In 2016, the year Juan Soto arrived in professional baseball, the Nationals were striking out too much. Not the big league team. The entire organization.

So Minor League hitting coordinator Troy Gingrich instituted a new rule throughout the Nats' system: Every hitter must have a two-strike approach.

A 17-year-old Soto took it to heart. And the most famed two-strike approach in Major League Baseball today was born.

"Everything started when I was in Rookie ball," Soto recalled at Citi Field this weekend. "He brought that to the whole organization. He made all the guys in the organization, they had to have a plan and a two-strike approach -- at least choke up the bat. I started choking up, getting lower in my stance and trying to just put the ball in play. Little by little, I was developing my two-strike approach. From the day I started, I felt great."

A decade later, the Mets superstar still lives by that approach. Soto's battles with the pitcher have become the stuff of legend. He can seize control of an at-bat from his opponent on the mound like no other hitter.

And Soto's batting stance is the physical foundation that lets him express his hitting genius.

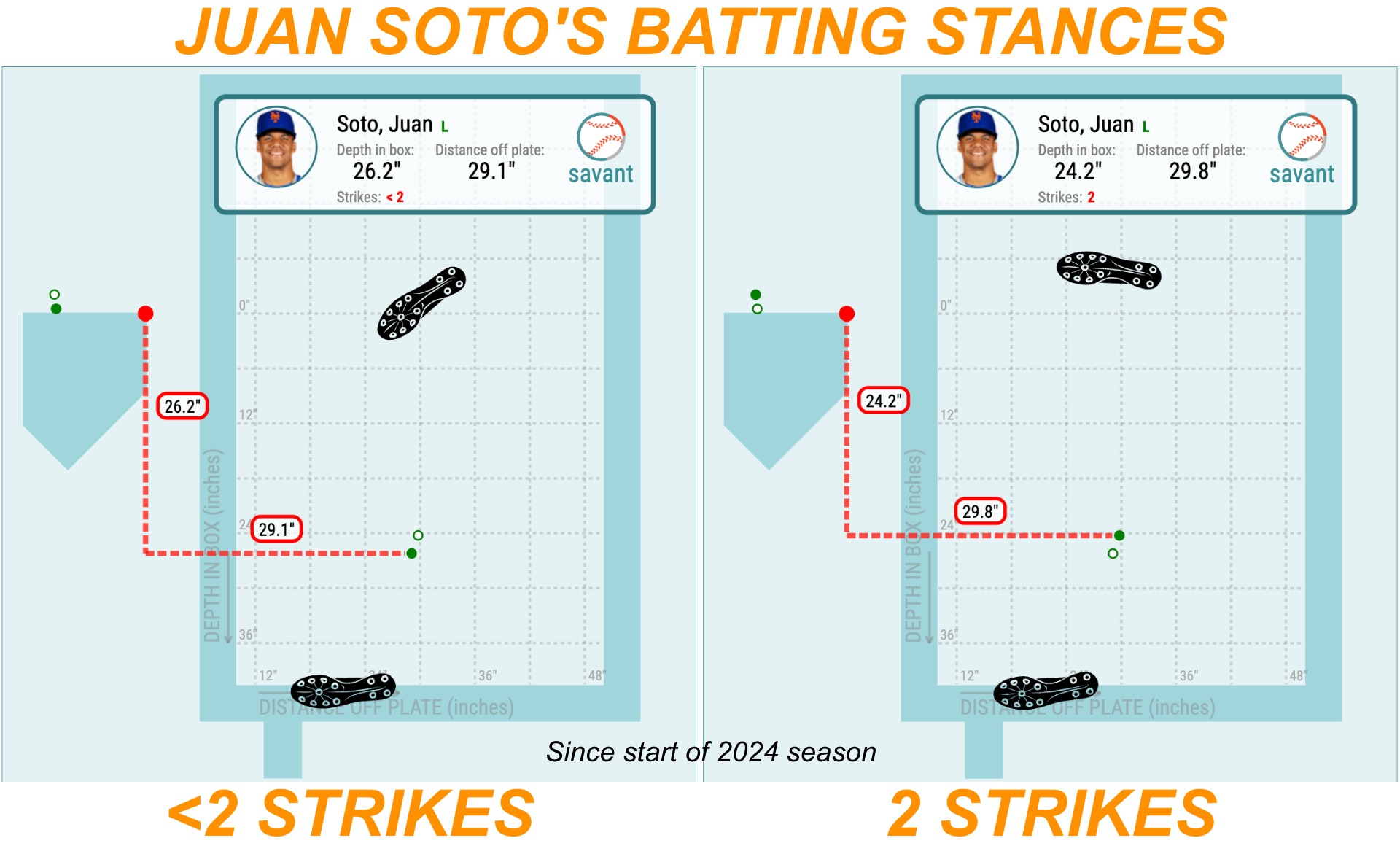

Statcast now has batting stance data available for every MLB hitter. When you look at Soto, you can see the difference between how he sets up to start every at-bat, and how he sets up once he gets to two strikes.

In his starting batting stance, Soto hooks his front foot inward, and takes a normal stride. This swing generates his incredible all-fields power -- home runs launched from foul pole to foul pole. Before Gingrich and his two-strike-approach mandate, it was the only swing Soto knew.

"That was all the time -- two strikes, no strikes," Soto said. "That's how I used to be."

But now he has the two-strike batting stance to complement it. Soto digs in, his feet square to the pitcher and flat on the ground. He widens his base, lowers his foundation and takes a much more abbreviated step. These are his cues to ensure he keeps his swing compact as he enters his showdowns with opposing pitchers, prepared to fight off their best stuff until he can make square contact.

"When I go down like that, it's more about choking up, less movement and try to be shorter to the ball," Soto said. "That's the mindset when I get to two strikes. With the foot turned, I can be a little higher, leg kick and everything. But whenever I put my foot flat, the leg kick is almost like you're not even coming off of the ground. I do that to just keep it simple."

Every piece of the stance has a purpose. Soto is extremely intentional in the batter's box. It helps make him great.

His trademark inwardly angled front foot, for example -- a setup only a few other hitters, like Corey Seager, use. That goes back far longer than Soto's two-strike approach, to when Soto was 14 or 15 years old and still a fledgling hitter in the Dominican Republic. But even the origin of that batting stance idiosyncrasy came with a specific hitting goal in mind.

"I started that way before I signed as a professional baseball player," Soto said. "It was one of those weeks and months that I felt like I was pulling everything and coming off everything. So I was trying to figure out how to keep my hip tight and square to the pitcher. I was coming [around] too quick. One day, I came up with: Start turning my feet so I can keep my hip in line to the pitcher. It worked, and I just kept doing it all the way."

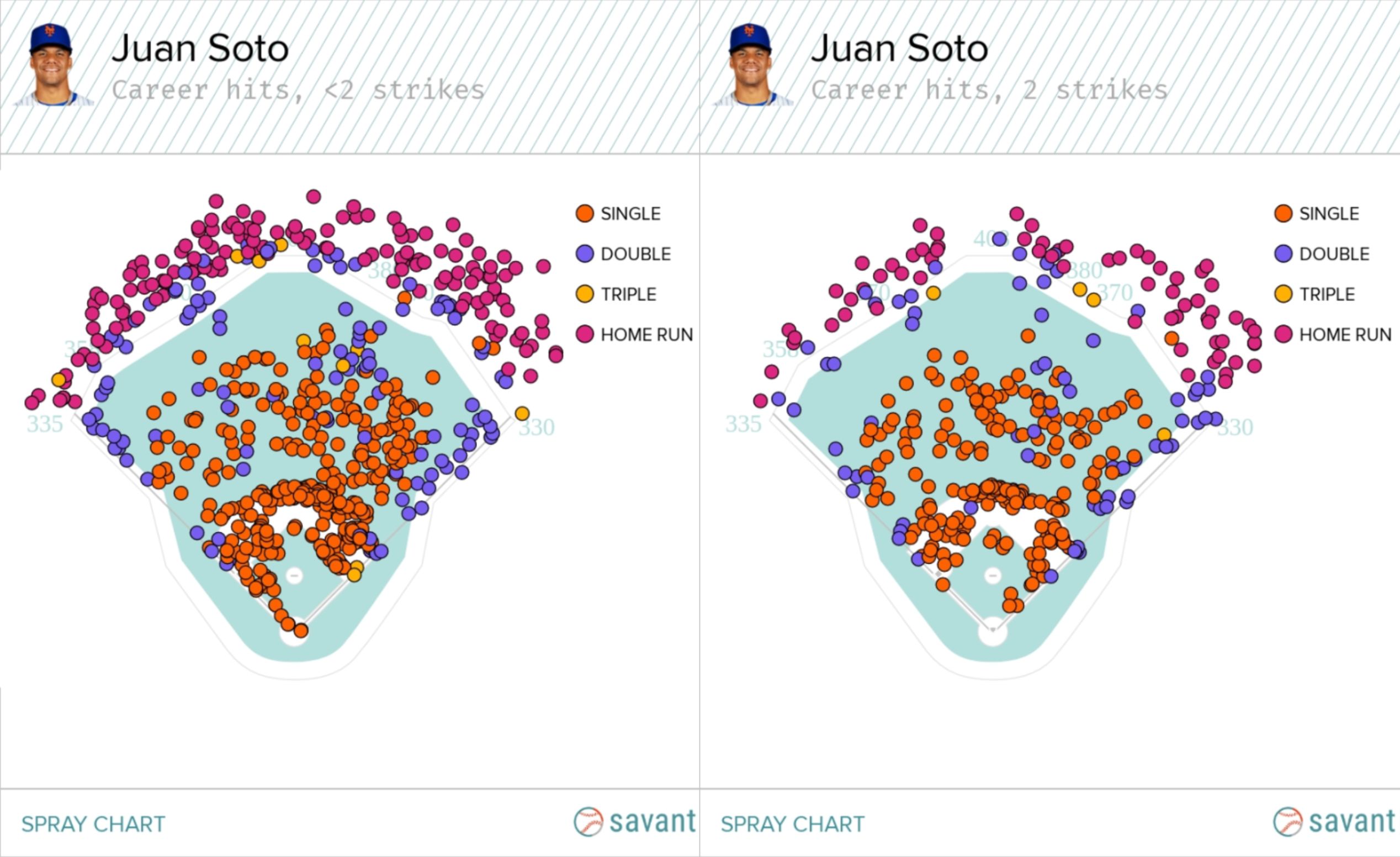

Now Soto is renowned for being able to stay in against any pitch and drive the ball in any direction. The spray chart of his base hits covers the entire field, whether he is hitting with two strikes or less than two strikes.

Across eight big league seasons and four different teams, Soto has never wavered from this approach, the one he learned in Rookie ball. He has used, fundamentally, the same dual stances for his entire Major League career.

Watch an at-bat by a 19-year-old Soto in his debut season with the Nationals in 2018, or from their World Series run in '19. His setup will look more or less the same as Soto in 2024 with the Yankees or 2025 with the Mets.

There has been some gradual evolution over the years, as Soto has tweaked his stance to match the changes in the game, especially the rise of flamethrowers. Major League pitchers in 2025 are not the same as pitchers were in 2018. Soto knows he would be foolish not to adapt.

"There are more 100 [mph] throwers than when I came up to the league," Soto said, laughing at the recollection of what the game used to be like. "When I came up to the league, I remember, it was probably one per team. You'd probably see 100 mph once a month. Nowadays, there are so many guys throwing 100 mph, and little by little, you've got to change the way you try to catch up to those pitches."

So Soto has adjusted his hand position, bringing his hands lower and closer to his back shoulder to get into his swing quicker -- something other sluggers have done, too, with Soto citing Vladimir Guerrero Jr. and Rafael Devers as examples.

"You see Vladdy, he changed his hands from up to down, because everybody's throwing so hard. Devers, same thing. His hands -- up, down," Soto said. "Before, everybody could have their hands up high and try to launch from there."

He's also a little less hunched over in his two-strike stance, but sinks down more with his legs, which helps him get off his shorter two-strike swing in time to catch up even to extreme velocity.

But the principles powering his iconic swing have stayed the same.

Switching between two unique stances, one for two strikes and one for not, has become something of a lost art in Major League Baseball today. It is increasingly common for hitters to try to deploy the same "A swing" no matter the situation.

But Soto believes that all great hitters have a two-strike approach. His is just more visible. And he's so good that it's not an "A" swing vs. "B" swing, it's just two different A swings -- one for power, one for contact.

"If you ask every good hitter, there are a lot of them out there who don't change their stance, but they change their mentality," Soto said. "That's probably why you don't see that many [using two stances], but definitely I feel like most of the good hitters, they have a two-strike approach. For me, I definitely have to change my stance and try to be shorter, because that's how I learned it, to go about the two-strike approach. They learned it a different way, they do it a different way."

For Soto, the mental approach is manifested physically in his batting stance. He has one of the biggest differences between two strikes and less than two strikes of any hitter today.

Soto's batting stance is 40 inches wide with less than two strikes -- that's the distance between his feet. He widens that to 45 inches once he gets to two strikes.

Biggest change in stance width, 2 strikes vs. <2 strikes

Since start of 2024 season

- Lawrence Butler: 11 inches wider

- Alec Burleson: 10 inches wider

- Nolan Schanuel: 7 inches wider

- Ryan Jeffers: 5 inches wider

- Juan Soto: 5 inches wider

The spread stems from how Soto orients his feet in the batter's box. When he points his toe inward and raises his heel off the ground to start an at-bat, that narrows his stance and lets him take the stride for his "power" A swing. When he rotates his foot back to even and keeps it flat on the dirt with two strikes, that widens his base and sets up his "contact" A swing.

"I feel like I have the same power with two strikes or before two strikes," Soto said. "I just feel like I'll be able to drive the ball a little bit more to the opposite-field side [before two strikes]. I definitely can hit it with power [with two strikes], but I feel like I can drive it a little more and probably control it a little bit more before two strikes. And then when I get to two strikes, I just try to slap it that way. I've hit homers before, like that, but I just try to put the ball in play."

The change in his setup also brings Soto slightly more in line with the pitcher. His batting stance angle is 15 degrees "open" with less than two strikes. (That is, his front foot is closer to the outside edge of the batter's box than his back foot.) His two-strike stance cuts that angle down to 9 degrees open. It's a subtle shift, especially to the naked eye, but it gears Soto toward the philosophy he takes with two strikes: protect the plate, fight off pitches, hit a line drive up the middle or to the opposite field, or work a walk.

"I keep being aggressive," Soto said. "But even with my strike zone, I try to make it a little wider and try to protect more, instead of trying to drive the ball more. For me, that's the mindset."

Let's go back to that first year in the Minors in 2016, when Gingrich decided the Nationals' young hitters needed to stop striking out so much.

In Soto's first professional season, when he was still developing his two-strike approach, he finished with 17 walks and 29 strikeouts (he also hit .368). But by the start of his second year, he had grown comfortable with it. He started walking more than he struck out -- Soto had 12 walks to only nine K's in 32 Minor League games in 2017, and 29 walks to 28 K's in 39 games in 2018.

Then he was in the Majors. And after he learned the Major League game as a teenager, he only got better. Soto's plate discipline is all-world. He's had more walks than strikeouts in each of the last five seasons, and he does again so far in 2025. In his career, even after reaching two strikes, Soto still gets on base in a third of his plate appearances, the best of any hitter since 2018. The average Major League hitter does so in less than a quarter of theirs.

"As I was working to try to take more walks, [the two-strike stance] helped me," Soto said. "Because when I got to two strikes, I wasn't just swinging and trying to drive the ball to the outfield. I was just trying to put the ball in play. It helped me to develop the strike zone that I have right now."

What you see now is the modern-day reincarnation of Ted Williams, a once-in-a-generation hitter whose yin-and-yang batting stances are what everything flows from.

"I'm at a point right now with my body where, when I get to two strikes, it's just automatic," Soto said. "You just go do two-strike-approach things."