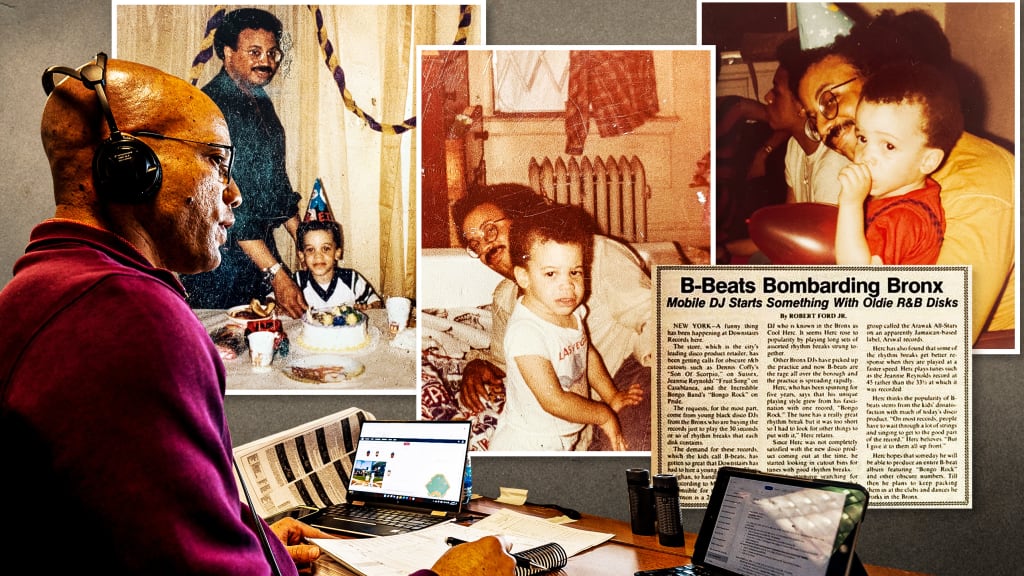

Many years ago, Astros radio play-by-play broadcaster Robert Ford penned an essay about his father, Robert ¡°Rocky¡± Ford Jr., whose decorated career included two distinct acts. He started off as a music writer for Billboard Magazine, and years later, he became a producer for some of the biggest names in hip-hop, just as the musical genre was gaining its footing in the early 1980s.

In 2020, Rocky Ford passed away, and his son -- who will begin his 13th season calling Astros games on the radio this year -- reposted the essay as a tribute to his dad. In celebration of Black History Month, here is a reprint of that essay, which Ford titled ¡°Kids Just Don¡¯t Understand.¡±

When my parents started dating in the mid-1970s, my father wrote for Billboard, the well-respected music business trade publication, covering primarily disco music. According to Dad, he¡¯d started off with Billboard working behind the scenes but, because there were so few Black employees at Billboard at the time and few of the white writers were willing to go into mostly Black venues to cover Black music, Dad got an opportunity to review acts when they performed in New York City.

Not too long before I was born in 1979, Dad had begun moving away from disco and was one of the first journalists to examine the new phenomenon of rap music, which was still mostly confined to the South Bronx. Dad¡¯s first article about rap music for Billboard in 1978 is acknowledged by many as the first mention of the genre in a major print publication.

Dad eventually transitioned from writing about rap to making rap. A chance meeting on a city bus with Joey Simmons led him to his older brother, Russell Simmons, who was trying to get a record deal for Kurtis Blow, a rapper he was promoting. My Dad was able to help Blow sign with Mercury Records, making Blow the first rap act to get a record deal with a major label.

Dad wrote and produced several of Blow¡¯s songs, including his biggest hit, ¡°The Breaks,¡± which came out in 1980. Dad was also a pivotal force behind ¡°Christmas Rappin¡¯,¡± Blow¡¯s first single, which came out in 1979, the year I was born. A Christmas song seems like an odd choice for an artist¡¯s first single, but Dad knew from his days at Billboard that Christmas songs always sell and have the potential to get airplay every year around the holidays (Dad was right -- not a Christmas season has gone by in which I haven¡¯t heard ¡°Christmas Rappin¡¯¡± on the radio at least once).

In the mid-1980s, Dad was able to parlay his relationship with Simmons into a position at the latter¡¯s Def Jam record label. At the time, I was in my first few years of grammar school and not very interested in music. I didn¡¯t have any albums or cassettes, and I rarely listened to the radio on my own. So, it was completely lost on me when I was about 7 or 8 and Darryl McDaniels -- the ¡°D.M.C.¡± in Run-D.M.C. -- asked me if I got good grades and then told me to stay in school (the ¡°Run¡± in Run-D.M.C. is Joey Simmons, who¡¯d helped jumpstart my dad¡¯s career making music several years earlier. These days, Joey¡¯s better known as ¡°Reverend Run¡±).

My parents had separated by then, and I saw Dad mostly on the weekends. On Friday, he would pick me up after school and take me to his spacious office at Def Jam, a few blocks from Manhattan¡¯s SoHo neighborhood. The Beastie Boys used to sit in that office and call Dad ¡°Mr. Ford,¡± which struck me as odd, since most called Dad by his nickname, ¡°Rocky.¡± The fact that the Beasties¡¯ respect for my dad was in sharp contrast to their irreverent, party-animal image was not on my radar.

Dad also worked on several music videos featuring Def Jam artists, so I didn¡¯t find anything unusual when he took me to a warehouse in Queens where a video was being shot for a novice rap duo that called themselves DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince. Dad says I met the pair, but I don¡¯t remember, since I was more focused on the sizeable food spread on the set.

So, that¡¯s all I remember about being on the set of the legendary hip-hop video for ¡°Parents Just Don¡¯t Understand¡± and of my (alleged) meeting with The Fresh Prince -- better known these days by his real name, Will Smith -- who¡¯s gone onto become one of the biggest movie stars of his generation.

Dad also produced several of Kurtis Blow¡¯s albums and moved onto producing and managing several other R&B acts throughout the 1980s and early 1990s.

However, my Dad did work with one rock band, helping them record an album at a studio in New Jersey, where the band was based. I¡¯d often tag along with my Dad to the sessions, passing the time by watching cartoons (most of the sessions I attended were on Saturdays). The band¡¯s shaggy-haired guitarist would play cards with me during his recording breaks. We always played War since I was about 8 years old, and it was the only card game I knew.

War is a simple game that involves little-to-no thought, but the guitarist was always a good sport about playing with me. He would often play while drinking out of a Styrofoam cup -- I don¡¯t recall what was in the cup -- with ¡°ZAKK¡± sloppily written on it in big, black letters. I once asked him about the unique spelling of his first name, and he told me, ¡°That¡¯s the cool way to spell it.¡±

A few months later, my Dad told me Zakk would no longer be playing with the band. He¡¯d moved on to another band, my Dad said, a band I hadn¡¯t heard of. My Dad acted as if it were a big deal that Zakk was with this other band, but I was unhappy about losing my card-playing partner. Years later, I realized ¡°Zakk¡± was Zakk Wylde, and he¡¯d left his obscure New Jersey garage band to perform with Ozzy Osbourne, en route to a very successful career.

It¡¯s funny to look back and think about all the famous musical artists I met as a child and how unaffected I was; other kids my age -- and many adults, as well -- would¡¯ve loved to have the access I had. To me, that access was all part of what Dad did for a living and nothing about it seemed abnormal or cool.

I thought it was cool when Dad played catch with me, or when he took me to the basketball court and showed me how to effectively use the backboard, or when he was able to answer nearly every question I had about whatever sporting event he was watching at the moment.

Over the years, I¡¯ve met the children of many baseball players and coaches, children who get to tag along with their dads in the clubhouse and on the field before games. Sometimes, I wonder what it would¡¯ve been like to have a dad involved in professional baseball; when I was a kid, my access to professional baseball was limited to watching on television and the occasional trip to the ballpark to see a game from bad seats. I would¡¯ve killed to have the access those kids have when I was their age.

But if I grew up accustomed to such access, I probably wouldn¡¯t think of it as a big deal, either. Even though they may be underwhelmed by their dad¡¯s workplace; many children of professional ballplayers and coaches go on to play baseball themselves.

Dad passed away in 2020. I didn¡¯t follow him into the music business, but I¡¯ve grown to appreciate what he did for a living as I¡¯ve gotten older. And, my career in sports broadcasting has similar challenges and benefits to Dad¡¯s career in the music business. We both know what it¡¯s like to work long and unconventional hours, to travel to remote places just to perform our duties and to have our career hang in the balance based on the subjectivity of someone¡¯s ears.

I never had to explain to Dad why I can¡¯t take a lengthy vacation during baseball season, or why I don¡¯t always know when I¡¯ll get home from work, or how it¡¯s both exciting and difficult spending a month away from my family to cover Spring Training.

Dad understood, because he¡¯d been through many of the same things I¡¯ve been through. Thanks to Dad, I know it¡¯s possible to have a demanding, non-9-to-5 career and still make time for my child.

But, man, I really wish I remembered more about meeting Will Smith.