Former sportswriter Bill Simmons, nearly two decades ago now, coined the “Ewing Theory,” a postulate that suggests certain sports teams improve once they lose their best and most high-profile player. (As it says in that piece, the theory actually was invented by Simmons’ friend Dave Cirilli, but no one remembers or cares about that anymore. It’s Simmons’ now and forever.)

The theory has entered the public consciousness so completely that now it’s one of the first things referenced when a star player is hurt or leaves for another team. There are some that even use the theory to tell themselves their team is going to actually improve once their star leaves, a corollary of my own Superstar Fallacy, which notes that fans and media, when they are disappointed with their team’s performance, tend to blame the team’s best player rather than their worst, whose fault it probably actually is.

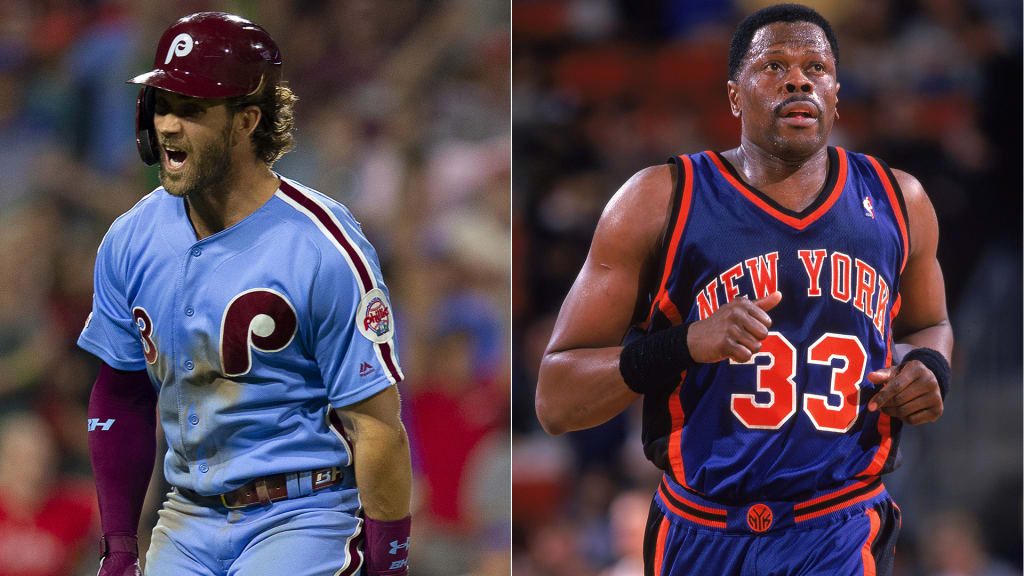

Thus, it was inevitable that the “Ewing Theory” would land on poor Bryce Harper.

Throughout the National League Championship Series, which the Nationals won Tuesday night by finishing off the clearly-ready-to-go-home St. Louis Cardinals, you saw Nationals fans getting creative with their old HARPER jerseys, modifying them to make it known that they were in the NLCS and he was not.

And thus, now that the Nationals have reached the first World Series in franchise history -- leaving just one team left that’s never made one, sorry, Seattle -- Harper is the butt of jokes, with many reminders of his verbal slip at his introductory press conference for the Phillies:

And Harper is supposed proof that the “Ewing Theory” works. Using Simmons’ initial definition of what the “Ewing Theory” is, Harper would seem to fit:

1) A star athlete receives an inordinate amount of media attention and fan interest, and yet his teams never win anything substantial with him (other than maybe some early-round playoff series).

2) That same athlete leaves his team (either by injury, trade, graduation, free agency or retirement) -- and both the media and fans immediately write off the team for the following season.

But -- and here’s where I have to defend Harper, somewhat -- I’d argue that Harper doesn’t fit, and that much of the mockery being hurled in his direction is unfair and unfounded. You can be happy for the Nationals and not be angry at Harper, and realize, even, that this has nothing to do with him at all. Harper doesn’t deserve your Ewing Theory barbs. Here’s why:

1) Harper wasn’t actually the best player on the Nationals.

The whole premise of the “Ewing Theory” is that the team’s star player is the one that leaves, and that everyone writes them off because of it. But Harper was rarely the Nats’ star. Here are the team leaders in WAR (per FanGraphs) every season Harper was on the team:

2012: Gio Gonzalez

2013: Jayson Werth

2014: Anthony Rendon

2015: Bryce Harper

2016: Max Scherzer/Daniel Murphy

2017: Anthony Rendon

2018: Max Scherzer

That’s one year -- one year -- that Harper was the actual best player on the Nationals. Ewing, for what it’s worth, led the Knicks in win shares for eight consecutive seasons. The real question: If Rendon leaves this offseason, will we start using the “Ewing Theory” on him?

2) Harper wasn’t the reason the Nationals lost any of those playoff games.

Another idea of the Ewing Theory is that the player somehow doesn’t “come up big in big games,” which Ewing was always being saddled with. (This was a problem for anyone who played in the Jordan Era. If you didn’t grab the game by the throat like Michael Jordan, you were somehow seen as weak. It was a strange time.) When people bring up that the Nationals never won a playoff series with Harper and now have reached the World Series, the implication is that Harper is somehow the reason.

But this is not true. Harper’s career playoff averages are below his lifetime numbers, but that’s largely because of a terrible NLDS he had in 2012, when he was 19 years old. He went 3-for-23 in that series against St. Louis, though he did have a homer and a triple in Game 5 and would have been the hero had it not been for Drew Storen and Pete Kozma. In the ‘14 loss to San Francisco, Harper had three homers in four games. He had a .458 OBP in the ‘16 loss to the Dodgers, and the reason they lost in ‘17 to the Cubs was because the bats of Rendon (.176 batting average), Trea Turner (.143), Jayson Werth (.167) and Ryan Zimmerman (.150) all went cold. Harper wasn’t the reason the Nationals lost any of those series in the same way he’s not the reason they won them this year.

3) Harper isn’t the reason the Phillies didn’t make the playoffs this year.

The 2019 Phillies had a bummer of a year, with an offseason spending spree that only ended up with an 81-81 record. But Harper more than did his part, leading the team in every major statistical category. He even set a career high in RBIs (114) and hit 35 homers, the second-highest total for him. The Phillies’ problem was injuries to many of their supporting players (including Andrew McCutchen two months into the season, a blow the Phillies never really recovered from) and a starting rotation that was understaffed and underachieving all season. If you’re mocking Harper for watching these games from home, know that he more than did his part to get the Phillies to the playoffs. It was the rest of the team that let him down.

4) The Nationals hardly had some empty cupboard when Harper left, and in fact went out and spent on other free agents.

Simmons emphasizes as a key aspect of the “Ewing Theory” that everyone writes off the team after the superstar leaves it. But no reasonable person wrote off the Nationals in 2019. When MLB.com polled 53 of its reporters prior to the season, 27 of them picked the Nats to win the NL East!

Not only did the Nats still have Max Scherzer, Stephen Strasburg, Juan Soto, Turner and Rendon, they actually splurged on a big free agent this year, bringing in Patrick Corbin, the top pitcher on the market. Did you know that Corbin has actually had a higher WAR (per FanGraphs) than Harper in each of the past two seasons, and is actually earning a higher salary this season ($12.5 million versus $10 million for two backloaded deals). In fact, the average annual values of their respective contracts are quite close ($23.33 million for Corbin, $25.4 million for Harper), which just goes to show that it’s not as if the Nats let Harper walk and pocketed the cash. Their payroll actually went up by about $16 million this year.

Washington got better this offseason, not worse, despite losing Harper. Nobody should be surprised that the Nats did this. They’re really good!

5) The Ewing Theory isn’t actually real.

Yeah, sorry to be the bearer of bad tidings, but the Ewing Theory is one of those ideas that work anecdotally but don’t stand up to actual scrutiny.

Sure, there is the occasional A-Rod leaving the Mariners and them having that 2001 season (though remember they did add Ichiro that winter), Peyton Manning and the Tennessee Volunteers. But it turns out: Stars leaving their teams almost always makes their teams worse.

The Cavaliers collapsed without LeBron James. The Marlins stunk without Christian Yelich and Giancarlo Stanton. The Pirates haven’t been the same since McCutchen left. When Tom Brady retires, the Patriots are going to be just another team.

When we have a moment like the Nats going to the World Series without Harper, we start saying “Ewing Theory!” all over the place. But the Raptors will be worse without Kawhi Leonard this year, and the Nationals will be worse next year if they lose Rendon, and no one will say, “Hey, this should probably prove that the Ewing Theory isn’t a real thing, it’s just anecdotal superstition” even though they absolutely should.

It’s a fun idea. But it’s just a funny made-up notion from a former sportswriter. Leave poor Bryce Harper alone.