DJ LeMahieu is headed off to free agency, and it's not surprising to note that he is going to be a highly-valued player. In two years with the Yankees, LeMahieu hit .336/.386/.522, a 145 OPS+, while also adding value by moving around between three infield spots. He finished fourth in American League MVP voting last year, and it's highly likely that he will do well in this year's balloting when it's announced on Nov. 12, too. He's been one of baseball's dozen most valuable players in 2019-20.

This isn't a story about how good LeMahieu is (very), or where he'll fit the best (anywhere). It's not even a story about ignoring his admittedly-massive home/road splits in cozy Yankee Stadium. (Do recall that two years ago we had to have exactly the same conversation, that time pointing out that his poor stats away from Coors Field didn't predict problems with the Yankees. We'd say that one worked out.)

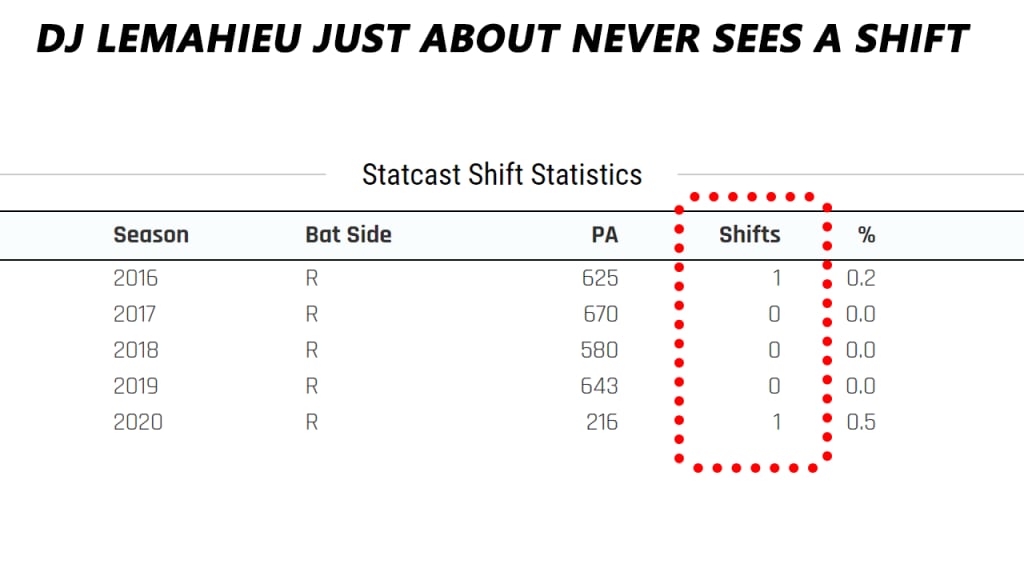

No, this is a story about the skill LeMahieu brings that no other hitter in baseball can match: In a world where everyone is being shifted more and more, LeMahieu is baseball's most un-shiftable man. (A "shift" is defined as "three infielders to one side of second base.") Just take a look at his Baseball Savant player page:

Two plate appearances ending with a shift! In five years! Think about that. It's wild, especially when you realize how many hitters see two shifts in the span of two plate appearances these days. Except ... it's not two, not really. It's zero, at least in plate appearances that don't come with enormous caveats. Let's show why.

Here's the plate appearance in 2020 that came with the shift on, and you might not recognize the Toronto pitcher. That's because he's not a pitcher. He's rookie backup infielder Santiago Espinal, who came on to mop up in a blowout; the score was 19-3 at this point.

That soap bubble Espinal threw was a mere 48.7 MPH, making it the slowest pitch ever tracked hit for a home run. This was technically a shift because the second baseman was standing just ever so slightly on the left side of second base, but it's pretty clear that when you have a rookie infielder throwing 48 MPH softball lobs, you're going to come up with a softball defense. This doesn't feel like it it's in the spirit of "being shifted."

So it's safe to say that's not a "regular" plate appearance, and neither, as it turns out, was the 2016 one. That was an intentional walk issued by Mets pitcher Jerry Blevins -- back in the olden days when pitchers actually threw those pitches -- where the second baseman was standing, doing nothing, really, to the left of second base. That doesn't seem to count either.

The last "real" shift we could find came back on July 18, 2016, when the Rays did it to him for a handful of pitches in Coors Field. That's it. That was over four years ago. In case you're wondering how all of this ranks, let's dig up the active hitters who have seen at least 2,500 pitches over the last five seasons. (For this, we stripped out the intentional walk pitches.)

Lowest percent of pitches with a shift on, 2016-20 (active players)

0.0% -- LeMahieu

0.1% -- Dee Strange-Gordon

0.1% -- Miguel Rojas

0.2% -- Isiah Kiner-Falefa

0.2% -- Jean Segura

0.2% -- Chris Owings

0.2% -- Christian V¨¢zquez

0.2% -- Orlando Arcia

0.2% -- Travis Jankowski

LeMahieu basically rounds down to zero. Among the other hitters listed here, no one is near the quality of batter LeMahieu is.

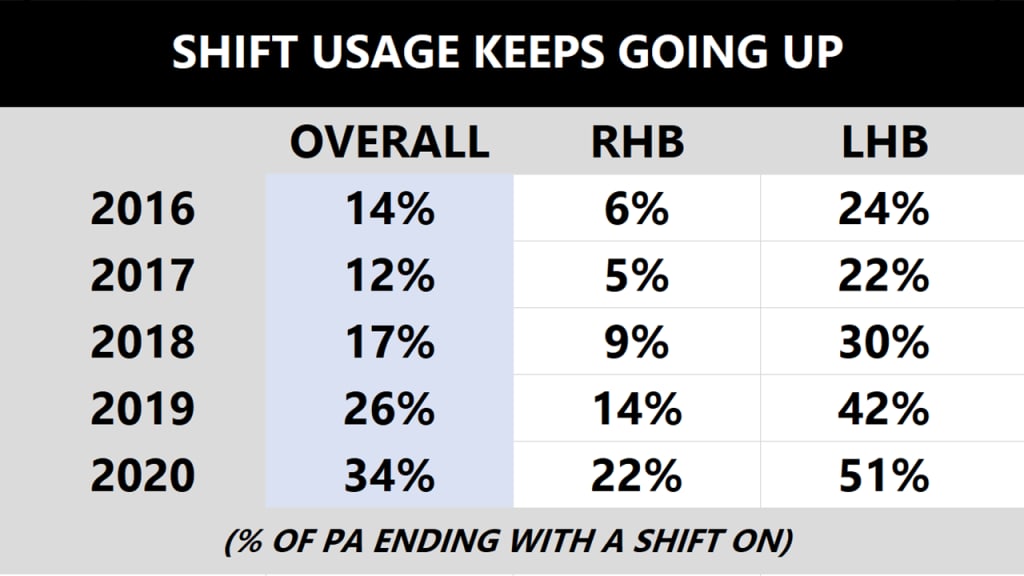

So, it goes without saying that what LeMahieu is seeing is not at all what the rest of the Majors are seeing. For example: a hitter like Joey Gallo saw more than two shifts in a game 55 times this year alone, and Gallo played in only 57 games this year. While Gallo is an obvious outlier, it's obvious that shifts have become more and more normalized, and not just against lefty hitters.

Or, to put that another way: Over the last five seasons, Major League hitters have seen 597,628 pitches with an infield shift on. Righty hitters have seen 192,030 of those pitches. LeMahieu has seen seven. As everyone else is getting shifted more often, LeMahieu simply is not. (In the infield, anyway. Entertainingly, LeMahieu has been the subject of some of baseball's most extreme outfield shifts.)

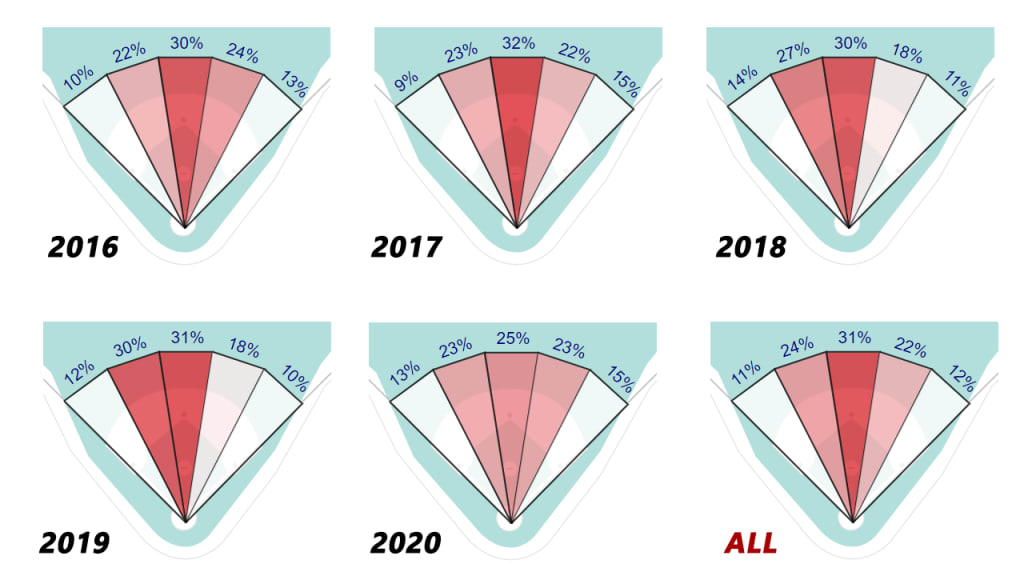

So what makes LeMahieu the outlier? It's not all that hard to figure out. Over the last two years, no hitter who has taken at least 500 plate appearances has a lower pull percentage than LeMahieu does. No hitter goes to the opposite field more than LeMahieu does. If you think about a shift being used against a player who pulls everything on the ground constantly, that's not LeMahieu, as these yearly charts of where he puts the ball (on balls that did not go further than 200 feet, so not including outfield here) will show.

That's a whole lot of batted balls up the middle, isn't it?

Now, what's interesting here is that if anything, these charts might indicate an argument that LeMahieu should be shifted more. Or, perhaps, not "shifted" so much as "it might be a good idea to have an infielder playing behind second base," whether that gets qualified as a shift or not. After all, he does have a Top 10 Batting Average on Balls in Play (BABIP) of qualified hitters over the last five years, and he's not exactly known for his blazing foot speed.

Then again, recent research from analysts like MLB.com's Tom Tango and Baseball Prospectus' Russell Carleton suggests that we're already seeing the point of too many shifts on righties as it is: that the shift isn't necessarily having the effect that people think it has, which necessarily leads to the understanding that banning the shift wouldn't have the effect people think it might, either. (It wouldn't cut down strikeouts or likely put more balls in play.)

LeMahieu, for what it's worth, is one of the many good arguments against any attempts to ban the shift. Aesthetically, LeMahieu seems like exactly the type of hitter that people want to see, the kind who makes lots of contact and foils the shift. Banning it wouldn't affect him much, but it would certainly give more value to the Chris Davis type of strikeout-prone lefty slugger, the type that seems to be out of favor, at least in entertainment value. Is that what we really want? Another way of saying that is: Don't like the shift? Don't ban it, render it ineffective, the DJ LeMahieu way.

As he told MLB.com in 2017, "I try to just block it out, hit the ball hard. If they're there, they're there. Hopefully, they're not."

Given how often we've talked about the fact that one of the main purposes of the shift is simply to convince hitters to be someone they're not, that sounds pretty good to us. It's likely going to sound pretty good to whichever team is fortunate enough to sign him this winter, too.