There¡¯s nothing like a great baseball story. But baseball has been around a long time, and in some cases, it can be hard to tell whether those stories are too good to be true. Which is why MLB Mythbusters is here to help -- we'll be diving into some of the game's greatest legends, trying to separate fact from fiction.

Next up: Examining the inspiration for one of America's most iconic poems.

The myth: Which real-life ballplayer served as the inspiration for the mighty Casey in "Casey at the Bat" -- and which real-life town might have inspired Mudville?

The context: By the summer of 1888, Ernest Thayer had just about run out of time.

After graduating from Harvard in 1885 -- magna cum laude, the Ivy Orator of his class -- he'd been expected to go to work with his father, a prominent businessman who owned several textile mills in nearby Worcester, Mass. But Thayer wasn't quite ready to step into his esteemed New England pedigree, so he did what any self-respecting antsy post-grad would do: He moved as far away from home as he could.

One of his classmates just so happened to be William Randolph Hearst -- whose father, mining magnate and soon-to-be U.S. senator George Hearst, had just given him control of a small newspaper, the San Francisco Examiner, as a graduation present. William decided the Examiner needed a humor columnist, and he thought that Thayer -- who'd worked with him at the Harvard Lampoon -- would be perfect for the gig. So Thayer followed his old pal west, and for nearly three years, he churned out satirical pieces under the pseudonym "Phin" (a play on his old college nickname, Phineas).

It couldn't last forever: Eventually, it was time for Thayer to head back home and finally join the family business. But before he did, he decided to file one last column -- a poem, the story of a baseball team from a town called Mudville and the hometown hero who strikes out in his final at-bat. It ran on Sunday, June 3, 1888, in its usual place, inconspicuously sandwiched between some editorials and a weekly column by Ambrose Bierce. It earned Thayer his standard five-dollar fee. And it was given a suitably over-wrought headline: ¡°Casey at the Bat: A Ballad of the Republic, sung in the year 1888.¡±

No one, not even Thayer himself, thought much of it. The New York Sun reprinted the final eight stanzas, but it seemed destined to be forgotten, an amusing if minor bit of cultural ephemera ... until DeWolf Hopper got a hold of it.

Hopper was an up-and-coming comedic actor in New York, performing nightly at a theater in midtown Manhattan. One evening, the management decided to extend an invitation to the New York Giants and Chicago White Stockings, who had just played a game at the Polo Grounds that afternoon. Hopper wanted some fresh material to impress his new audience, so he asked around for ideas, and a friend of his told him he had just the thing: a poem he'd read in the paper a month or so prior, something a room full of big leaguers were sure to love.

Hopper gave it a shot, and an American icon was born:

When I dropped my voice to B flat, below low C, at ¡°the multitude was awed,¡± I remember seeing [Giants catcher] Buck Ewing¡¯s gallant mustachios give a single nervous twitch. And as the house, after a moment of startled silence, grasped the anticlimactic d¨¦nouement, it shouted its glee.

Imbued with Hopper's timing and sense of gravitas, "Casey at the Bat" became a national sensation. He performed it everywhere he went -- over 10,000 times in all, by his own estimation -- and audiences couldn't get enough. Hollywood adapted it into a feature film. T.S. Eliot and Ray Bradbury wrote parodies of it. Mel Allen, the voice of the Yankees himself, recorded it as a children's record. It even became a Disney cartoon.

Casey was now an American icon, Paul Bunyan with a baseball bat, not just a smash but something integral to the country's self-conception. But as the years went by and the poem's legacy grew -- John Fogerty, "The Twilight Zone," an opera -- it begged the question: Just who was Casey, and where did he come from?

The evidence: As you might imagine, just about everybody who'd ever put on a uniform wanted to be known as The Real Casey, and soon enough players from all over started coming out of the woodwork. Foremost among them, naturally, were those actually named Casey (Philadelphia Quakers pitcher Dan Casey even hit the vaudeville circuit after he retired, marketing himself as "The Real Casey").

But nearly all of these claims proved specious, as no one could produce anything substantial tying them to the titular Casey. Even Dan, who claimed that the poem was based on his strikeout to end a game against the Giants on Aug. 21, 1887, couldn't account for how Thayer would've heard that story while living all the way in California -- much less dedicated an entire poem to it almost a year later.

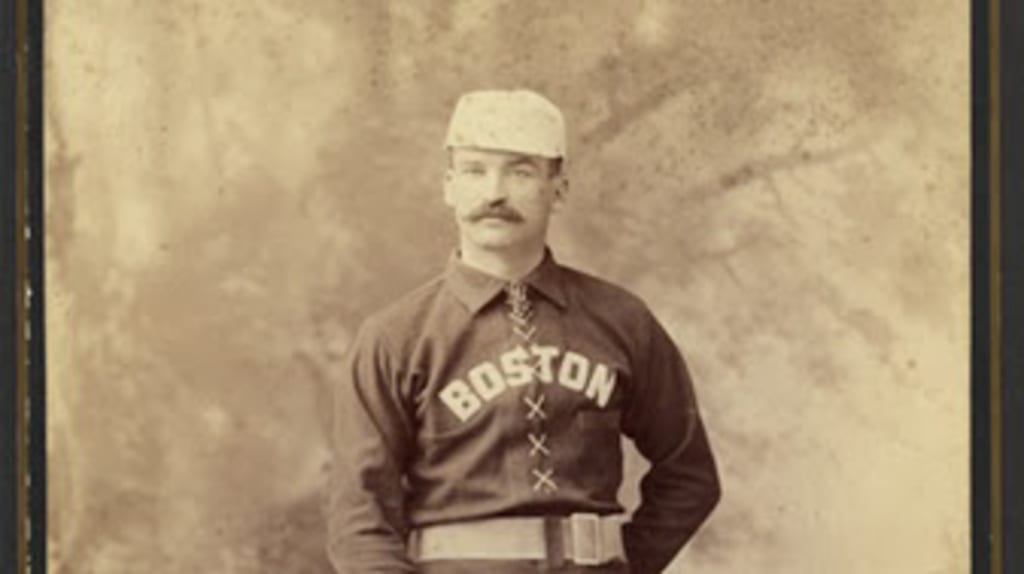

One big leaguer, though, did manage to make a pretty compelling argument, so much so that he's probably the real-life figure most closely associated with Casey. Mike "King" Kelly seemed to check all the boxes: He spent six years playing in Boston, Thayer's backyard, and Thayer allegedly covered him during an offseason promotional tour in San Francisco; he was a larger-than-life figure, known as "$10,000 Kelly" for the record sum he commanded from the Boston Beaneaters; and he was Irish, just like Casey.

The poem doesn't give us much to work with, but the few details it does provide -- "There was ease in Casey's manner as he stepped into his place;/There was pride in Casey's bearing and a smile lit Casey's face." -- seem to suggest that he was a man known for his panache, which would jive with a man who became a vaudeville star in the middle of his playing career.

So what's the problem? In 1935, Thayer finally broke his silence to the Syracuse Post-Standard, and he pretty emphatically blew up Kelly's spot:

The poem has no basis in fact. The only Casey actually involved, I am sure about him, was not a ballplayer. He was a big, dour Irish lad of my high school days. While in high school, I composed and printed myself a very tiny sheet, less than two inches by three. In one issue, I ventured to gag, as we say, this Casey boy. He didn¡¯t like it and he told me so, and, as he discoursed, his big, clenched, red hands were white at the knuckles. This Casey¡¯s name never again appeared in the Monohippic Gazette. But I suspect the incident, many years after, suggested the title for the poem. It was a taunt thrown to the winds. God grant he never catches me.

So there you have it. According to the man himself, Casey has no real-world analog -- not Kelly, not anybody else. He's simply a composite figure, named after an old high school nemesis as a light-hearted gag.

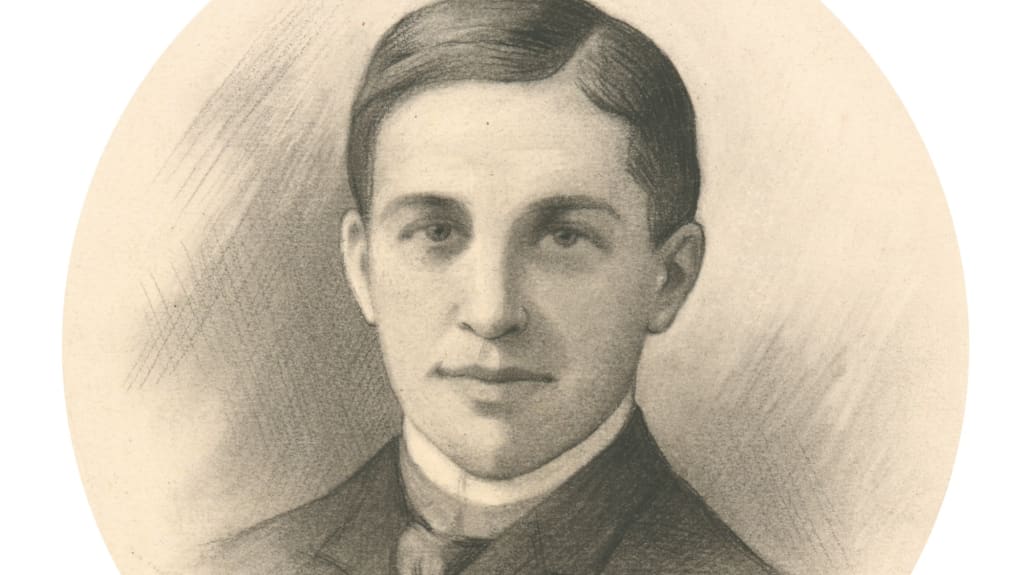

But there's one more theory worth mentioning. Before he got around to setting the record straight, Thayer dropped what might be a hint: "The verses owe their existence to my enthusiasm for college baseball," he told the Post-Standard, "not as a player, but as a fan." So, if the poem got its inspiration from the college game, why not Samuel Winslow -- the captain of Harvard's baseball team in 1885, and a close friend of Thayer's?

The Crimson went 27¨C1 and won the Intercollegiate Baseball Championship in Winslow's senior year. And he was, by all accounts, a strapping man: Just take a look at this photo, taken during his time as a Congressional representative from Massachusetts' fourth district.

Looks an awful lot like Kelly -- not to mention the popular image of the mustachioed Casey. And there's more: According to a 2008 auction catalog, Hopper "met Thayer in the early 1890s while performing in Massachusetts and asked him who the inspiration for Casey was. Thayer replied that it was his old Harvard pal, Samuel Winslow.¡±

The verdict: Many men have claimed to be Casey in the more than 100 years since the poem first captivated the country. Most of those claims can be disregarded. This really boils down to three options: Is it Kelly, is it Winslow, or is it nobody in particular?

If it really had been based on Kelly, why wouldn't Thayer have just admitted it? He never thought much of his most famous work, even allowing Hopper to continue using it without paying him royalties, so it's safe to say that pride wasn't a factor. And while he eventually gave an ostensible explanation, read it again: He suspects that the incident suggested the title for the poem, an incident that just so happens to make for a pretty amusing story.

Sure, he covered Kelly for a couple of days one winter, but it seems most likely that, when Thayer let his imagination run wild on the diamond, it thought of Winslow: the hero of his college years, a man with burly bravado to spare, a man who seemed to channel all of the things that made Casey, well, Casey.