The Dodgers in 2025 plan to use a six-man rotation, both because of how many of their pitchers are coming off injuries, and because thatˇŻs how Shohei Ohtani and Yoshinobu Yamamoto operated in Japan.

The Red Sox may do the same ¨C though Lucas Giolito doesnˇŻt sound like he cares for it. The Mets are likely to utilize it as well. Surely others will follow at various points, if not for the full season, just like the Orioles (2024), Nationals (2023), Mariners (2023), Phillies (2023), Astros (2022), Mariners (2021), Angels (several times) and many others have done recently.

Maybe that sounds counterintuitive. After all, does it make sense that, at a time when teams are having a hard time keeping pitchers healthy, that some would move to a model that requires more starters? So it's probably worth explaining, because itˇŻs not a trend thatˇŻs going to come out of nowhere in 2025. In some ways, itˇŻs actually already in progress. Consider this:

- In 2021, for the first time ever, there were more starts on exactly five days of rest (37%) than four (33%).

- In 2023, it happened again. (41% to 33%)

- In 2024, it happened again. (42% to 32%)

Why? ThereˇŻs no shortage of theories. Maybe more rest keeps pitchers healthier; maybe more rest makes them more effective; maybe having more starters takes stress off the bullpen; maybe you have enough starters that youˇŻd rather not throw any out of the bullpen; maybe some ˇ°startsˇ± are in reality just ˇ°bullpen games,ˇ± and so forth. These are all compelling theories, albeit none really proven out.

Maybe itˇŻs all of those, to some extent. But weˇŻd also argue another theory, too: ItˇŻs connected in some part to how much baseball needs to be played in a season, and how much time passes between those seasons. Don't forget that for the first 60 years of the 20th century, teams played 154 games and then went directly to the World Series, on eight different occasions starting the Fall Classic before September even ended.

For example: When Willie MaysˇŻ 1954 Giants won the ring with a World Series sweep, they played a total of 158 games, combining regular season and postseason. The last game was on Oct. 2, giving them 193 days off before the next yearˇŻs April 13 opener.

The 2024 champion Dodgers, however, had to play 178 games, with a month of expanded playoffs atop a 162-game regular season, and theyˇŻll get only 139 days off before starting this season against the Cubs in Tokyo (or 148 days before domestic Opening Day on March 27, for a fairer comparison).

Put it this way: Those 1954 Giants threw 1,427 total innings. The 2024 Dodgers threw 1,582 2/3, and theyˇŻll get 54 fewer days off to recover from them.

When contenders look ahead to the 2025 season, then, theyˇŻre not just planning for 162 games. They're also planning for the possibility of four rounds of playoffs, depending on if they get the bye and how far they advance. These are rounds, before the World Series at least, that legends like Sandy Koufax never had to worry about.

If all of those rounds went the distance, that could be 22 extra games, or nearly 200 additional high-stress innings, with considerably less time for those arms to rest. (That's to say absolutely nothing of other changes in the sport, which including the DH replacing pitchers batting, the ability of nearly every batter to hit a home run today, and every pitcherˇŻs all-out chase for velocity and spin.)

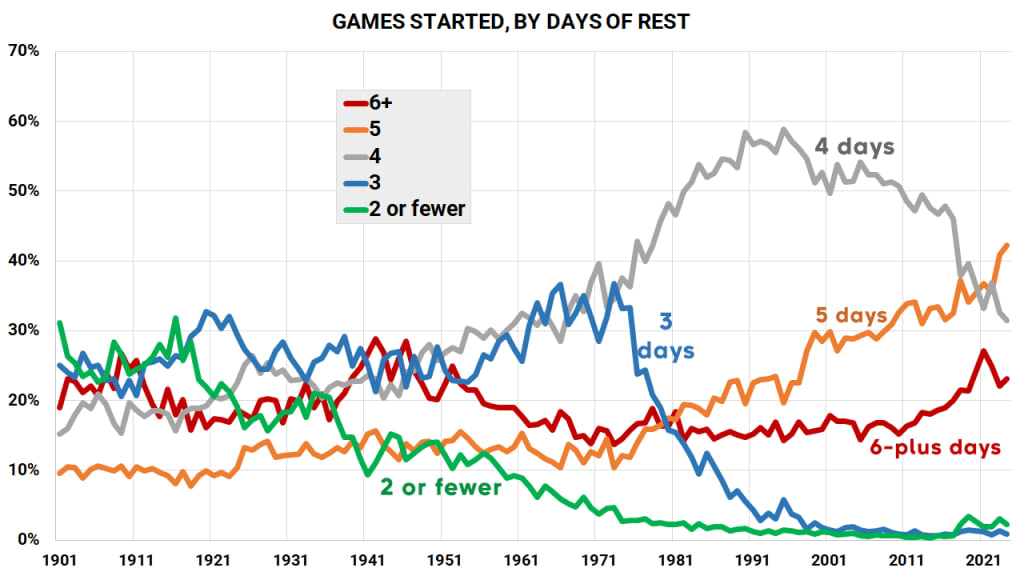

In order to explain whatˇŻs coming, letˇŻs talk for a moment about how we got here. This graph, showing the share of starts based on how much rest the starter had, tells you a whole lot about how baseball history has worked. Up until 1960, it's a total mess, and that's even excluding the barely-the-same-sport era of the 19th century, when some teams had two-man rotations or occasionally even one lone starter all year long,

For most of the first half of the 20th century, making a start on five days' rest, which is what youˇŻd get from a regular six-man rotation, was rare, comprising only around 10% of starts. In the earliest days, making starts on two days' rest was most common, but but for decades, starts were relatively evenly divided between everything else aside from five days' rest ¨C two, three and four days, plus six or more.

Of course, itˇŻs somewhat difficult to compare directly, because the idea of a ˇ°starting rotationˇ± was quite loose in the early decades of the game, and some of that was necessitated by regular doubleheaders, anyway ¨C itˇŻs rare that a team has to staff two starting pitchers in one day these days. Still, you might be surprised to learn that, say, the champion 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers had seven starters make 10+ starts and had just one top 200 innings before using six starters in seven World Series games, but they did. Not every classic team had four 350-inning beasts, contrary to popular belief.

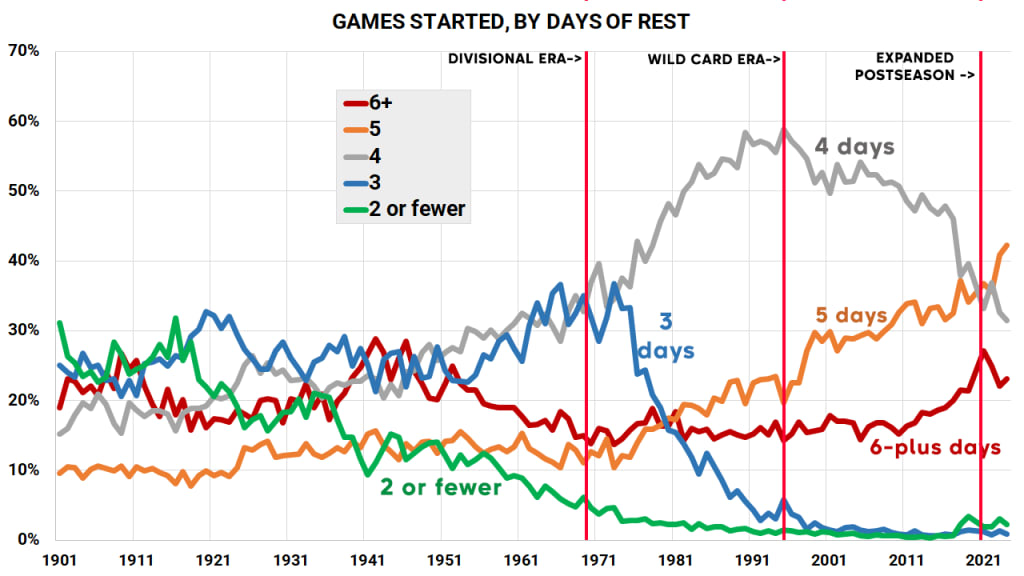

Now, letˇŻs show you the exact same chart, but with some pretty important moments in baseball history included.

It's not hard to draw some connections.

When did the idea of starting pitchers regularly on two or three days of rest die?

In the mid-1970s, as the sport had expanded from 16 teams (1901-ˇŻ60) to 24 teams (starting 1969), with the regular-season schedule jumping from 154 games to 162, and with an extra round of playoffs coming into play in '69. (The League Championship Series, at first five games, later expanded to seven.) ThereˇŻs a reason no pitcher has started even 38 games in a season in nearly 40 years, and thatˇŻs because the once-popular four-man rotation became a five-man rotation.

When did the five-man rotation trend away from dominance?

A little around the turn of the century, as four teams were added in the 1990s and the Wild Card was added in '95. But it dropped below 50% of starts for the first time in decades just as the second Wild Card was added in 2012.

When did four days of rest stop being the primary choice?

Right around when the postseason expanded to a 12-team field. It's not that the trend hadn't already been in place for years, but this is the inflection point.

So: Does it work, or does it not? Does it matter? Despite a number of studies ¨C hereˇŻs FiveThirtyEight in 2015, and Russell Carleton of Baseball Prospectus the same year, and FanGraphs in 2021 -- itˇŻs extremely difficult to say.

One anecdotal piece of evidence in favor is that the extra day of rest better mirrors what other high-level baseball leagues do. As we know, in Japan, starters go once per week. ItˇŻs not just there, though.

When MLB released findings from a report on the pitching injury problem last month, one aspect that was noted was that Minor League starters generally get more rest than Major Leaguers do. Last year, just more than 10% of starts in the Minors came on five days rest or less, and as one anonymous former Major League pitcher noted, ˇ°a phenom will come up and youˇŻre putting him into a five-man rotation, whereas in the Minors he pitched every sixth day.ˇ±

In college, the role of ˇ°Friday night starterˇ± is one of pride, given to the teamˇŻs presumed ace. But itˇŻs more than just a title, too; Friday starters tend to pitch on Fridays, and thus once a week. Take a look at 2024 National League Rookie of the Year Paul SkenesˇŻ game log from his final season at LSU, in 2023. He made 19 starts that year for the Tigers, and the first 18 all came on six, seven or eight days rest. The only one that was shorter rest was the final one, which was still on five days rest, and even that was because by that point, LSU was deep into the College World Series ¨C which they would end up winning.

When Skenes joined the Pirates last year, each and every one of his starts came on five days' rest or more, which at least in this one particular case aligns with the idea of "use pitchers in the Majors like they were used at lower levels." It's also exactly why you canˇŻt just look across the Majors to see if starters overall did better or worse on more rest, because now youˇŻre looking at different groups and different talent levels ¨C all of SkenesˇŻ high-quality starts fall into one bucket, which skew the results.

It makes anecdotal sense that having pitchers come to the highest level of competition and asking them to do something different than theyˇŻve done in the past might not be ideal, but again, this is mostly anecdotal.

YouˇŻll have then-Astros GM James Click in 2022 saying that ˇ°hopefully we can lengthen them and continue to get more innings out of them and take some of the stress out of the bullpen,ˇ± and youˇŻll also have Phillies manager Rob Thomson pointing out that ˇ°one thing about a six is it taxes your bullpen because youˇŻre one man short.ˇ± Neither is really wrong, and you have to account for the fact that in 2021, the 25-player roster expanded to 26, and thereˇŻs just a lot of moving pieces here.

Plus, thereˇŻs more than one way to do a six-man rotation; it doesnˇŻt mean that all six starters all pitch on five days' rest, or at least it doesnˇŻt have to. It might mean that your top starter or two sticks on four days' rest ¨C maybe this is what Giolito lands on ¨C and everyone else goes on five days. And, of course, thereˇŻs more than a few teams who can barely even find five starters, much less six.

It wonˇŻt spread to all 30 teams, not any time soon, and probably not ever. There will always be pushback, like when Cole Hamels said in 2018 that ˇ°it's not part of baseball ˇ I was brought up in the Minor Leagues on the five-man, and that's what I'm designed and conditioned for.ˇ± Of course, itˇŻs not hard to imagine that starters in the 1970s, used to pitching every fourth day, pushed back on going to every fifth day, too.

The teams that use it might choose to do so across particular stretches of the season where off-days are rare and pitchers are healthy. It might not just be a curiosity, either. The four-days-of-rest start, for decades a given as the norm ¨C even if not always the same five pitchers consistently ¨C hasnˇŻt been the primary method of pitching in three of the last four years. It might not be in 2025, either.

But if you're wondering why there's more starters on more rest, there's at least one obvious answer to point to: There's more baseball.