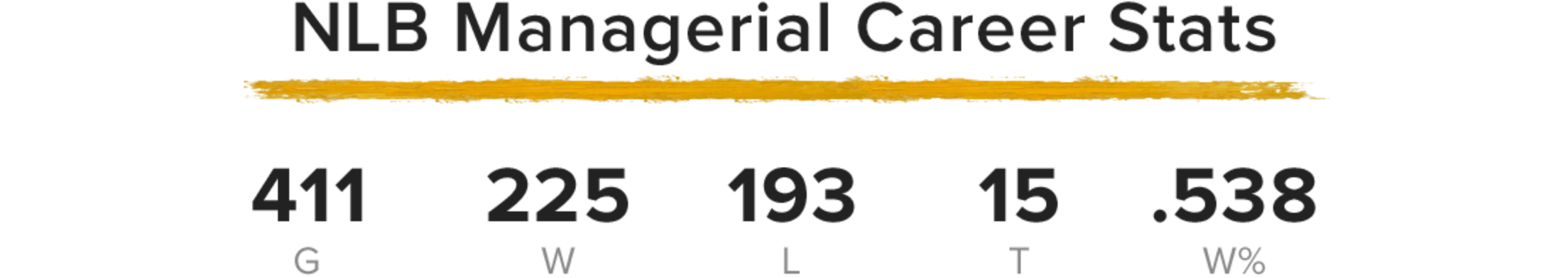

Records of Negro Leagues Baseball statistics are incomplete. The above was compiled using various sources including the Negro Leagues Database at seamheads.com after consultation with John Thorn, the Official Historian for MLB, and other Negro Leagues experts. In December 2020, MLB bestowed Major League status on seven professional Negro Leagues that operated from 1920-48. MLB and the Elias Sports Bureau are in the process of determining how this will affect official MLB records and statistics.

Posey was peerless in Negro Leagues lore

By: Shakeia Taylor | @curlyfro

¡°Sometimes a brilliant athlete soars like a fiery skyrocket and spreads his name in glittering letters across Sportdom¡¯s lofty skies.¡± -- Ches Washington on Cumberland Posey, The Pittsburgh Courier, April 6, 1946

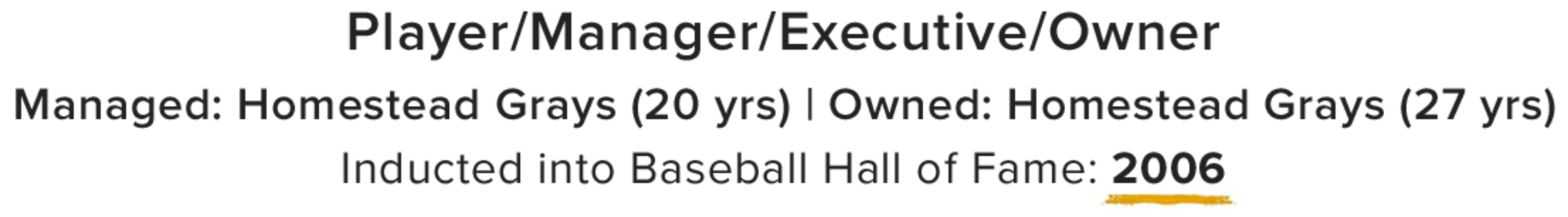

The only person to be inducted in both the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame and the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cumberland ¡°Cum¡± Willis Posey, Jr. is regarded as one of the greatest athletes of his era and a legendary entrepreneur; he was voted into the baseball Hall as a pioneer/executive.

For thirty-five years, Posey was one of the most influential men in baseball. He knew the sport inside and out, having been at nearly every level at some point in his career. Posey was a player, manager, owner, executive and league officer.

Born June 20, 1890, to Cumberland Willis Posey Sr. and Angelina "Anna" Stevens Posey in Homestead, Pa., Cum was their youngest son. Homestead, an integrated suburb of Pittsburgh, was booming due to Carnegie Steel Corporation¡¯s growth. Posey Sr, the son of freed slaves, is believed to be the first African-American to receive an engineering license in the United States. He got his start as a deck sweeper on a ferry boat and eventually founded his own shipbuilding company -- Posey Steamboat Company. Anna, a teacher from Ohio, was the first African-American to graduate from as well as teach at Ohio State University. In addition to his other businesses, Cum Posey, Sr. was one of the original investors in the historically Black Pittsburgh Courier newspaper, where Posey Jr. later wrote regular columns called ¡°Pointed Paragraphs¡± and ¡°Posey¡¯s Points.¡±

Posey Jr. always loved sports. At 5-foot-9, 145 pounds, he was described as small, agile and quick, scoring the majority of his points in basketball around the perimeter. In 1908, Posey Jr. led Homestead High to the city championship and played basketball at Penn State for two years. One of the best basketball players in the East; he was Penn State¡¯s first Black student athlete. Along with his brother, Seward, and some friends, Posey Jr. organized the Monticello Athletic Association basketball club, also known as the Monticello-Delany Rifles -- a team that held the consensus national Black championship for five years. The team changed its name to the Loendi Big Five in 1913 in recognition of its sponsor, the Loendi Social and Literary Club. Posey Jr. was not only the organizer, but the team¡¯s star player.

In 1915, Posey Jr. was enrolled under the name ¡°Charles Cumbert¡± at the Pittsburgh Catholic College of the Holy Ghost, now called Duquesne University. There, he continued his basketball stardom, leading the team in scoring for three consecutive seasons. He was also captain of the golf team.

Posey, Jr. was a player, manager and owner in the Negro Leagues. He began his career in 1911, playing outfield for the Homestead Grays. In '16 and '17, he became captain and field manager, respectively. Due to his experience organizing games for his basketball team, Posey Jr. started booking games for the club. By the 1920s, he had become owner of the Grays.

Around this time, Rube Foster¡¯s Negro National League was formed in the Midwest. Posey Jr. opposed organized baseball, viewing barnstorming as more lucrative for the team. Raiding other ballclubs for talent, the Grays were a dominant independent baseball club, beating many Black and white baseball teams alike.

Known for having a fiery personality. Posey famously pulled his team from the field in front of 10,000 fans in New York, forfeiting the game, because he disagreed with a call by an umpire. It was July 1928, in the bottom of the ninth, and Homestead was beating the Lincoln Giants, 11-8, when the momentum of the game shifted on a series of plays. The Chicago Defender described the story:

¡°Scales opened with a double. Mason hit for two sacks, scoring Scales, and Lewis lined safely into right, carrying Mason over the platter. Rojo bunted down the first base line and ¡°Lefty¡± Williams with a quick recovery, made a rifle shot peg to Beckwith for a force play on Lewis. The ball, from any angle of the field, beat the runner to the bag, but that is not the point, as Umpire Seixas, who was on top of the play, declared the runner safe, insisting Beckwith did not have his foot on the bag. Hence Cum Posey considered a sport in baseball circles, flared up in a temperamental outburst and ordered his club from the field.¡±

A year later, having moved up in the ranks of Black baseball, Posey retired from playing and focused his energy on the business of owning the team, joining the American Negro League, which quickly folded.

The Grays became a member of the second Negro National League in 1935. In February 1938, Posey was selected to be the secretary-treasurer of the league. Under Posey¡¯s leadership, the Grays won nine consecutive pennants and eight out of nine Negro National League titles from '37-45. Considered a model franchise, other teams borrowed from both the playing and management style of the Grays. Over a dozen Negro Leagues Hall of Famers played for the team, including Cool Papa Bell, Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, and Ray Brown -- who also married Posey¡¯s daughter, Ethel.

Nancy Boxill, Posey¡¯s granddaughter, told Jesse Washington of The Undefeated Posey had been talking with Dodgers president Branch Rickey about the best way to integrate the game. He passed in April 1946 without ever getting to see that come to fruition. After learning of Cumberland Posey, Jr¡¯s passing, Gus Greenlee, owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, expressed his grief to the Pittsburgh Courier, saying, ¡°Negro baseball suffered a severe loss in the death of Cum Posey. Few men have played a more important role in the development and organization of Negro professional baseball. Although at times we opposed each other bitterly, I always held the greatest respect for Cum as friend, associate and rival. There will never be a figure to replace the militant Cum Posey in the world of sports.¡±

Shakeia Taylor is a freelance baseball writer who has a special interest in the Negro Leagues and women in baseball. A 2020 SABR award nominee, her work has appeared in Fangraphs, SB Nation and Baseball Prospectus.