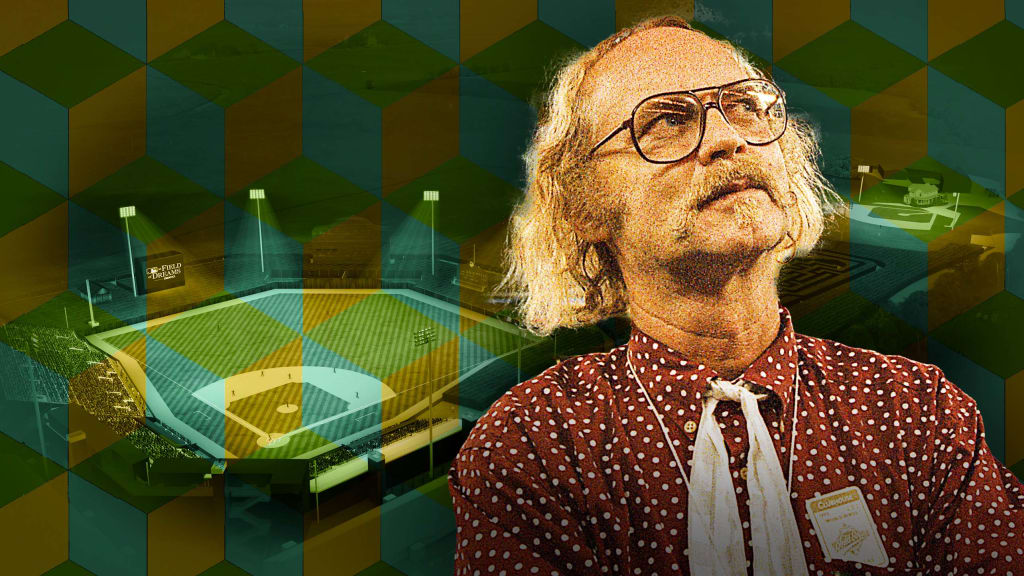

Forget "If you build it, he will come" -- the most famous line from "Field of Dreams" -- because if author W.P. Kinsella had listened to his guidance counselor, Mr. McCoy, there never would have been the book, "Shoeless Joe," to adapt in the first place.

While in high school, Kinsella was ushered to the guidance counselor's office to discuss his plans for the future. Kinsella said that he dreamed of being a writer. But, rather than offering encouragement or suggestions on how to pursue that path, McCoy gave a ten-minute lecture on just what a bad idea that would be, instead pressuring the young dreamer to enter a more traditional career. He should choose engineering, accounting or law, McCoy argued, while writing as a hobby on the side.

Suffice to say, Kinsella did not appreciate that feedback.

"I think there is a special place in hell for [McCoy]," Kinsella, who passed away in 2016, told his biographer, Willie Steele, in the book "Going the Distance."

Then again, considering that "Shoeless Joe," is about a man trusting a voice in a cornfield rather than listening to reason, perhaps it's only fitting that it mirrors Kinsella's life, too.

For a man who is best known in the United States for his baseball fiction, naturally, Kinsella's first-ever piece was about baseball, too. He was 14 when he wrote "Diamond Doom," a short story about a murder at a ballpark during a local YMCA competition. Though that story is long gone, misplaced during one move or another in Kinsella's life, it was the first of what would one day become eleven novels and short story collections about baseball.

So, it's somewhat shocking that Kinsella wasn't raised knowing how to play the game. Though his father played third base for commercial teams in his youth, Kinsella didn't get to play baseball or see a game until he was ten years old. Born on May 25, 1935, in a small town near Edmonton, Alberta, Kinsella was homeschooled until the fifth grade. Only when the family moved and Kinsella started attending school with other children did he get his first taste. Called up to bat on a whim one day, he made contact, lining the ball into the outfield. Unfortunately, he didn't know to run to first base, and the embarrassment he suffered as his peers made fun of him lived with him the rest of his life.

"Children are especially cruel to anyone who is different," Kinsella said, "and I had all my weaknesses pointed out in no uncertain terms."

He saw his first live action that year, taking in a semi-professional contest at nearby Renfrew Park, home to teams like the Edmonton Trappers. Soon, he fell head over heels for the sport while listening to the 1946 World Series champion Cardinals on the radio, becoming "enthralled with names like Harry 'The Cat' Breechen, Howie Pollet, Red Schoendiest, Terry Moore and Joe Garagiola," Steele wrote. Still, it would take until his collection, "Shoeless Joe Jackson Comes to Iowa," was released for Kinsella to begin writing more baseball fiction. Once he did, he never stopped.

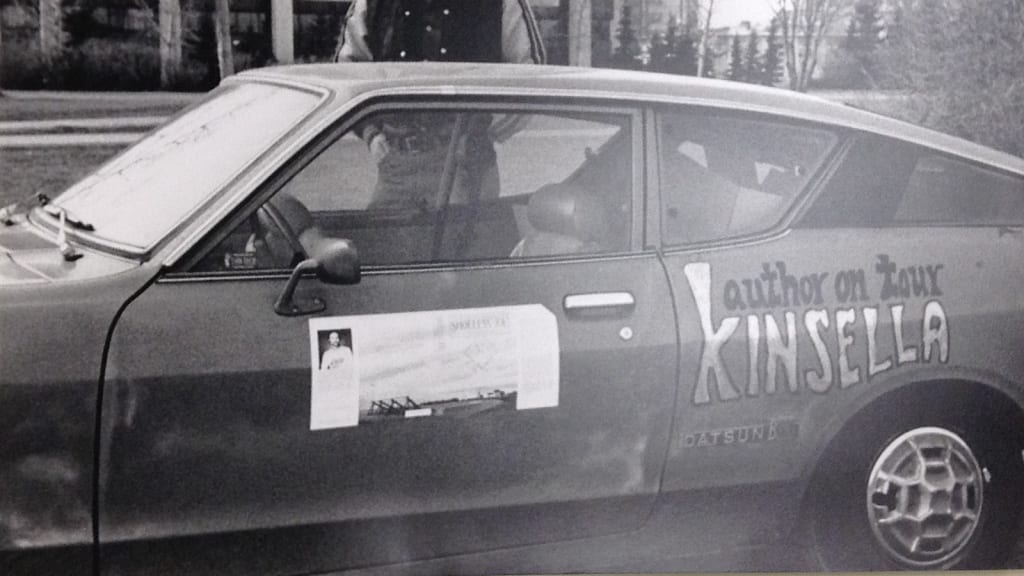

"It was only after [its release] in 1979 that it exploded," Steele said in a recent phone call. "It really was just this wave of baseball literature for the rest of his career. His thought was, 'If that's what they want, I'm gonna keep writing it until they don't want it anymore.'"

While part of that decision may have been commercially-minded, Kinsella was a baseball fanatic. He and his third wife Ann Knight were season ticket holders for the Mariners and he had an almost "religious commitment level to rotisserie baseball," Steele said. "They would do drafts and he was hyper-competitive, crazy competitive. So, he was always checking the box scores."

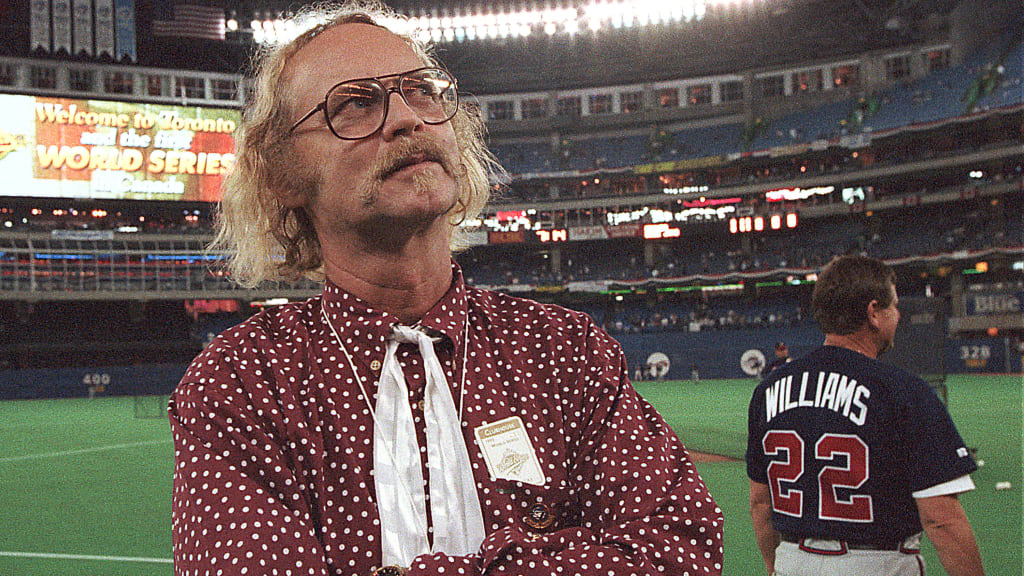

When he was on book tours, he would catch games at the local Minor League parks or he'd head to a nearby Major League game. He was even a "card-carrying scout for the Atlanta Braves," Steele noted. Though it was meant to be largely honorary and he never found anybody that Atlanta ended up acquiring, "Kinsella claimed that he was always on the lookout for good ballplayers."

Baseball not only allowed Kinsella to be successful enough to leave his other jobs, but it also enabled him to tell the stories he wanted to share.

"There¡¯s theoretically no time -- you know, baseball can go on forever," Steele said. "The other thing is, there's no limit to how far somebody can can hit a ball, how far somebody can run to catch a ball. And so he incorporates those types of things. And he says, it's a lot like our day-to-day lives. There's a lot of mundane, really, quite frankly, boring things. And then there are these moments -- you know, [Bill] Mazeroski in the bottom of the ninth in 1960, or Joe Carter in '93, and stuff like that."

Baseball resonated with his readers in a way other sports can't. "None of us can envision what it's like to be a seven-foot-tall NBA player, but how many of us have watched baseball and thought, 'I can do that?' I mean, Greg Maddux looked like somebody's tax guy," Steele joked.

Though Kinsella may have loved the game and the magic it provided, he had no interest in pursuing it as a beat writer or filing essays for newspapers or magazines.

Adding the foreword to Scott Morrison's book, "Back 2 Back" about the 1992-93 World Series champion Blue Jays, Kinsella didn't mince words or hand out compliments just because it was expected. ¡°Was it a great World Series for Toronto? You better believe it," Kinsella wrote. "Was it a great World Series? No.¡±

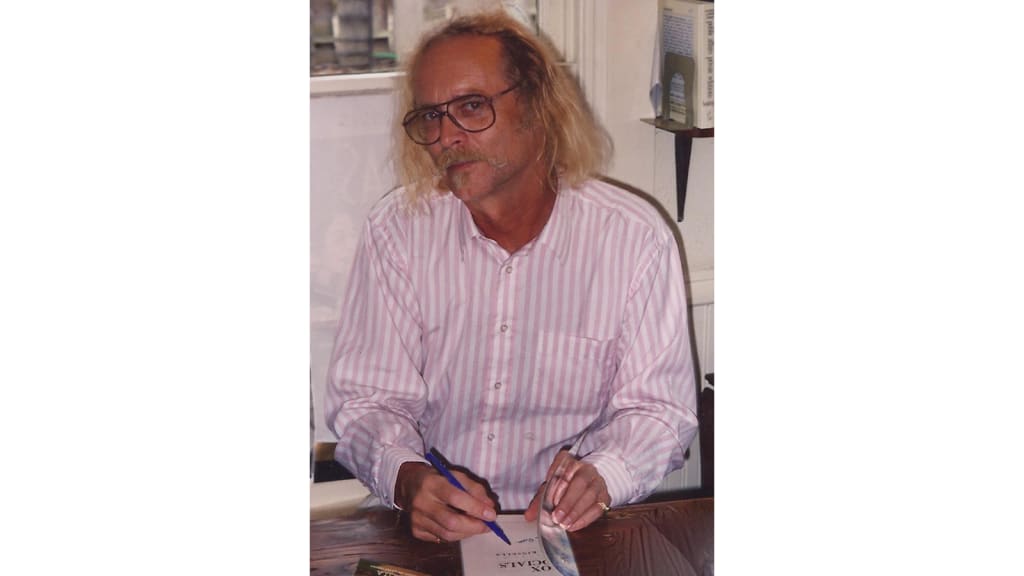

"His strength was certainly the fiction writing," Steele said, "because in his mind, he said, 'I don't have to stick with facts, if I need a fact I can make it up.'¡±

But just as it may have seemed odd to editors who wanted Kinsella to use his unique viewpoint on the game out on the field, Kinsella himself is a study in contradictions.

His stories are filled with magic, whimsy and ghosts from the past coming back, like in "Searching for January," about a man running into Roberto Clemente on a beach in 1987, years after the accident that took his life. Then there's "The Fadeaway," where a relief pitcher gets tips from Christy Mathewson on how to throw the fabled pitch on the bullpen phone.

But Kinsella despised the supernatural and had no time for it or the people who did believe.

He filled his tales with biblical allusions. Ray Kinsella hearing voices telling him to build a field is "like Abraham, Moses or Noah," Steele points out, and the "The Iowa Baseball Confederacy" features a 2,000-inning game that goes for 40 days and 40 nights.

"Look, I think the Bible is a great story," Kinsella told Steele. "It's not true, but that doesn't mean it can't have really good stories."

His tales are filled with quirky, relatable characters and love that stretches through time. But Kinsella was a curmudgeon, his life motto summed up by his go-to phrase: "I don't suffer fools gladly."

His first published stories -- the ones best known in Canada and which he would return to throughout his career -- are told from the perspective of Silas Ermineskin, a member of the Cree tribe. While many of the stories are humorous, many critics claimed the tales were cultural appropriation at best, often falling on ¡°easy and lazy¡± racist stereotypes.

And then, there are the bonds between fathers and sons, like the one at the center of "Shoeless Joe." Kinsella had a poor relationship with his father, struggling to connect with him when he was young and calling him a coward for going back to the church when he was ill with stomach cancer.

Perhaps that's what Kinsella was doing when he sat down at his desk; he was working through the issues he couldn't deal with himself.

"He would have told you that it's only fiction," Steele said.

"The great thing I think about the novel and the film, is, if you've got a really terrible relationship with people, it's that sense of wanting to do it better," Steele added. "And if you've got a great relationship, it's that you always want one day more. If you lose a parent, if you had the opportunity to have one day more, at the end of that day, you would want one day more, and I think Kinsella really knew that."

But maybe there was a little magic in Kinsella's life -- even if he didn't believe it. How else can you explain the little movie about a supernatural cornfield becoming the beloved classic it is today, one inspiring the Yankees and White Sox to play in Iowa on Thursday night?

The only reason Kinsella ever considered expanding his short story into a novel was at the behest of editor Larry Kessenich, who reached out to Kinsella and urged him to do it. At the time, Kessenich was only an editor's assistant and had never edited a novel.

After the film rights had been sold, they passed from movie studio to movie studio -- usually a sure sign that a project is doomed long before it ever gets in front of a camera.

The film's director, Phil Alden Robinson, didn't seem like a good match for the project, either. "Phil wasn't into farming. He's not a spiritual person, not into the mysticism of ghosts and hearing voices," Steele said. "This movie should never have been made."

Even Steele, who wrote a literary analysis of Kinsella's work and before being brought on to write his biography, saw the film through sheer chance. He was supposed to see "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade" with his brother and friends, but on an impulse opted to watch "Field of Dreams" on his own.

"I mean, this changed [my life], it mapped out the trajectory of my professional life," Steele said. "I didn't know it. My favorite line in the novel is when Moonlight Graham says, 'Hardly anybody recognizes the most significant moments of their life at the time they happen.' And I think that's true for all of us."