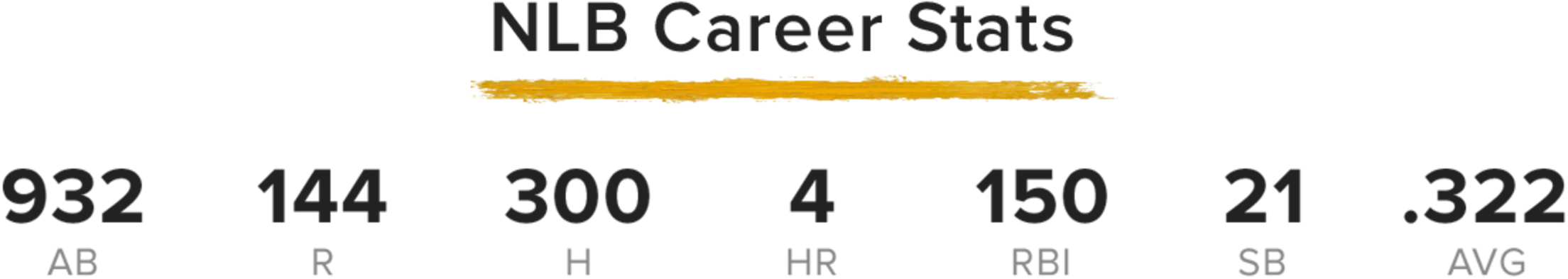

Records of Negro Leagues Baseball statistics are incomplete. The above was compiled using various sources including the Negro Leagues Database at seamheads.com after consultation with John Thorn, the Official Historian for MLB, and other Negro Leagues experts. In December 2020, MLB bestowed Major League status on seven professional Negro Leagues that operated from 1920-48. MLB and the Elias Sports Bureau are in the process of determining how this will affect official MLB records and statistics.

Best 3B To Never Make the Majors

By: Sarah Langs | @SlangsOnSports

Ray Dandridge never got to make his mark on the Major Leagues, but his imprint on baseball history as a whole is undeniable.

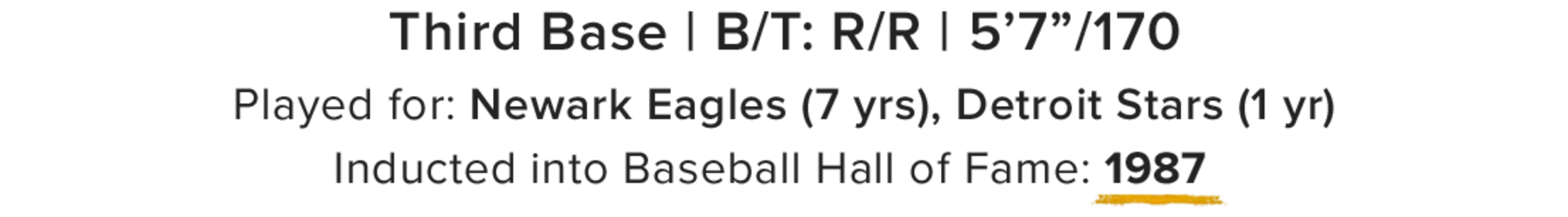

Considered the best third baseman to never make it to the Majors, Dandridge began his professional career in the Negro Leagues as a 19-year-old and played until he was 41, in an independent baseball league. His primary Negro Leagues team was the Newark Eagles, but his Negro Leagues career included multiple stops before he moved on to play for Mexico City and Veracruz in Mexican Leagues. He played in the Minors for the Giants but never got the call.

We¡¯ll never know what Dandridge could have done playing in the Majors, but his legend lives on through stories, photos, stats and accolades.

Here are some key points to know about Dandridge, who was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1987.

? Dandridge is considered by many to have been the best defensive third baseman in the history of the Negro Leagues, if not baseball history as a whole. He was bow-legged, but that didn¡¯t affect his fielding ¨C very few balls got past him. His Hall of Fame plaque dubbed him a ¡°Flashy but smooth third baseman. Defensively, a brilliant fielder with a powerful arm.¡±

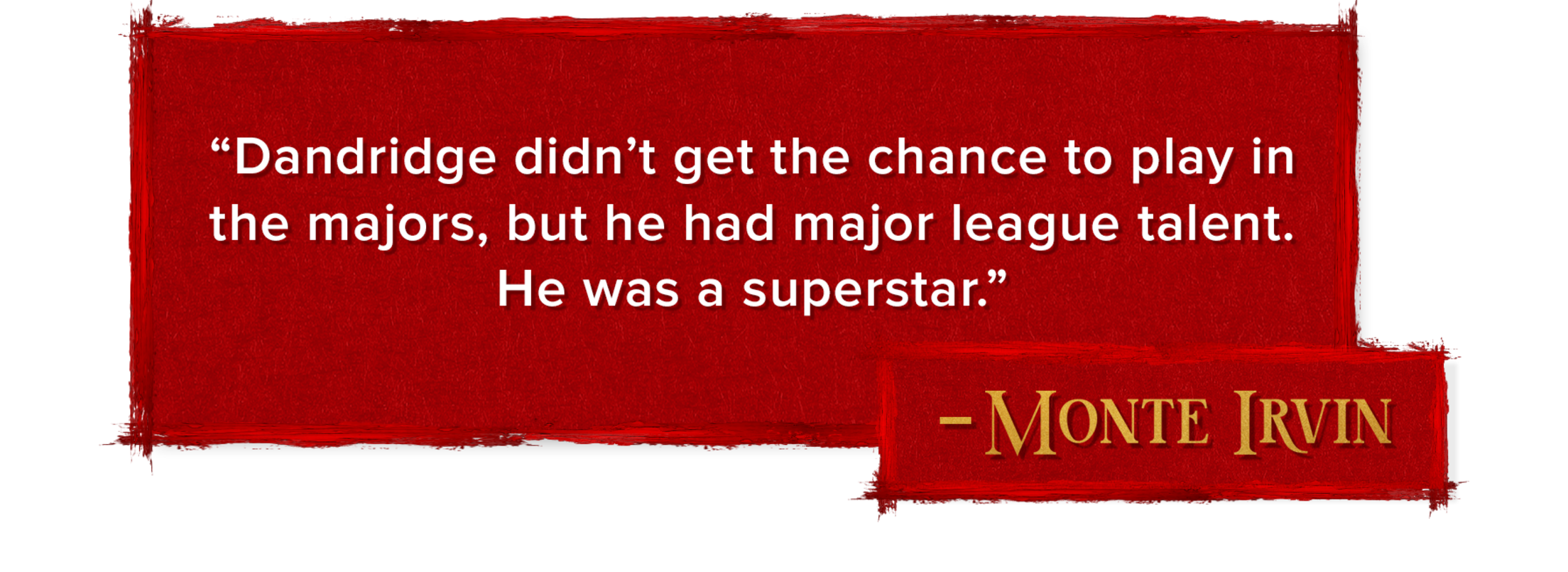

¡°He was a born third baseman but could play second and short equally as well,¡± Hall of Famer Monte Irvin, who was teammates with Dandridge on the Newark Eagles, once noted. ¡°He had the quickest reflexes and the surest hands of any infielder I¡¯ve ever seen. In a season, he had a bad year if he made four errors. As a third baseman, he could field the swinging bunt and get the runner at first better than anyone. It was a thing of beauty and worth the price of admission just to see him make that one particular play.¡±

Dandridge spoke about how much he studied the game and his idols, including Judy Johnson, who is considered the other all-time great Negro Leagues third baseman. Dandridge credited Jud ¡°Boojum¡± Wilson for helping turn him into the defensive standout he became, teaching Dandridge to charge the ball more aggressively.

¡°I used to listen to oldtimers,¡± Dandridge once said, ¡°and I found out Boojum was right. You got to study the man running. If he¡¯s a fast man, I¡¯ve got to fire it. If he¡¯s a slow man, I¡¯d lob it, just get him by a step.¡±

? Dandridge wasn¡¯t just a stellar fielder, he was a great hitter, too. He made a lot of contact, and his Hall of Fame plaque notes his ¡°stellar bat control.¡± He adeptly hit the ball to all fields, after his first professional manager, Candy Jim Taylor of the Detroit Stars, re-made his approach. When he first signed on with the Stars as a 19-year-old, Dandridge considered himself a home run hitter.

¡°Jim Taylor was the smartest man. ¡ He took my light bat away from me. He got me out there for one solid week and learned me to hit that ball: spray here and there,¡± Dandridge said.

Dandridge focused more on going the other way, instead of only pulling the ball. The strategy paid off: he wasn¡¯t much of a slugger, but Dandridge got a ton of hits. He hit over .315 for his career in the Negro Leagues, though he didn¡¯t hit many homers.

? In addition to his storied Negro Leagues career, Dandridge also had a strong showing in Mexico, playing eight seasons with teams in Mexico City and Veracruz. On those teams, he found himself in the company of other Negro Leagues greats like Josh Gibson, Willie Wells and Leon Day.

We don¡¯t have complete statistics from Dandridge¡¯s time playing in Mexico, or any part of his career, but there are bits and pieces, which are unofficial. By those, in 1943, he hit .370 and led the league with 90 RBIs. In 1948, he led the league with a .369 average.

? The next big stop in Dandridge¡¯s career was back in the United States. In 1949, he signed with the New York Giants to play for the Minneapolis Millers, the club¡¯s Triple-A team. He played four seasons there, from 1949-52, hitting .310 or better in each of the first three and winning the American Association MVP in 1950, when he hit .311, a year after being named the league¡¯s Rookie of the Year.

His production in Minneapolis seemed like it might have merited a callup, but that never came. However, his time with the Triple-A club gave him the chance to mentor a future Hall of Famer: Willie Mays. The two were teammates in 1951, hitting consecutively in the lineup.

¡°Ray Dandridge was like my father,¡± Mays once said, citing a story about the third baseman charging the mound after a pitcher tried to bean Mays, even though the pitcher was much bigger and more than five inches taller than Dandridge.

Dandridge and Mays were even together when Mays got the call to the big leagues. The two were at a movie when Mays was asked to return to the hotel, as he¡¯d been called up to the Majors.

? Plenty of accolades came Dandridge¡¯s way, too. He was a three-time All-Star in the Negro Leagues, an All-Star when he played in Mexico, and he was inducted into the Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame in Monterrey in 1989, two years after he was inducted to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

He was a player-manager once, too, for the New York Cubans in 1949.