A version of this story originally appeared on MiLB.com in 2006. We present it here once more as Minor League Baseball celebrates Black History Month with stories of Black baseball pioneers.

Every baseball player dreams of playing in the World Series. For decades, prospects had the chance to experience a tiny sample of that glory before they even reached the Majors.

Between 1931 and 1975, a "Junior" or "Little World Series" often took place between the best upper-level teams in Minor League Baseball. Perhaps the most notable such series took place in 1946, when Jackie Robinson's International League champion Montreal Royals defeated the American Association's Louisville Colonels, four games to two.

"The Little World Series was special in that day," Louisville infielder Al Brancato told MiLB.com in 2006. "There were a lot of big league players in Triple-A, a lot of guys just out of the service."

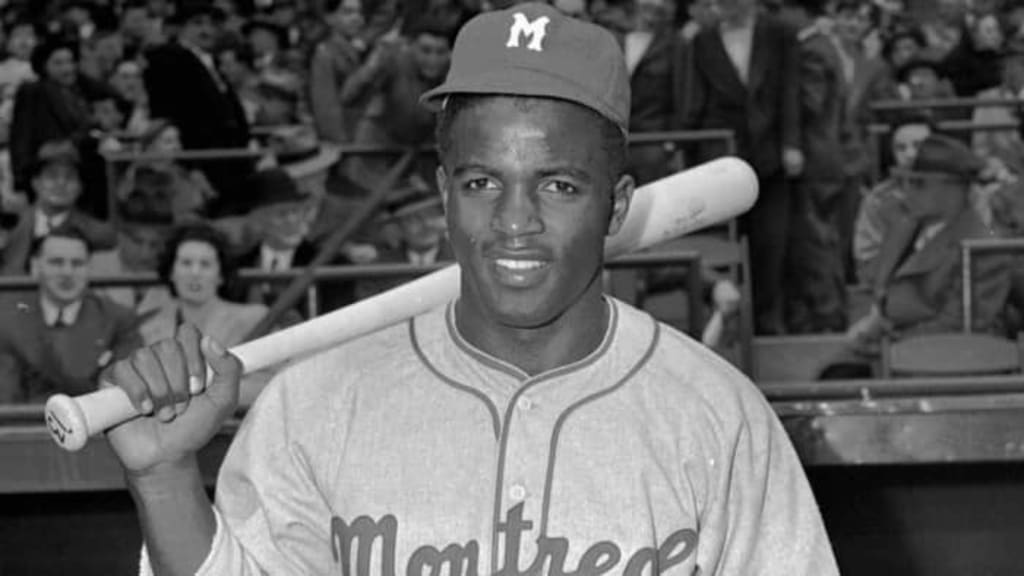

Jackie Robinson's first year integrating baseball was 1946, and his spectacular season with the Royals served as a precursor to the success he would achieve at the Major League level. While carrying the weight of enormous social ramifications, the 27-year-old led the league in average (.349) and runs scored (113), while stealing 40 bases and driving in 66 runs. Almost as impressively, he drew 92 walks against just 27 strikeouts. Robinson's performance sparked the Royals to a 100-54 record.

"We were a real well-rounded team," recalled catcher Herman Franks. Franks, who played six Major League seasons before going on to a seven-year managerial career with the San Francisco Giants and Chicago Cubs, spoke to MiLB.com three years before his death, at age 95, in 2009.

"We didn't have a 20-game winner, but we had a lot of good hitters, played good defense and had plenty of speed. It was Jackie's first year in [affiliated] baseball. He was a great teammate, but really had a tough time breaking in. Back then, Baltimore was still considered part of the South. We played there in the beginning of the season, and they wanted to know if we were really going to come out on the field with a Black player. They didn't want to play the game. We said, 'Well, you don't have to play, but we're still going out there.'"

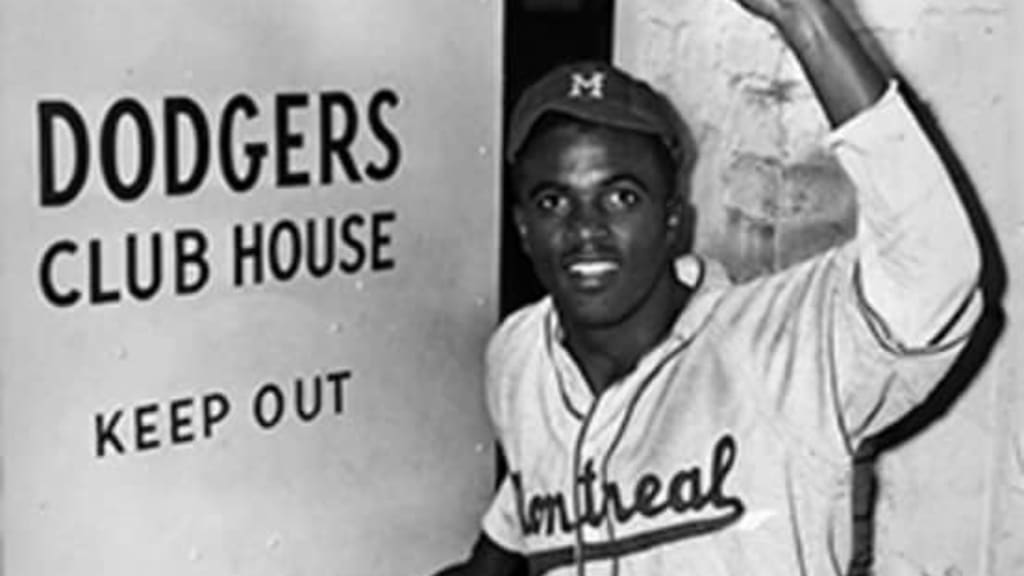

Montreal was a different story. The city's French-Canadian fan base embraced Robinson from the start of the season, and by the time the Junior World Series rolled around, he had become a bona fide hero. However, the first three games of the series were scheduled to be played in Louisville, a considerably more hostile area.

"It was a very exciting time, because of all the controversy surrounding Jackie being the first Black player," said Brancato, who died at the age of 93 in 2012. "Jackie didn't even have a place to stay. There were no hotels that would take him, so they didn't even know whether or not they were even going to play."

Louisville's fans brought this unwelcoming attitude to the stadium too.

"Everything he did, they booed him," Colonels pitcher Otey Clark said in 2006. "I remember our pitcher, Jim Wilson, knocked him down and the fans cheered. Robinson didn't seem to pay any attention to any of it."

The fans, nonetheless, may have had an effect on Robinson, as he went 1-for-10 over the three games in Louisville. The series then moved to Montreal with the Colonels holding a 2-1 lead. There, Robinson found the Royals' fans were livid over the rude welcome he had received in Louisville.

"We discovered that the Canadians were up in arms over the way I had been treated," said Robinson in My Own Story, his 1972 autobiography. "Greeting us warmly, they let us know how they felt. ... All through that first game [at home] they booed every time a Louisville player came out of the dugout. I didn't approve of this kind of retaliation, but I felt a jubilant sense of gratitude for the way Canadians expressed their feelings."

During that first game in Montreal, the series' momentum swung decisively in the Royals' favor. Clark took a two-run lead into the bottom of the ninth inning, but walked the bases loaded and allowed Montreal to tie the game.

"It was my most embarrassing moment in baseball," said Clark, who died in 2010. "I hadn't needed anyone to relieve me all season, but they tied it up and beat us in extra innings."

In fact, it was Robinson himself who drove in the winning run in the 10th. In Game 5, he went 3-for-5 with a triple, a double, two runs scored and an RBI in the Royals' 5-3 victory. One day later, he collected two hits in the Royals' 2-0 series-clinching win.

Montreal's triumph sent the city's fans into a joyous delirium. Knowing Robinson was headed for the Major Leagues in 1947, they demanded he come back onto the field for a final curtain call. As soon as he emerged, the crowd went wild. Robinson's friend, Sam Maltin, described the scene in the Pittsburgh Courier:

"Jackie came out and the crowd surged on him. Men and women of all ages threw their arms around him, kissed him and pulled and tore at his clothes, and then carried him around the infield on their shoulders, shouting themselves hoarse. Jackie, tears streaming down his face, tried to beg off further honors."

The pandemonium continued outside of the stadium. Hundreds of fans chased Robinson through the streets as he attempted to make it back to the team hotel.

"It was probably the only day in history that a Black man ran from a white mob with love instead of lynching on its mind," wrote Maltin.

Decades later, the improbable ending to an improbable season remained fresh in the minds of those who witnessed it. Robinson played the game under exceedingly adverse circumstances, but still managed to prevail.

"I know he was a heck of a ballplayer," said Brancato. "There was nothing delicate about him. He did everything rough and tumble -- there was always dust. But he was very quiet, even with all the commotion around him."