decades or centuries since anyone's done the same. And if it really was that long ago for some of these feats, if it hadn't been done since 1935 or 1905 or 1885, then it came in an entirely different sport.

The Bat

We promised, above, that the Ohtani story transcends mere numbers. It does. It must. But the numbers tell the story too, the ones that express the pure raw skills. They can be as simple as this:

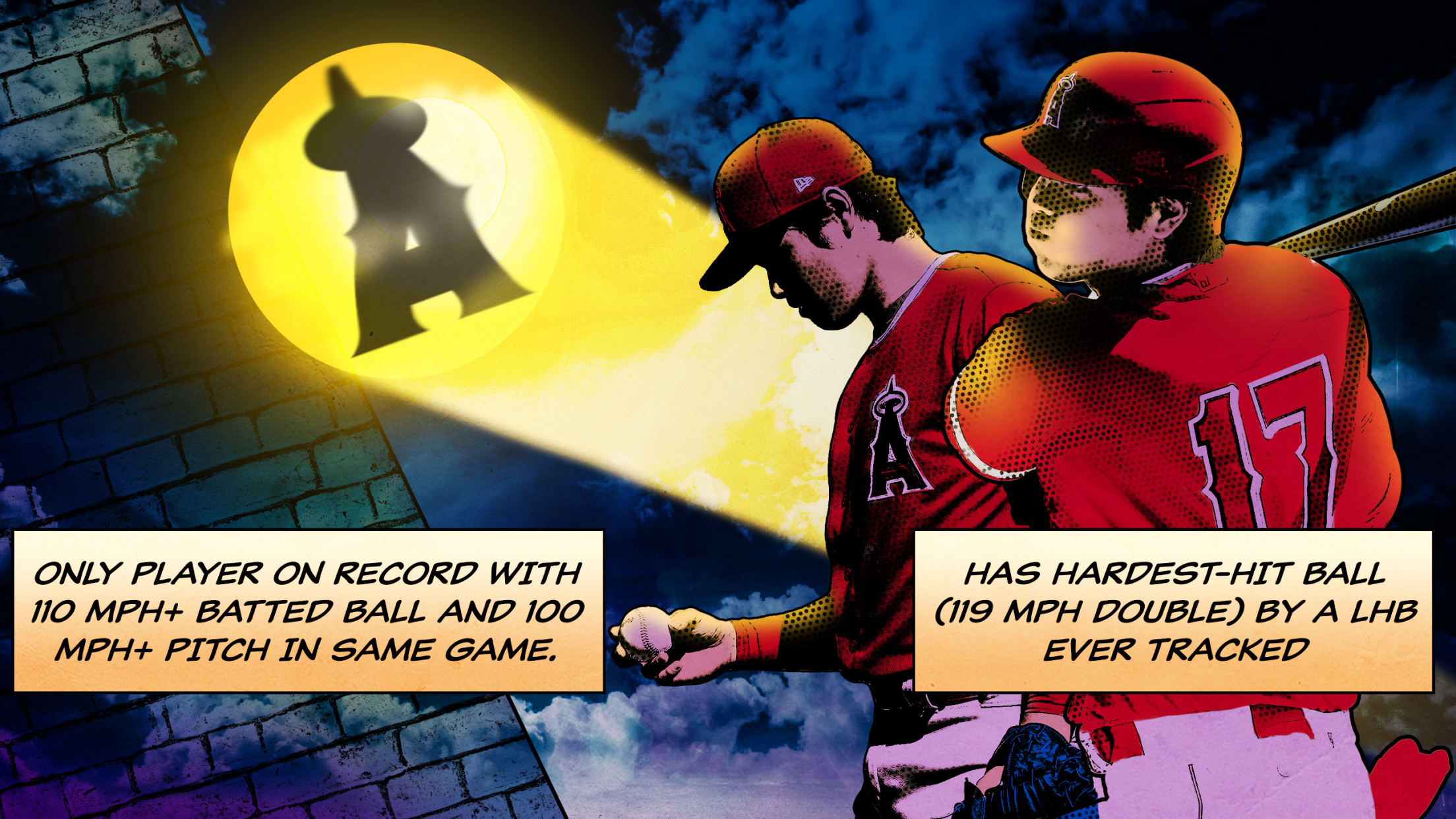

No left-handed batter has ever hit a ball as hard as Ohtani has, as far as we know.

Sit with that one for a moment. Let it stay with you. When Ohtani laced a double in Kansas City on April 12 at 119 mph, it was the hardest-hit ball ever tracked by a left-handed hitter. Now, there¡¯s an obvious caveat there, which is that ¡°ever,¡± in this case, only goes back to 2015, when Statcast tracking first came online. We really don¡¯t know how hard Barry Bonds hit it, or Ted Williams, or Jim Thome, or Ken Griffey Jr., or Ruth himself. We never will.

But what we do know is that there are limits to how hard a human being can hit a ball in a game setting, because Giancarlo Stanton keeps showing us.

The ball comes off his bat like no one I've ever seen.

Ohtani's teammate and fellow All-Star, Jared Walsh

Stanton, despite his myriad injuries over the last few seasons, owns the hardest hit ball of every single season, including this one, and his maximum has consistently been around 121 mph. So, is it possible Ruth or Williams or some other lefty legend hit a ball harder than Ohtani? Sure. But based on everything we know about the increasing strength, size and power of players over the years, even if they did, it wouldn¡¯t be by much. There¡¯s only so much ceiling above 119. There's at least a chance Ohtani stands alone in history here.

On April 4, when Ohtani hit this tank off Dylan Cease that sure sounded like it was the hardest-hit ball of all time (it was a comparatively modest 115 mph) ¡

¡ it was easy to forget that it came mere moments after he'd hit 100 mph as a pitcher three times in the first inning, and moments ahead of him doing it twice more in the second.

He is, at the moment, tied for the best hard-hit rate in baseball (57%), which is another way of saying "no one hits it harder more often." If he keeps it up, it¡¯d be the fourth-best seasonal mark on record. If you¡¯re down with barrels -- the Statcast metric that quantifies the perfect combinations of exit velocity and launch angle, i.e., ¡°the only thing better than hitting the ball hard is hitting it hard in the air,¡± then no one, not Judge or Stanton or Ronald Acu?a Jr. or Vladimir Guerrero Jr. or anyone, has their plate appearances end in a barrel more often.

When he puts the ball in the air, absolutely no one hits it harder, averaging over 101 mph.

"Once you see him in person,¡± said Angels teammate Jared Walsh, ¡°I mean, the ball comes off his bat like no one I've ever seen."

Walsh isn¡¯t wrong. Only four hitters have hit at least seven balls at 115 mph or more this year, with Ohtani being joined by Stanton, Judge and Guerrero. That 119 mph double made Ohtani one of only five players since 2015 to hit even a single ball that hard, and none of them were pitchers. He set the Angels record for hardest-hit home run on May 25, and then topped himself on June 28.

It¡¯s because of that that it¡¯s not nearly enough to point out that Ohtani is one of only five starting pitchers to touch 100 mph at least nine times this year (he is) or that Jacob deGrom and Gerrit Cole are the only starters to throw a pitch harder than the 101.1 mph he touched on April 4 (they are). It¡¯s more necessary to look at the players who have done both of these things at the same time, because there aren¡¯t many.

For example, the complete list of players since 2015 to throw a ball 100 mph+ and hit a ball 110 mph+ in the same game is a brief one: Ohtani stands alone.

Mr. Do-It-All

Now, it¡¯s one thing to merely appear as a pitcher and a hitter, and another thing to display some truly impressive skills while doing it. It¡¯s another thing, entirely, to excel at them.

Ohtani, the hitter, leads the Majors in extra base hits with 53. He¡¯s got that 176 OPS+, which is to say that he¡¯s been 76% better than the league-average hitter, with some big time names in his rearview mirror, like Acu?a, Judge, and Xander Bogaerts. If he keeps that up, it¡¯ll be the best hitting season by anyone not named Mike Trout in Angels history, and Trout is probably going to end up as the best player who ever lived.

When he reached 23 homers, it was faster than any Angel had ever reached that point, and it¡¯s not like between Trout, Vladimir Guerrero Sr., Troy Glaus, and Tim Salmon that the team has lacked for sluggers over the years. In June, Ohtani's 1.312 OPS was the second-best hitting month by an Angel (minimum 20 games) in club history, behind a Trout month from 2015 -- and he did it while allowing six earned runs in his first four starts, before a poor outing in the Bronx on the final day of the month ruined his numbers.

At times, it seems like there¡¯s not a place you can put the ball that he can¡¯t do something with it.

When he took Cleveland lefty Sam Hentges deep on May 17, it was off a pitch well above the strike zone; it was, at 4.2 feet above the ground, the second-highest pitch anyone has taken deep this year. Five days later, he doubled off Oakland¡¯s Chris Bassitt on a pitch that looked like it might well hit him; only once in baseball this year had anyone else had an extra base hit on a pitch further into the left-handed batter¡¯s box. He¡¯s doubled off a pitch in the right-handed batter¡¯s box, too.

Just look at these.

Meanwhile, Ohtani, the pitcher, has that Top 10 strikeout rate, ahead of Joe Musgrove, Robbie Ray, and Brandon Woodruff, men who are paid well to pitch full-time. If you get to two strikes, well, don¡¯t -- only deGrom, having possibly the most dominant season of all time, along with Kevin Gausman, Glasnow, and Freddy Peralta, provides worse outcomes for batters.

But more impressively, perhaps, is that there are signs he¡¯s still getting better. If there was a concern about the early part of his 2021, it was that he wasn¡¯t terribly effective at throwing strikes. Ohtani walked five in his first start, then, after a brief absence from the mound while dealing with a blister, returned to walk six Rangers on April 20. Two starts later, he walked six more. He had, through May 10, the absolute highest walk rate in the game (22.6%) of anyone who had thrown as many innings as he had. It was a problem.

And then: It wasn't. Ohtani walked only one Astro on May 11, and just two against Cleveland after that. There have been blips -- that June 30 debacle in New York, certainly -- but he turned that 22.6% walk rate through May 10 into a mere 9.2% walk rate ever since.

Put another way, he walked 19 in his first four starts ... and just 16 over his next nine, including the fact that his July 6 start against the Red Sox featured the highest percentage of pitches in the strike zone of any game in his career. "Walking too many batters" was his one weakness, on either side of the ball. It's not that way anymore.

That's not just a big deal in terms of "avoiding walks," though it's of course about that too. When Ohtani gets a swing on a ball in the strike zone, only six pitchers get more swings-and-misses than he does, and two of them are on their way to the Hall of Fame in Max Scherzer and deGrom.

The Unhittable Hurler

It¡¯s not, however, just about the fastball. Ohtani throws five pitches, leading with that four-seamer (53%), often deploying a splitter (19%) and slider (14%), and occasionally showing a cutter (10%) or curveball (4%).

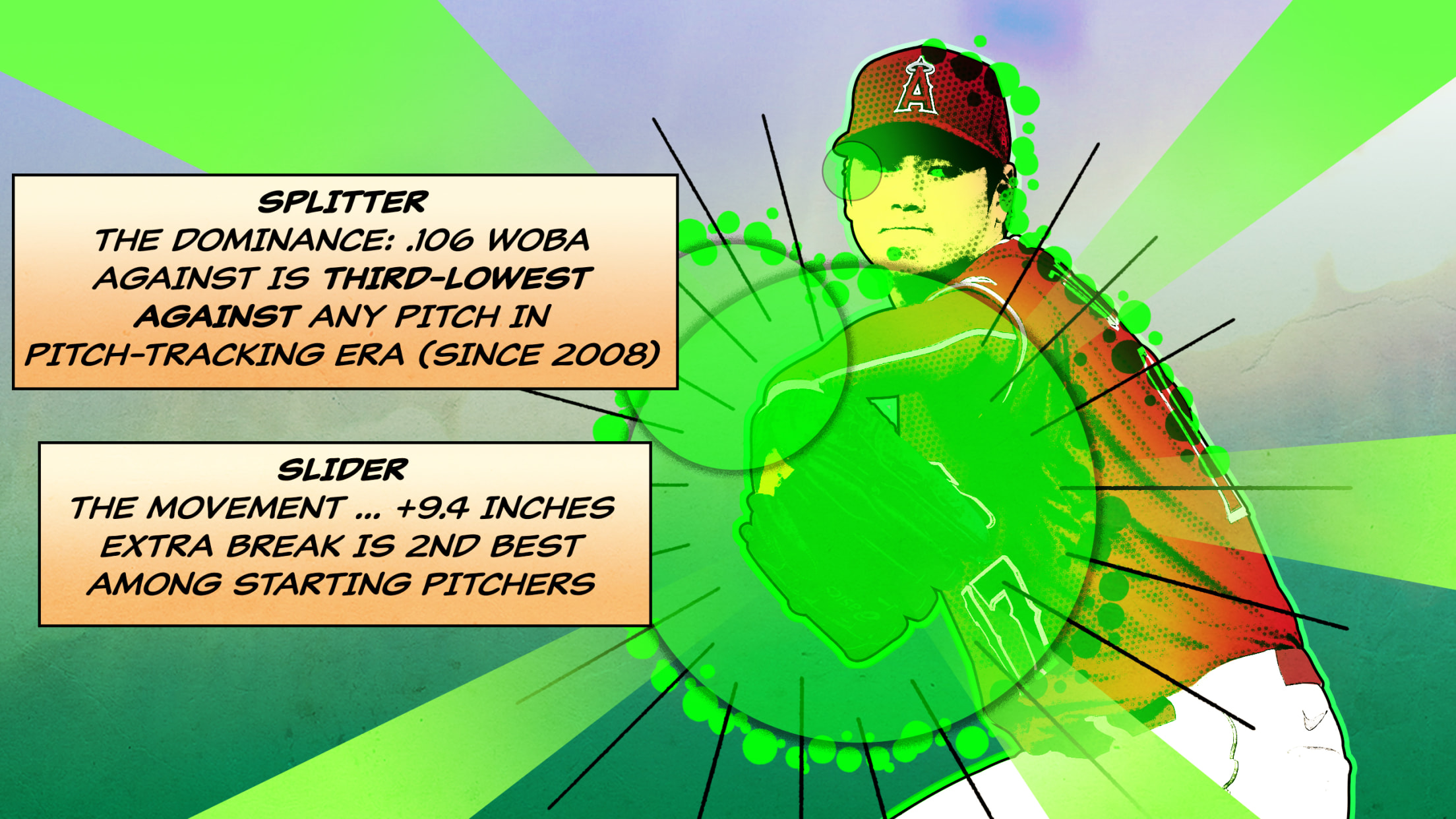

Because of the eye-popping velocity he often shows with the heater, it¡¯s easy to overlook his other pitches. But the four-seamer isn't his most dominating pitch. It¡¯s the splitter.

¡°He¡¯s got one of the special pitches in our game,¡± Seattle manager Scott Servais told the OC Register last month, after Ohtani struck out 10 Mariners. ¡°The Ohtani split-finger, it¡¯s about as good as it gets. When he¡¯s commanding it like he was tonight, it¡¯s a real challenge. It¡¯s as good a pitch as you¡¯re gonna see in the league.¡±

The numbers back it up. In 2018, Ohtani threw the splitter 191 times, allowing a mere two hits. It was, that year, the most dominant pitch in the game, just ahead of sliders from Dellin Betances, Trevor Bauer, Will Smith, Tyler Glasnow, and Blake Snell. In 2021, it¡¯s been more of the same. He¡¯s offered it 196 times, collecting 49 strikeouts and surrendering just six hits, only two for extra bases. He has not yet, in his entire career, allowed a home run on it.

Only four pitches in the sport, among those that have ended 75 plate appearances, have a higher swing-and-miss rate than the 55% mark his splitter posts, and one of those is deGrom¡¯s slider. When a plate appearance ends with a splitter, it¡¯s a strikeout 61% of the time, third-best in baseball to Glasnow's curve.

Put it this way: Since pitch tracking began in 2008, there have been nearly 4,500 combinations of pitcher+pitch type where a hurler has thrown the pitch at least 400 times. The outcomes on Ohtani¡¯s splitter -- the Weighted On-Base Average, if you really want to know -- are the third-best of any pitcher¡¯s pitch type.

Most dominating pitches since 2008

.103 -- Felipe V¨¢zquez slider

.105 -- Jonny Venters slider

.106 -- Ohtani splitter

.116 -- Billy Wagner slider

.123 -- Zack Britton slider

Each of those pitchers, it should be noted, threw lefty. Limiting it just to righties, Ohtani's splitter is the most dominant right-handed pitch we have on record. He¡¯s allowed nine hits on it in his career. One of them looked like this.

But: Why? It¡¯s not that it¡¯s got elite velocity, because while averaging nearly 88 mph on a splitter is nothing to sneeze at, it¡¯s also not something no one else has. It gets a little more drop than average, but not in a way that stands out. It is, instead, because it looks like the four-seamer right up until the exact second it does not -- at which point it drops an additional 19 inches more than the heater does.

¡°If he has command with his fastball, they have no chance laying off of his split,¡± said Hall of Famer John Smoltz, who knows a thing or two about throwing splitters, when speaking to the Los Angeles Times in May. ¡°Because he comes out of the same slot, and it comes out firm in the middle of the zone, it drops and it has great late movement. Trying to catch up with velocity and then distinguish between fastball and split differential, it¡¯s just ridiculous. It comes out of his hand the same way.¡±

If that¡¯s all he had -- the blazing four-seamer and then the diving splitter -- he¡¯d be plenty successful. It¡¯s not. Let¡¯s talk about the slider, the one that has the most horizontal break compared to average of any starting pitcher in baseball this side of Sonny Gray. Put another way, the average slider around his 80.7 mph velocity band breaks around 8 inches. Ohtani¡¯s breaks 17.5 inches.

If not quite as overwhelming as his two big pitches, the slider has made for an effective third weapon; to this point in his career, it¡¯s allowed a mere .163 average.

The Speedster

But you knew about all of that, right? Two-way player. Hits hard. Throws fast. Big homers. Lots of strikeouts. As expected.

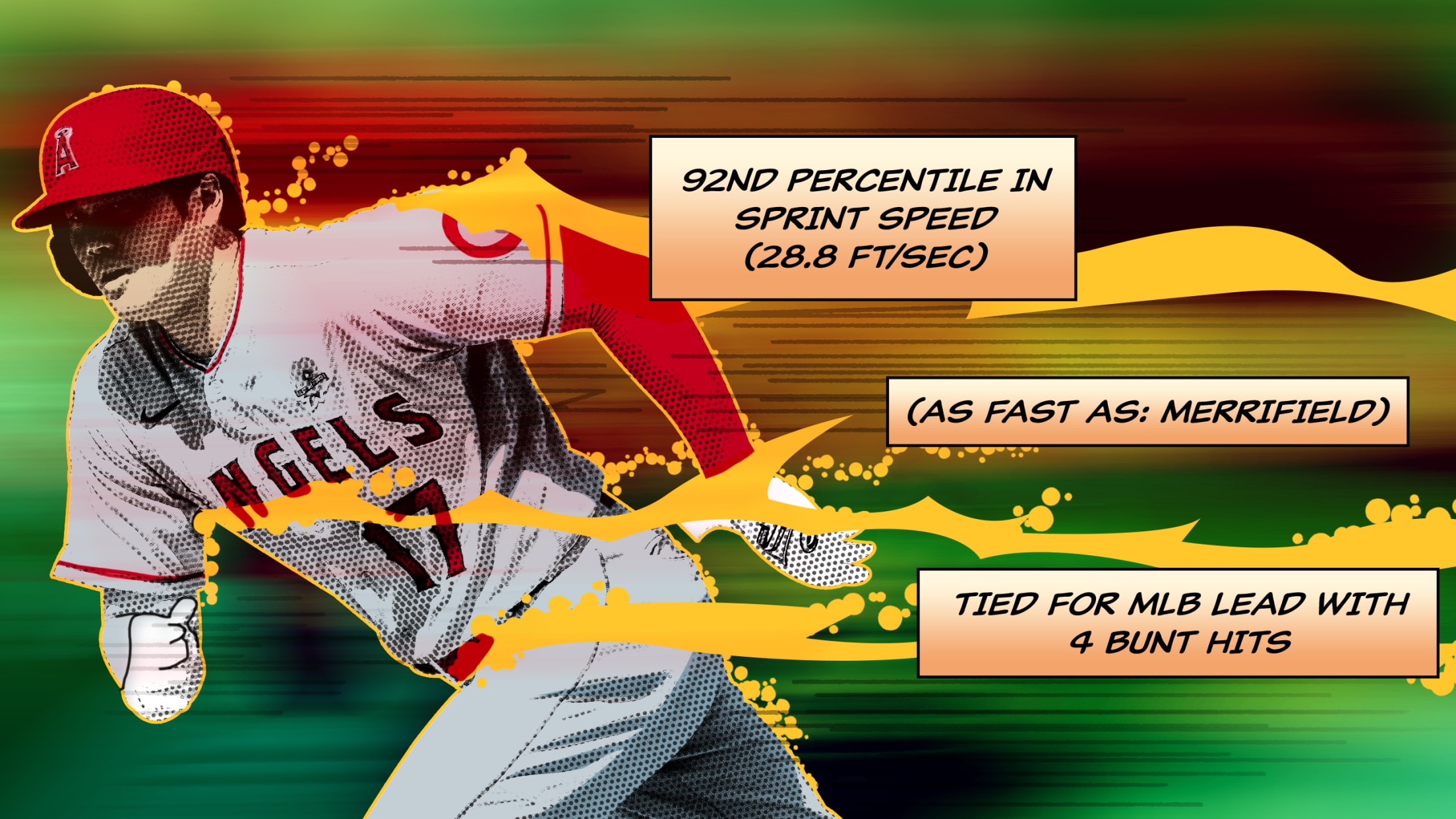

Did you realize, truly realize, how fast Ohtani is?

Did you realize he¡¯s getting faster?

Ohtani, this year, is the third-fastest Angels runner, with his 28.8 ft/sec sprint speed trailing only Trout¡¯s 29.3 and Phil Gosselin's 29.0. Overall, he¡¯s in the 92nd percentile, meaning he¡¯s as fast or faster than 92% of all other runners in the game. You wouldn¡¯t think of him this way, but he¡¯s as fast as Fernando Tatis Jr. He¡¯s faster than Whit Merrifield, or Cedric Mullins, or Ozzie Albies. He¡¯s fast, and that 92nd percentile is up from his 82nd percentile as a rookie.

You can see what it does to fielders. On May 19, Ohtani dropped down a bunt single against Cleveland, one of four he has this year; no one has more, making for yet another leaderboard with Ohtani's name at the top. (That certainly pleased Angels manager Joe Maddon, who has praised Ohtani¡¯s bunting skills; we¡¯d point out that in this game, the Angels were down 3-2 in the sixth inning when he led off, and that¡¯s how the game would end. It's probably better to let him swing.)

On this particular play, Ohtani¡¯s home-to-first time was one of the 10 fastest in baseball so far this year, though the broadcast camera, following the ball, doesn¡¯t really get that point across. Instead, using FieldVision, look at how much faster Ohtani (29.9 ft/sec on the play) was compared to a similar bunt attempt from another lefty -- but one with only league-average speed -- in Jackie Bradley, Jr., who posted a 27.7 ft/sec mark on this April attempt.

That combination of speed and power is, really, somewhat rare. He¡¯s currently one of just four players to have 20 or more homers and 10 or more steals, though that's underselling him a bit since he's the only one with 30 or more homers. He's one of just five players to post 90th percentile or better skills in both hard-hit rate and running speed, and the names here are spectacular. (Trout, if you're wondering, would qualify as well, if he hadn't missed so much time to injury.)

"He flies, man," said former Angels right fielder Kole Calhoun in 2018. That might be an understatement.

The Game Changer

All of this, for a fourth-place Angels team stuck at .500, hovering on the fringes of the race with 18.6% playoff odds at the time of writing, according to FanGraphs.

It¡¯s the same problem Trout has faced for years: How valuable can you be, how much hype can you deserve, when your team never wins? Should Ohtani be a bigger star because of the sheer magnitude of what he¡¯s doing? Or will it always be impossible to break past ¡°fourth place and never on the big stage in October,¡± as has plagued Trout? LeBron James, to choose a superstar from another league, wouldn't have become LeBron James if his teams kept finishing 10th in the Eastern Conference.

The answer, as always, is ¡°it¡¯s a team game,¡± and Los Angeles has had some serious fielding issues this year, as well as the eighth-highest ERA in the years since they last appeared in October. One man, no matter how great, cannot turn a baseball team into a winner.

And yet: All of the numbers we¡¯ve brought up -- the various velocities, the foot speed, the advance, the home runs, all of it -- are context-free, which is to say they look at the thing the player did without worrying about the game situation it came in. You might not be surprised to find out that when we factor that in, it¡¯s yet another thing Ohtani excels at.

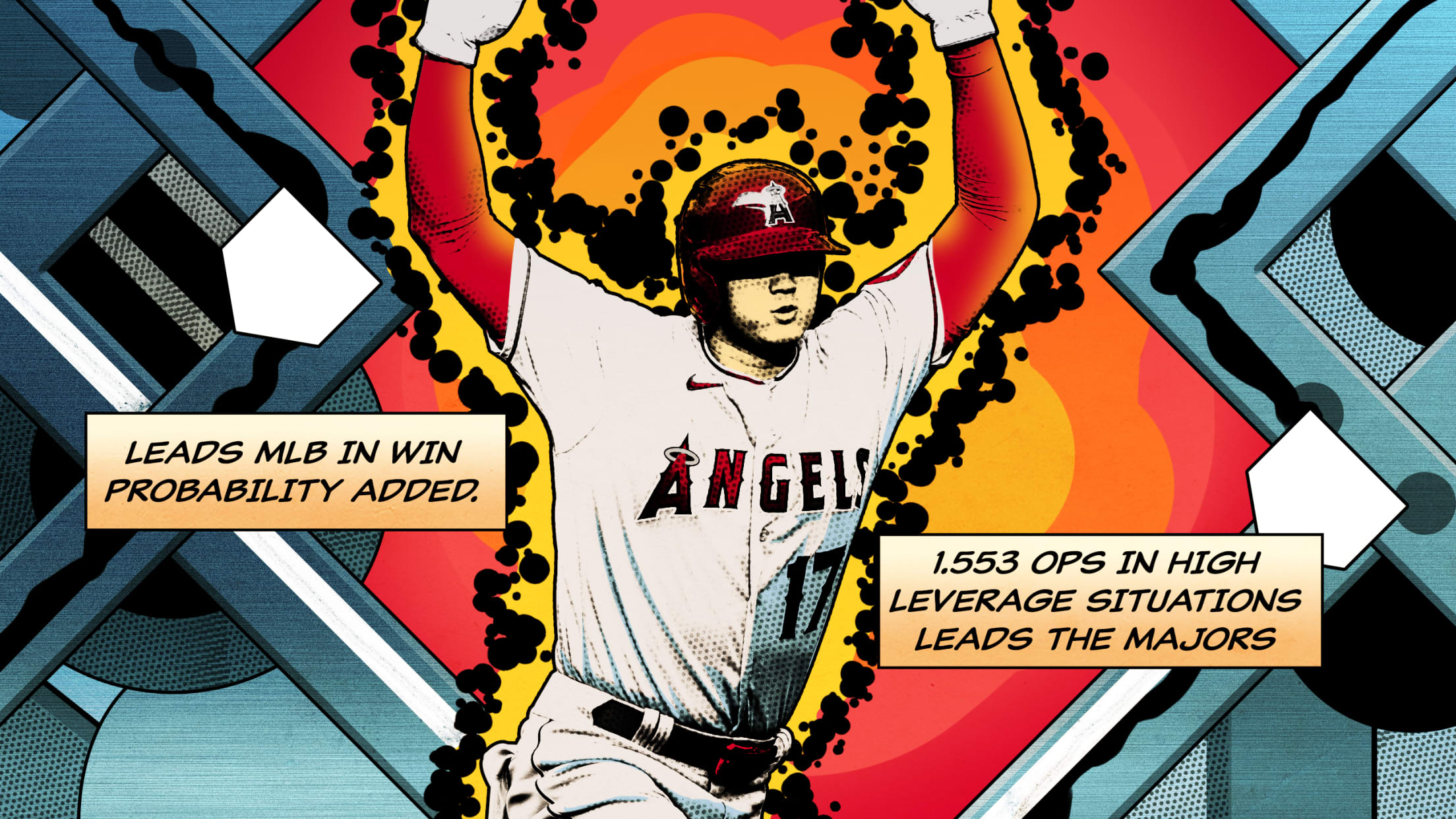

For example, he¡¯s got a .275 average in ¡°low leverage¡± situations and a middling .194 in ¡°medium leverage¡± spots; turn the dial up to ¡°high leverage,¡± and you¡¯ve got a .487/.553/1.000 line. It is the absolute best performance by anyone in baseball in those very important plate appearances. It would be the second-best in the entire Wild Card era behind only Bonds' monstrous 2004 season.

Or consider the idea of ¡°two outs and runners in scoring position,¡± a situation baseball lifers love to point to as the idea of being clutch. As a hitter, Ohtani has a 1.268 OPS with two outs and runners in scoring position; it is the eighth-best among hitters with 30 chances. As a pitcher, in those same spots, he is also ... eighth-best.

Since there are stats for everything, there's a stat for this too. Win Probability Added exists specifically to apply game context to moments, to give more credit for a tiebreaking double in the ninth inning than a solo homer that turns a 10-0 fifth-inning blowout into a mildly larger 11-0 blowout. As a hitter, Ohtani leads the entire sport in context-dependent value, topping Guerrero and Tatis by a decent margin on the WPA leaderboards.

Of course, Ohtani is a lot more than just "a hitter," obviously, and he has added quite a bit of positive high leverage value on the mound, as well; combine the two, and he's lapping the field.

Highest combined Win Probability Added, 2021

4.54 -- Ohtani, LAA

3.94 -- Josh Hader, MIL

3.36 -- Guerrero Jr., TOR

3.29 -- Brandon Woodruff, MIL

3.12 -- Tatis Jr., SD

3.02 -- Zack Wheeler, PHI

The big moments aren¡¯t hard to find. There was the tiebreaking home run in the eighth inning in Houston on April 25. There was the game-tying homer in the fifth inning against Detroit on June 20. There was the full-count, two-out, two-on strikeout of Yo¨¢n Moncada on April 4, even if the Angels defense turned it not only into a disaster but nearly injured Ohtani along with it.

But, more than any other, there was the Fenway Park home run. When he took Matt Barnes deep on May 16, with two outs in the ninth inning, with the Angels down 5-4, with Trout on first, giving the team a 6-5 lead with one swing of the bat, it was the first time the Angels had hit a home run in that situation in nearly eight years; it stands as one of the 10 most valuable moments of the season.

The Angels may not be winning, but there¡¯s very little more Ohtani could do about that.

The Front of the Pack

So: Where does this all lead? Where are we, historically, if this isn't just "a great half-season," and it turns out this is just the first half of what might be an all-time great year?

The immediate question is "will he win the Most Valuable Player Award" if he keeps this up, and the answer right now seems to be that he's going to have an incredibly strong case. No, he isn't hitting quite as well as Guerrero Jr., having a fantastic season in his own right, but also, Guerrero's admittedly-improved defense at first base isn't the same thing as what Ohtani's doing on the mound. (Some voters may dislike awarding the MVP to a player on a losing team; we strongly disagree, and it's not like Toronto is a first-place club anyway.)

He¡¯s the best baseball player I¡¯ve ever seen in my life

CC Sabathia

While MVP voting is rightfully not a simple "compare the WAR" exercise, you can still see how much of a gap Ohtani is going to have here.

2021 AL WAR Leaders (combined pitching+hitting)

5.6 -- Ohtani, LAA

4.4 -- Guerrero Jr., TOR

4.4 -- Marcus Semien, TOR

4.1 -- Kyle Gibson, TEX

4.0 -- Carlos Correa, HOU

But maybe we're not thinking big enough here. What if he keeps this up? What if what we've seen to date is something he can make last all season long? After all, the underlying Statcast metrics show that to this point of the season as a hitter, there's very little that seems like it's more about "good luck" than "great production." What if -- and, we know, an enormous if -- he stays healthy and great on both sides of the ball? Posting a five-WAR season, as he's done, is a great year for 99% of baseball. (In WAR terms, 2 WAR is an average season, and 4 is roughly an All-Star campaign.) Ohtani, however, has done it before the All-Star Game.

To answer that question, we looked back through history. We looked for every AL or NL player since 1901 to have a season with at least 100 plate appearances as a hitter or five games pitched on the mound. This left us with nearly 75,000 player seasons. We took the WAR value for both sides of the ball, combined then, and ranked them.

If Ohtani kept up his current pace, he'd wind up with approximately an 10.6 WAR season. That would be in the top one-half percent of all of these seasons all-time. It would be better than 99% of seasons in the history of Major League Baseball. Of the ones that were better, most of those seasons came in pre-integration era baseball, played against athletes fractionally as talented as today's, almost entirely during the day, rarely if ever requiring the aid of airplanes to travel.

None of those players, not recently, not historically, was a true two-way player. Not even Ruth, who had his best years solely as a hitter.

¡°I personally think he's the most physically gifted baseball player that we've ever seen,¡± Barnes, the Boston closer, said.

¡°He¡¯s the best baseball player I¡¯ve ever seen in my life,¡± said CC Sabathia last year, along with some considerably more colorful descriptions to follow.

Across 19 years in the Majors, Sabathia was teammates with Derek Jeter, Alex Rodriguez, Mariano Rivera, and Thome. He pitched to Ichiro Suzuki, Frank Thomas, Ken Griffey Jr., Chipper Jones, Cal Ripken Jr., and a handful of other Hall of Famers. If anyone would know what greatness looks like, it¡¯s Sabathia.

For all the comparisons to being ¡°the next Babe Ruth,¡± that¡¯s not quite right. Ruth slugged for far longer, in the context of a very different sport, and he single-handedly changed the way the game was played. But he didn¡¯t do this, either, not really. He didn't come to a new country; he didn't face integrated rosters or cross-country flights or endless relievers or the massively more talented opponents that Ohtani sees. Ohtani isn¡¯t the next Ruth. He¡¯s not the next anything.

He¡¯s the first Shohei Ohtani. That's more than enough. It's more than anyone has ever been.