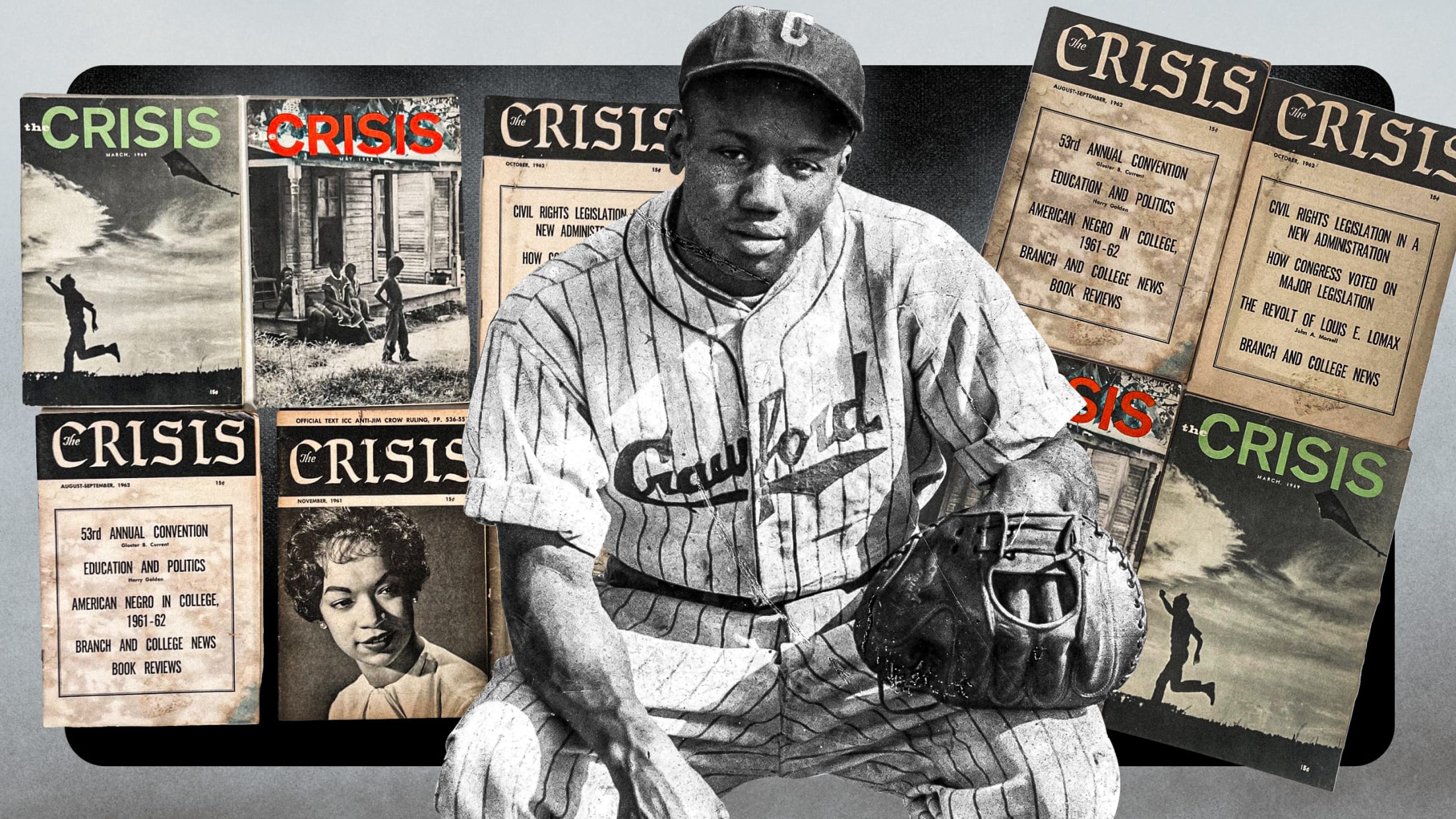

The only time Negro Leagues legend Josh Gibson graced a magazine cover

My friend Dr. Steven Lomazow has an unparalleled collection of American periodicals in all genres. That collection was the basis of a 2021 exhibition at the Grolier Club, ¡°Magazines and the American Experience: Highlights from the Collection of Steven Lomazow, M.D.¡± It was accompanied by a catalogue to which I contributed (still available from The University of Chicago Press).

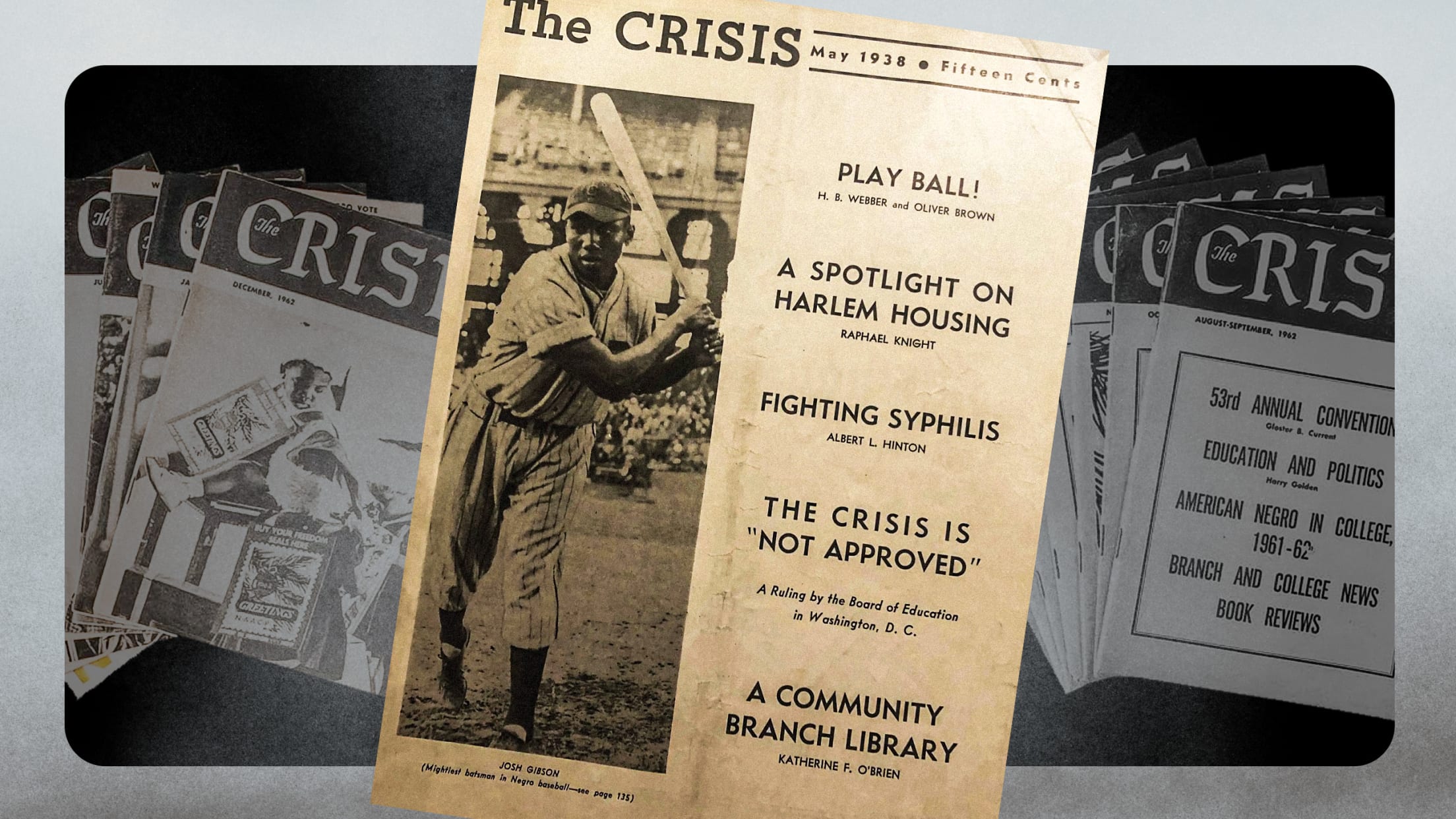

In an email after the exhibit, Steve shared an exciting new acquisition: the May 1938 issue of The Crisis, founded by W.E.B. Du Bois in 1910. In the November 1910 premier issue of The Crisis, Du Bois noted that The Crisis would be a "a record of the darker races."

The Crisis was subsequently edited by Roy Wilkins and, to this day, is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Missing from the publication¡¯s own archives, this issue of the monthly might have been presumed lost.

What prompted Steve to share it with me was its cover, the only periodical known to have featured Josh Gibson, the premier slugger of the Negro Leagues. The featured article is presented below; of particular interest to readers today may be the section on possible racial integration.

***

Play Ball!

By H.B. Webber and Oliver Brown

May 14 will see the opening of the organized Negro baseball season. Here is a bit of history and a few comments on the national game.

One million baseball fans in eastern and western cities watch 15 teams in the two major Negro leagues play organized baseball each year from May 15 until September 15 and in these months they see batters as great as Babe Ruth and pitchers more colorful, and skillful as Dizzy Dean or Lefty Gomez.

These 15 teams spend on an average of over half a million dollars a season in overhead, salaries, publicity, the finest of uniforms, and transportation. Each maintains spring training camps in the South just as the major leagues do. The two leagues meet regularly, trade players, make outright purchases of players, decide on regulation balls to use, experience ¡°hold-outs¡± and duplicate the activity of the majors in practically every detail ¡ª to such an extent that both weekly and daily newspapers throughout the country have insisted that top-notchers in the colored leagues be taken into the big leagues.

And such names as Leon Day, Satchell Paige, Cool Papa Bell, Willie Wells, Johnny Taylor, Newt Allen, Chet Brewer, Sammy Bankhead, Josh Gibson, Ted Strong, Turkey Stearnes, Andy Cooper, Mule Suttles, Streak Milton, Floyd Kranson, Alex Radcliffe, Ray Perkins, Biz Mackey, Slim Jones, Jud Harris, Red Redus, and Terris McDuffie may be one day as familiar to the white baseball fans of the nation as they are to the million colored fans today.

Three years ago a number of men with money turned their attention to Negro baseball. Among these were Gus Greenlee of Pittsburgh who was destined to exert a tremendous influence over baseball in the years to follow. In 1934 Greenlee headed the move to organize the Negro National League. This league was composed of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, Homestead Grays, Newark Dodgers, Nashville Elite Giants, Philadelphia Stars, Cleveland Red Sox, Chicago American Giants, Bacharach Giants, and the Baltimore Black Sox.

Despite many handicaps and reverses, the league was able to complete the first years successfully. In 1935 the Brooklyn Eagles and the New York Cubans became members while the Cleveland Red Sox, Baltimore Black Sox, and the Bacharach Giants dropped out. Only a few changes have taken place in the league since the first year with the exception of the granting and transferring of franchises. In 1936 the Brooklyn Eagle took over the Newark Franchise and became the Newark Eagles; Nashville Elite Giants moved into Washington; the Black Yankees became a member and the Chicago American Giants disbanded.

Despite hundreds of doubting Thomases, it is safe to predict that organized Negro baseball is here to stay. The owners of these clubs are sincere and have invested thousands of dollars in fine buses, parks, and players, and sundries to give to their followers the best in league baseball.

H.B. Webber and Oliver Brown

Season Opens May 14

Last year the league operated with six teams and this season, which opens May 14, will see eight teams representing Washington, Baltimore, New York, Newark, Pittsburgh, Homestead, Pa., Buffalo and Philadelphia competing.

Last season a group of baseball men in the West organized the American Negro Baseball League and completed a most successful and encouraging season. Baseball interest, which had been on the wane for several years, was revived and the league looks forward to making money in the second year of operation. Both leagues have a working agreement on players and will also be under the jurisdiction of one commissioner. At the conclusion of this season¡¯s league schedule, a World Series will be staged between the winning teams of the respective leagues.

In the American League are H.G. Hall¡¯s Chicago American Giants, J.L. Wilkinson¡¯s Kansas City Monarchs, T.R. Strong¡¯s Indianapolis A.B.C.¡¯s; H.L. Moore¡¯s Birminghams; and teams in Atlanta, Mounds, Ill., and the Jacksonville Red Caps.

The National League is run by a board of three men ¡ª Abe Manley of the Eagles, Gus Greenlee of the Crawfords and Tom Wilson of the Elite Giants. The American League is bossed by Major R.R. Jackson, chairman.

In the past Ferdinand Q. Morton of New York, Rollo Wilson of Philadelphia, and Judge W.C. Hueston of Washington have held the post of baseball commissioner, arbiting between the two leagues. At the moment this post is vacant. At the June meetings of the leagues in Pittsburgh a new commissioner is expected to be selected. One name mentioned most prominently is that of Magistrate Joseph Rainey of Philadelphia.

League meetings in east or west are as lively and draw as much interest among baseball enthusiasts, sportswriters, and other folk as any meeting of the big leagues.

Release at these meetings of the seasonal schedule is but one big job completed. These schedules affect many lives, not only of the players, but of the thousands of fans. A second big task is the effecting of player trades and releases. Not publicized so much are the prices and wages of the players, but trades call for shrewd bargaining of the cash value of big player names.

Despite hundreds of doubting Thomases, it is safe to predict that organized Negro baseball is here to stay. The owners of these clubs are sincere and have invested thousands of dollars in fine buses, parks, and players, and sundries to give to their followers the best in league baseball. Men like Gus Greenlee, Abraham Manley, Tom Wilson, Cum Posey, Edward Gottlieb, Edward Bolden, and ¡°Sonnyman¡± Jackson are due real credit for their sacrifices in maintaining organized Negro baseball.

There are few improvements in the operation of the league which should be made as soon as possible. Among these are:

1. A league statistician should be employed to compile individual and team averages and standings.

2. A central booking agency should be maintained by the league to draw up the schedule and book exhibition games. This would mean a saving to the clubs in fees and would also take them from under the domination and mercy of white booking agencies.

3. The establishment of a publicity bureau to sell league baseball to the public.

4. A league commissioner with the powers of Judge Landis.

Fascinating History

Negro baseball is not a new development. It has a long and fascinating history. To the immortal Rube Foster goes the credit for being the person to pioneer in giving our race organized baseball. Previous to this, Negro baseball was of an independent, gaudy type, resembling and retaining most of the objectionable features of the traveling carnival. Owners reaped a rich harvest in playing independent white ball clubs. For this Negro baseball suffered.

White fans, who attended and supported the major leagues, looked upon these contests as mere novelty and usually judged the caliber of Negro players by their success against third-rate independent white clubs.

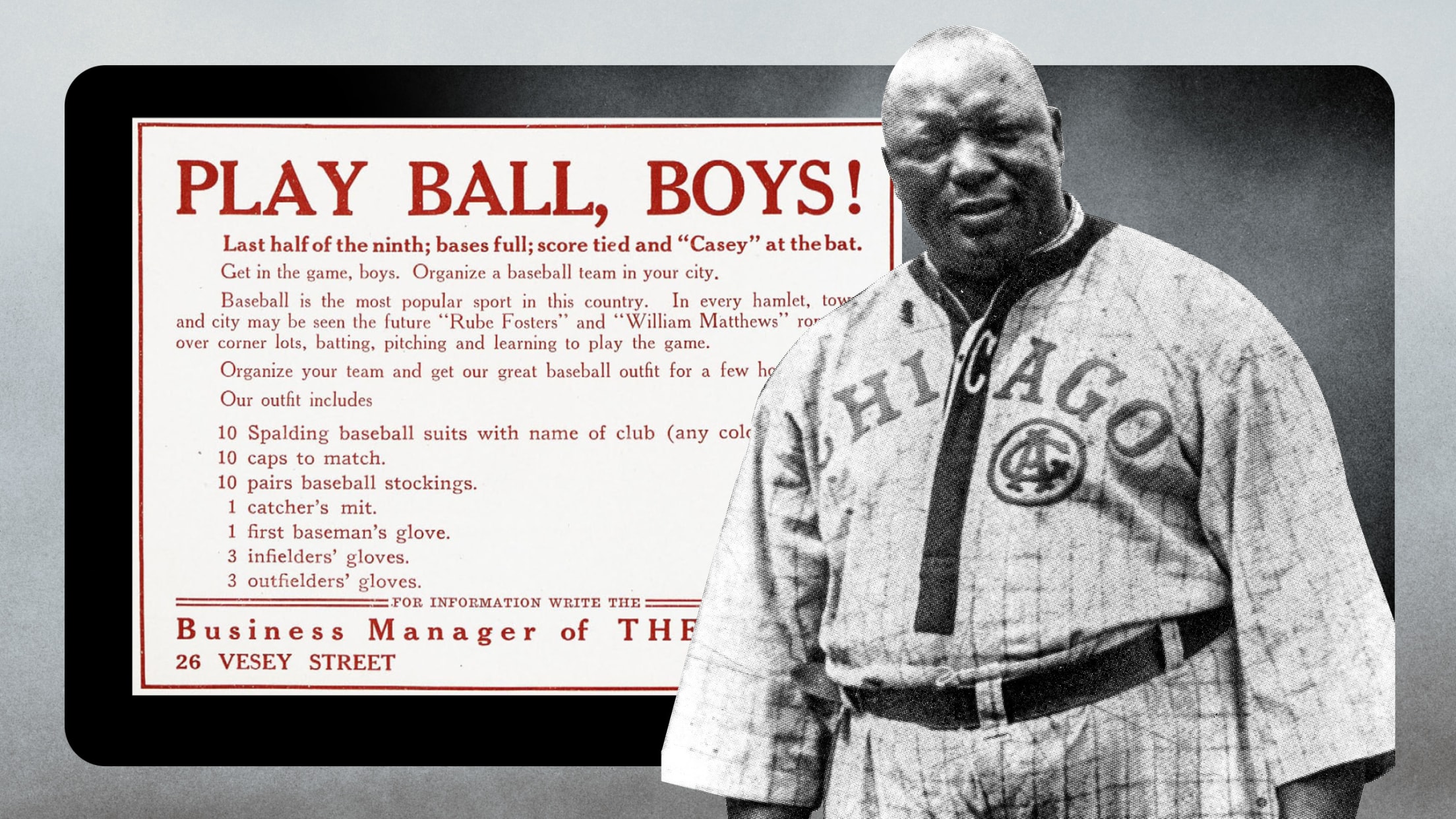

Foster was the first to recognize the absence of the sincere competitive element in these exhibition games. If Negro baseball was to survive and gain the recognition it deserved it had to outgrow the independent, mercenary stage. To achieve this goal, Rube Foster organized the first Negro baseball league in 1920.

It was a six team league with Kansas City, Indianapolis, Chicago, Detroit, St. Louis and the Bacharach Giants of New York comprising the organization. This league enjoys the reputation of having been the most successful operated of the several that have existed since the year of its founding. That success is attributed to the baseball genius and brilliant leadership of Foster who ruled with strict discipline until his death in 1929. Without his astute direction the league passed out of existence the next year.

Inspired by the success of Foster¡¯s league venture in the West and confronted with a loss of colored patronage, eastern owners organized the Eastern Colored League of 1922. This league also consisted of six teams: Hilldale, Brooklyn Royal Giants, Lincoln Giants, Cuban Stars, Bacharach Giants and the Baltimore Black Sox. The Washington Potomacs gained a franchise in 1923 and the Harrisburg Giants became a member one year later. Internal friction over politics caused the league to break up in 1932.

The next league to be formed in the East was the East-West League, which was in reality a reorganization of the Eastern Colored League. This organization lacked competent financial backing and failed to finish the season.

In the distant past colored players have played in certain major leagues. Chappy Gardner, who is better known today as a newspaper writer, but who started playing professional baseball in 1908 with the old Brooklyn Royals and played later with the New York Colored Giants, the New York Stars, Cuban Giants, Havana Red Sox, Quebec Royals, and the New York Red Sox, revealed recently that there are in New York today two former big league players and former club owners and managers.

He cited Sol White, an old timer with an active mind and a head full of baseball brains who was on the West Virginia State League in 1887; played in the Ohio State League (white) and was captain player in the Philadelphia Giants, world colored champs (1901¨C06). White has sat on the bench at the late John McGraw¡¯s request in World Series games to advise McGraw.

Ben Taylor, brother of C.I. Taylor, is also cited by Gardner as having made a record in white and colored baseball in the West.

Perhaps there is, perhaps not, a detailed history of these colorful players of the past. If not, there should be one in the form of a ¡°Hall of Fame.¡±

If the question of admitting colored ball players into organized became an issue, I would be heartily in favor of it.

William E. Benswanger, owner and executive for the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1932-46

The Big League Talk

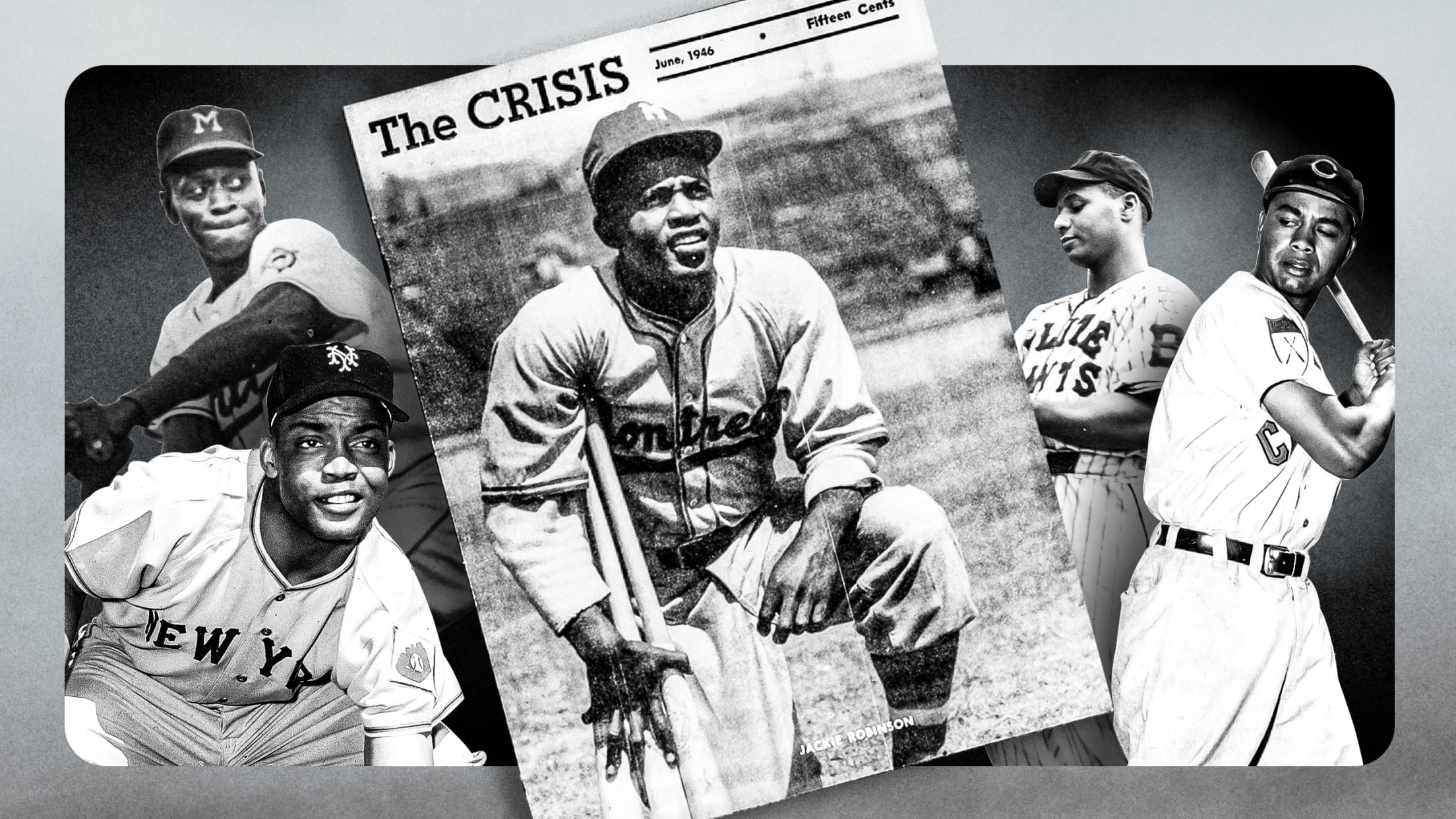

A recent issue in the game which has drawn much attention is possibility of admission of the top players to the major leagues. All colored team owners are not enthusiastic over this project. They point out that, after colored leagues have developed great players, white leagues may take them over and keep all the profit; whereby if they are not so admitted in time colored leagues can pay them as much as they might earn with the whites. It is a widely discussed subject.

Among daily sportswriters who have strongly advocated that a team like the Brooklyn Dodgers could redeem itself by adding a few colored stars are Hugh Bradley of the New York Post, Jimmie Powers of the New York Daily News, and Murray Robinson of the Newark, N.J. Star-Eagle.

Bradley wrote recently: ¡°I suggested that if they (Brooklyn Dodgers) would give some fair consideration to the colored citizens of this nation, they might forthwith discover a means for putting both team and gate receipts into the first division.

¡°Twenty colored players of big time ability ¡ª indeed one or two of them have much of the class of Hubbell and DiMaggio ¡ª are offered to the entire National League.

¡°This is an offer the National League can ill afford to reject. The league gets shellacked in the World Series. The all-star game has become such an absurdity that four Yankees licked the stuffings out of the National League¡¯s best last July.¡±

William E. Benswanger, owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates, said recently: ¡°If the question of admitting colored ball players into organized baseball becomes an issue, I would be heartily in favor of it.¡±

Murray Robinson, writing last week in the Newark Star-Eagle, under the title ¡°Men ¡®Nobody¡¯ Knows,¡± said: ¡°Organized baseball is closed to colored players. Yet we have the word of unprejudiced observers who have followed the performances of the colored stars for years that there are a number of individuals in the ranks of the latter who are as good as any big leaguer.¡±

Leon Hardwick, sports editor of the Afro-American, sums up the attitude of some of the team owners in the league when he says: ¡°At present there is a great move to get colored players into the big leagues. It¡¯s a splendid move and I for one am 100 per cent in favor of it. But, if we had an efficient, workable organization of our own, with all the accompanying publicity it deserves, we wouldn¡¯t have to go begging the white moguls to please let us in.¡±

Must Develop Box Office

On this topic, let the enthusiastic and overzealous colored fan remember that baseball is a big business, void of any sentimentality. The hope of Negro ball players getting into the major leagues does not rest in the development of the individual player, but in the development of our Negro leagues to the point where they will compete with the major leagues for their patrons.

The surest guarantee for stars like Satchell Paige, Josh Gibson, Ray Dandridge, and others to break down the barrier is for them to perform so brilliantly in their own league until fans will leave the white major league parks to come and see them play. Whenever this day arrives, then the Rupperts, the Stonehams, the Rickeys and Wrigleys will be coming to get the attraction that is diminishing their gate receipts.

Let us stop talking of the individual prowess of our colored players ¡ª that is known only too well. For years we have had a multitude of players capable of playing big league baseball, but none of them have been admitted. Let us talk of the Newark Eagles, Elite Giants, Homestead Grays and the rest of our league clubs like white fans laud the Giants, Yankees, Cardinals, and other major league teams. For it is only through the elevation of our Negro league baseball that colored ball players will break into white major league ball. To think otherwise is just sentimentality.

But while widespread discussion is in the air about colored players in the majors, the 1938 baseball season is at hand and the fans are ready. Way down south the Eagles, Crawfords, Homestead Grays, and other teams are already in exhibition competition with their rivals. This training and the opening league games will settle one great question: who is today¡¯s greatest colored pitcher? Is it still Paige, McDuffie, Day, Johnnie Taylor, and others who gained fame in recent years or is there a newcomer somewhere among the rookies who will startle the fans during 1938?