Let's interrupt your regularly scheduled panic over the incredible breakdowns of the Philadelphia bullpen to make a point that shouldn't need to actually be made: Bryce Harper is still really, really good. All-world good, really.

That's a statement that shouldn't at all feel controversial, yet somehow does. Maybe it's because after signing a 13-year, $330 million contract last winter, the Phillies proceeded to finish fourth in the NL East, at 81-81. Maybe it's because a debut season that was impressive by both traditional numbers (35 home runs, 114 RBI) and advanced (128 OPS+, 4.6 FanGraphs WAR) didn't lead to an All-Star Game appearance or a single MVP vote. Maybe it's because "$330 million" sounds like so much money that people expect it to all be earned in a single year, not over more than a decade.

But mostly, we assume, it's because of this: Despite how good Harper was in 2019, and how good he is every year, he didn't come close to matching his 2015 Most Valuable Player season that was legitimately one of the greatest years of all time. He never has. He never does.

That's probably on us. It's probably unfair to be disappointed by a player who is above-average-to-great ever single year. Still, you get why everyone wants to see that kind of season again.

A month into the truncated 2020 season ... what if we are?

In 2015, Harper posted an on-base percentage of .460 and a slugging of .649, good for an OPS of 1.109, and an OPS+ of 198 (where 100 is average.) He won the MVP Award unanimously.

In 2020, Harper has an on-base percentage of .471 and a slugging of .676, good for an OPS of 1.147, and an OPS+ of 209. That's all superior to what he did in 2015, and it is the third best line in baseball, behind Dominic Smith and Jesse Winker.

The difference here is that he's stepped to the plate 86 times this year, and he did this over 521 plate appearances back in 2015, so it's not exactly the same. Still, we can try to see what's different. Here's the first question:

1) Has he ever been this hot before?

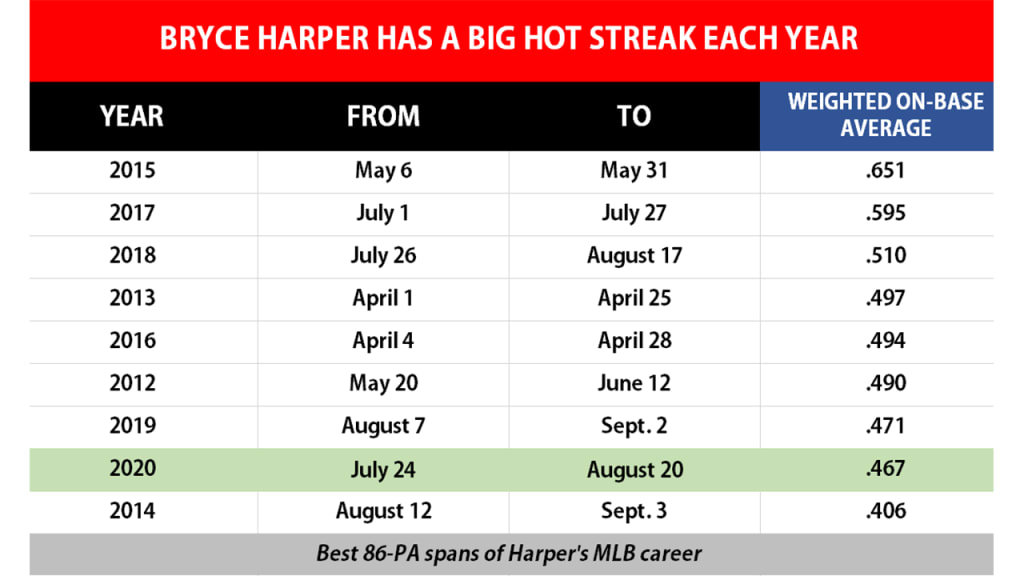

Just looking at "best months" won't do, because hot stretches can run over months, as this one has. So instead, we looked back at every 86-plate appearance stretch Harper has ever taken, eliminating overlapping ones. (We're using Weighted On-Base Average for this; think of it like a version of OBP that gives credit for extra bases. The 2020 average is .313.)

As it turns out, he has one of these stretches pretty much every year:

That monstrous stretch in 2015 isn't surprising, of course; he hit .435/.557/1.087 with 13 homers from May 6 to May 31. That 2012 run that began on May 20? It was less than a month into his Major League career. Did you realize how good he was last summer? (Hopefully! We wrote about it.)

OK, so this isn't unprecedented. You're just noticing it more because it's at the start of a season, rather than in the middle. It almost guarantees that his season line is going to look outstanding, because the Phillies are about 35% of the way through the season already, but that doesn't necessarily mean that this season is "better" than any other -- he's always good, and for a few weeks at a time, he can be great. This year, he just won't have as much time to do anything else.

Still, this isn't a total accident. So what is different here?

2) Mostly, nothing, except ...

Let's tick off the usual suspects, here.

? Is he hitting the ball harder? No. His hard-hit rate is actually slightly down from last year's 46% to this year's 43%.

? Is he elevating more? No. His ground-ball rate is slightly up from last year's 40% to this year's 43%.

? Is he walking more? A little. A 17% walk rate is very good, but last year's 15% was good too.

? Is he being shifted less? No. That's up, from 60% last year to 70% this year. (Nor is he really doing anything different against it, going opposite field 26% of the time with the shift on, and 22% when it is not.)

? Is just getting lucky? Not really. His BABIP is not in the top 30 of baseball, and his .338 average batting average is mirrored nicely by his .327 expected average, which looks at the usual outcomes of exit velocity and launch angle.

So these are all the things it's not. What is it?

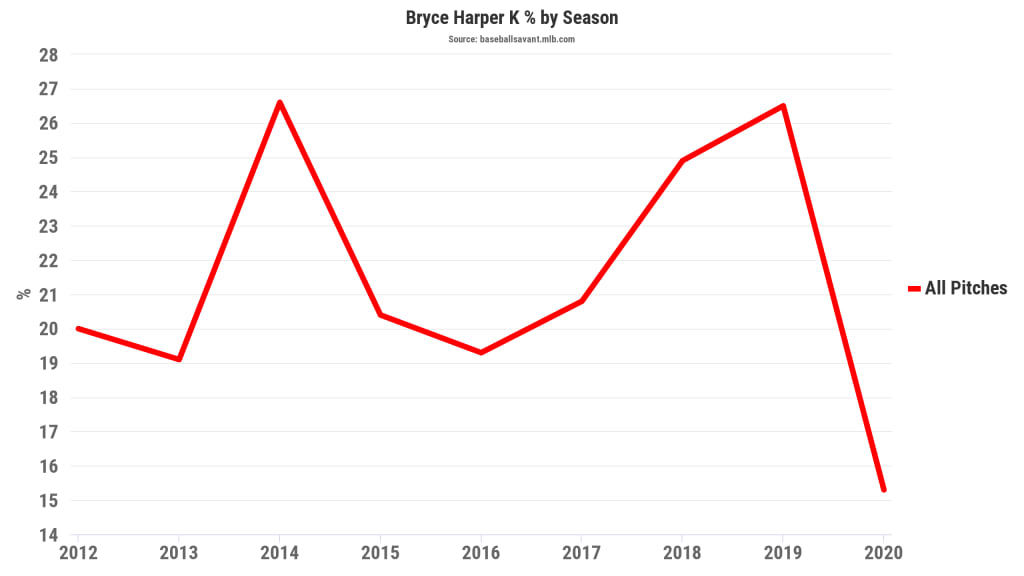

3) ... he's making more contact.

Last year, Harper struck out 26% of the time. This year, that's down to 15%. It's the third largest decline of anyone who had 400 plate appearances last year and at least 50 so far this year, behind only Rowdy Tellez and Juan Soto. That's good, right? Case closed. Look at this pretty picture. It looks like a cat. We're done.

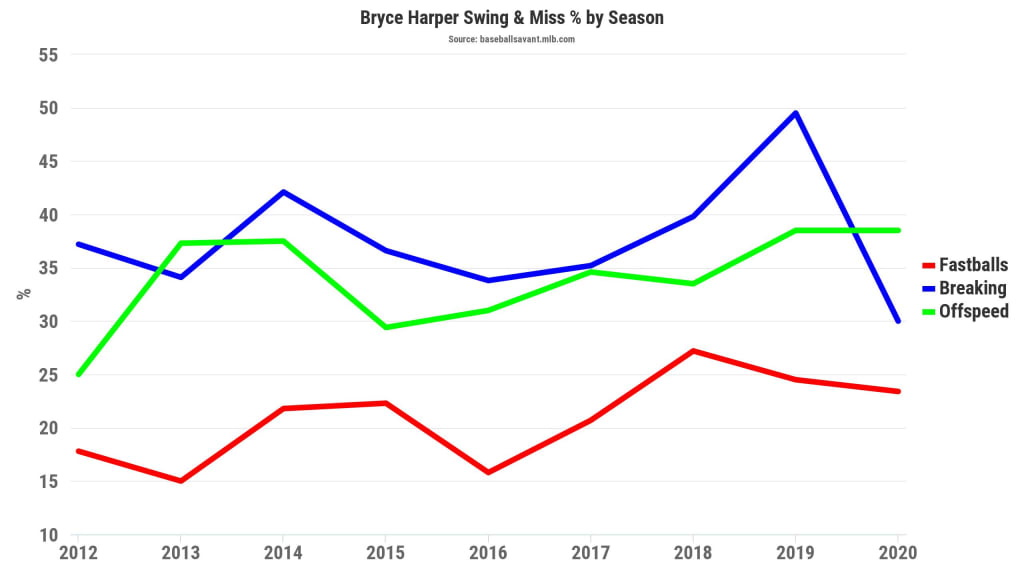

We can do better than that, of course, especially if we look at the kinds of pitching that he's swinging and missing on. Fastballs are unchanged. Offspeed pitches, like splitters and change-ups, are unchanged. But check out that blue line, the one for breaking pitches, like sliders and curveballs.

That's a drop from 50% to 30%. That's where most of the contact improvement is coming from. So what's that about?

4) He's making better swing decisions.

Let's take you all the way back to ... last June, when we wrote "how pitchers are attacking Bryce Harper." At the time, we pointed out that three things were happening:

A) He wasn't seeing first-pitch fastballs any longer.

B) He was seeing more breaking stuff before two strikes

C) On two strikes, he'd see a ton of high fastballs -- which he couldn't handle.

In 2020, most of that is still true. The difference, to some extent, is that he's getting to two strikes less than he ever has (just 24% of the time), which is partially due to him being more aggressive on the first pitch than he ever has (a 50% swing rate, which was just below 40% as recently as 2018).

But it's also about better pitch selection on those breaking pitches. It's not about fewer swings, not really; he's going after the same 49% of breaking balls he did last year. It's about better choices on which breaking balls to go after, and what happens when he does.

These numbers might jump off the page: In 2019, Harper offered at 70% of breaking balls in the zone, and 35% of them outside the zone. This year? That's 85% in the zone and just 25% of the ones outside the zone. Given that it's a lot easier to make contact on a breaking pitch in the zone than on one in the dirt, it shouldn't be surprising to see the chart we offered above -- that his swing-and-miss rate on breaking balls has fallen from 50% to 30%.

This all goes back to the "book" we just referenced -- by being more aggressive early, and making better decisions on which breakers to go after, he's helping himself avoid the situations that were most dangerous to him, which is how he's making all this extra contact.

So if we look just at breaking balls, the difference is clear.

2019: .195 BA / .414 SLG / .293 wOBA

2020: .385 BA / .462 SLG / .387 wOBA

And, it follows, that production is up on the other pitch types too, because he's not giving away at-bats on breaking pitches he can't do much with.

Let's give you a real-world example here about what that means. On Aug. 8 against the Braves, after taking a questionable first strike just off the plate, Harper watched three straight Grant Dayton curveballs go by. On the fifth pitch, he got one he could handle, and he smashed it for a double. Had he gone after any of those first three, this plate appearance maybe ends before it begins.

Pitchers will pick up on this and adjust, obviously, and even a hitter as great as Harper can't simply stop ever swinging at breaking balls outside the zone. This almost certainly goes back to "a great hitter on a red-hot streak," as these things tend to. It probably won't last, but as we said, when you're hitting this well nearly 40% of the way through the season, it barely matters. At the end of the year, his line is going to look spectacular almost no matter what happens in September.

Still, there's a reason he's been one of baseball's 10 best hitters over the last half-decade. There's a reason the Phillies gave him all that "stupid money." He's been worth that contract so far and then some. Even if the Phillies bullpen makes it difficult to appreciate, we should take the time to pay attention. When Harper is running like this, few are better.