Celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Negro Leagues

May 9 marks Negro League Day in the State of Maryland

The 2020 season marks the 100th anniversary of the start of the Negro Leagues, when Rube Foster gathered owners of several independent African American baseball teams in Kansas City, Mo. and established the Negro National League.

While African-Americans had played baseball in Baltimore for nearly 40 years at that point, it would be several more years before the city had a team that was admitted to one of the two professional leagues that began in the 1920s.

First the Baltimore Black Sox, and later the Baltimore Elite Giants, represented the city over a span of 27 seasons. The Black Sox, who began as an independent team in 1916, were charter members of the Eastern Colored League in 1923.

Though they finished second in three of their six seasons in the ECL, it wasn’t until the league disbanded and the Black Sox joined the American Negro League that they found ultimate success.

Led by three newcomers to the infield -- second baseman Frank Warfield, manager-shortstop Dick Lundy and third baseman Oliver Marcelle -- the Black Sox won the league title in 1929 with a 53-29 record. Nicknamed the “Million Dollar Infield” after Philadelphia A's “$100,000 Infield” of the 1910s, the Black Sox players earned far less than their moniker, as Negro League pay averaged about $5,000 -- and several thousand less than the average Major Leaguer’s salary.

Despite the success in 1929, the Black Sox returned to being an independent team in 1930.

Meanwhile, in Nashville, the Elite Giants were having a difficult time drawing fans for their Negro National League team. They moved to Columbus, Ohio, in 1935, then to Washington in 1936, before moving further north, to Baltimore, two years later.

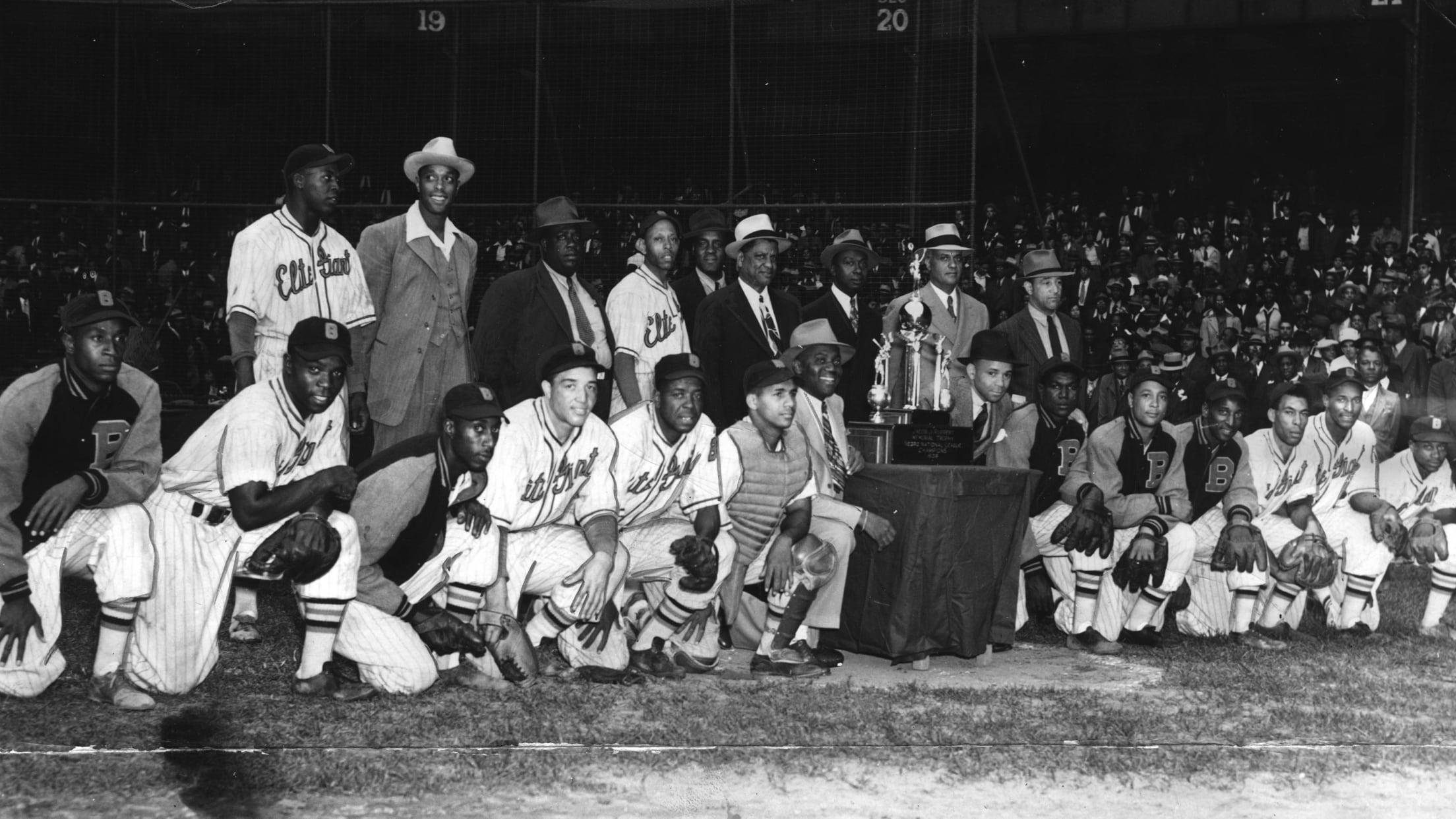

The Elites (pronounced “EE-lites”) had only modest success before moving to Baltimore, but became one of the National League’s best teams over the next 13 seasons. They finished among the top three teams nine times and won two titles in a league dominated by the Homestead Grays, who were the New York Yankees of the Negro Leagues.

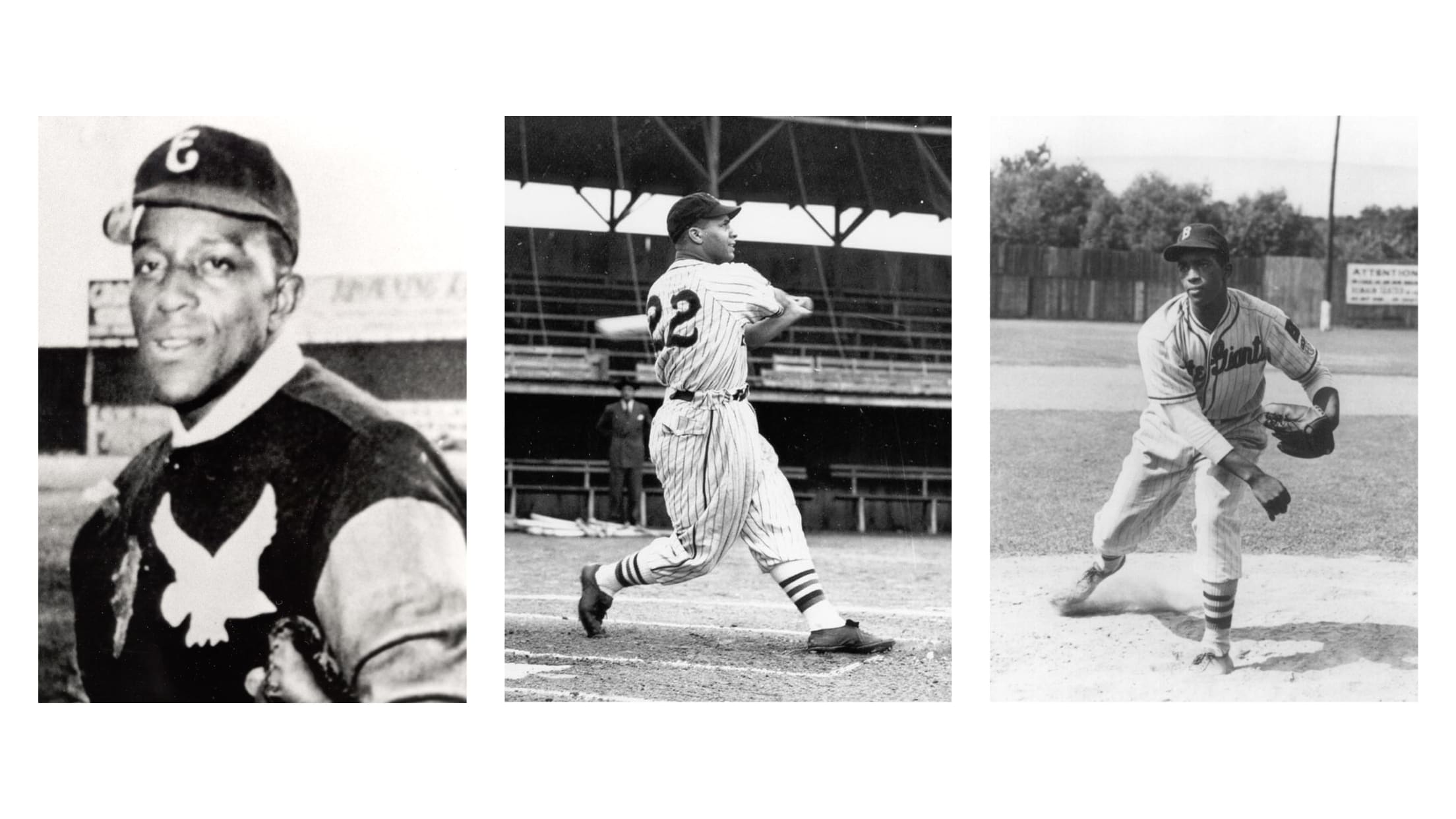

Among the team’s outstanding players were player-manager Biz Mackey, veteran pitcher Leon Day, and a young catcher, Roy Campanella, all of whom would be elected to Baseball’s Hall of Fame -- Mackey and Day as Negro League greats, and Campanella as a three-time MVP and eight-time All-Star in the majors with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Two other Elite Giants signed with the Dodgers and became National League Rookies of the Year -- pitcher Joe Black and second baseman Junior Gilliam.

After a lackluster first season in Baltimore, the Elite Giants finished in third place in 1939, and advanced to the four-team Negro National League playoffs. After beating the Philadelphia Stars in the first round, the Elites met the Grays in the best-of-five final. They split the first four games before Baltimore won its first Negro League title with a 2-0 win at Yankee Stadium in the fifth game.

In 1949, the Elites won the Eastern Division and beat the Western Division champion Chicago American Giants in a playoff for their second title. The team finished second in 1950, but financial problems forced the owners to sell the team, which was relocated to Nashville in 1951 and dissolved after that season, as the integration of the previously all-white Major League Baseball in 1946, with the Dodgers’ signing of Jackie Robinson, was beginning to take its toll.

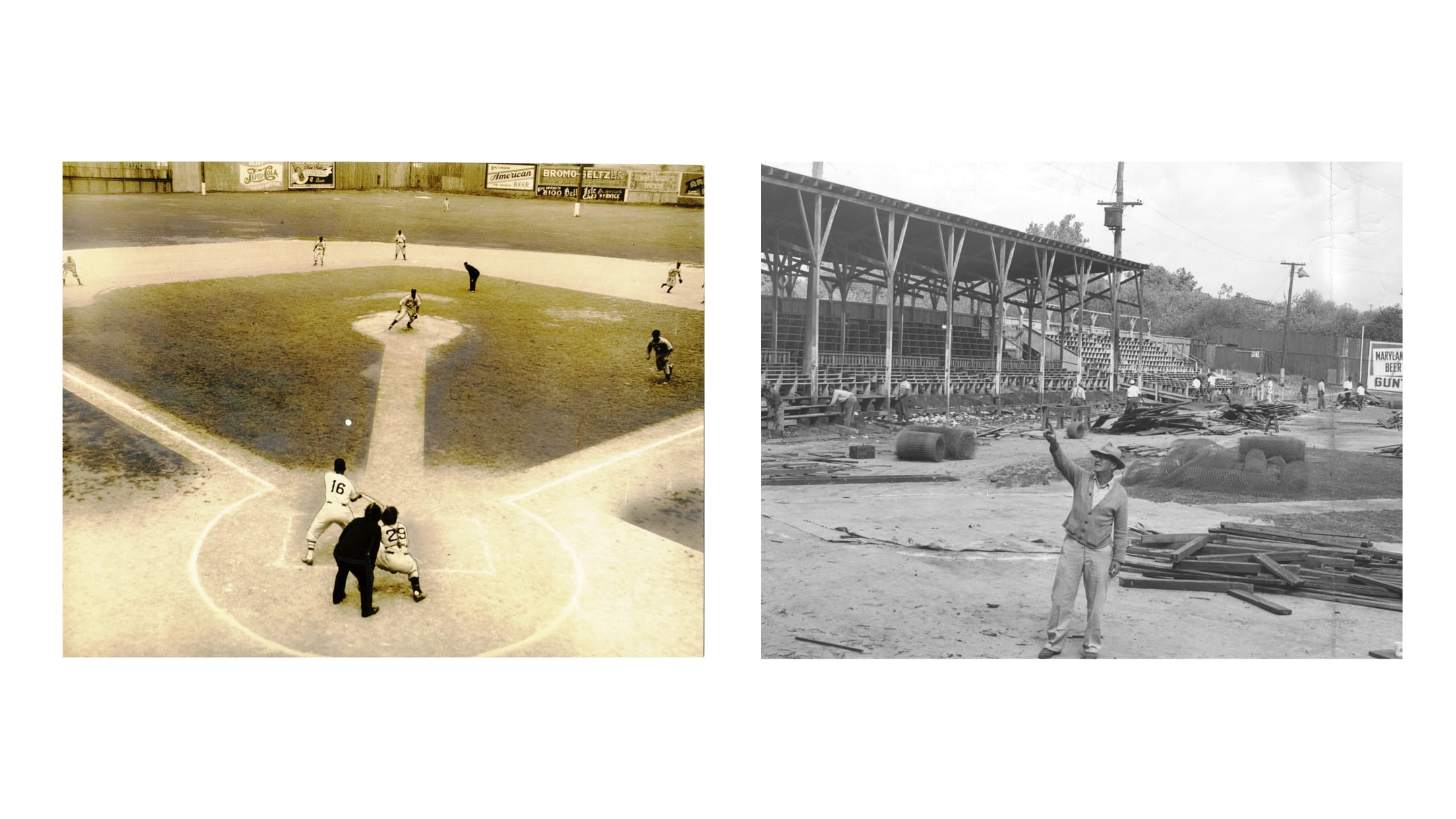

One of the problems for Negro League teams was finding a suitable ballpark in which they could both play and draw fans, while still being able to make money. In Baltimore, as in many cities, minor league team owners were often either reluctant to rent their ballparks to the black teams, fearing animosity from the mostly white neighborhoods in which they were located, or charged rents that were exorbitant. The Black Sox and Elite Giants played only a handful of games in the myriad of stadiums which were home to minor league teams throughout their nearly four decades in Baltimore.

The Black Sox, in fact, spent much of their time at ballparks not far from Oriole Park at Camden Yards. Founded in 1916 as an independent team, they played at Westport Park, which was located at the intersection of Clare Street and Annapolis Road (just south of I-95 and east of Maryland 295), from 1917 through 1920.

The following year, they moved their games several blocks north to Maryland Baseball Park, located at the intersection of Bush Street and Russell Street (north of I-95 and east of Maryland 295), about a mile south of Oriole Park at Camden Yards. (The exact location of Maryland Baseball Park was not even known until an old aerial photograph taken by the Maryland Port Administration nearly 90 years earlier was discovered in 2013.)

When the Elite Giants came to town in 1938, they took up residence at Bugle Field, which was located at what is now Edison Highway and Federal Street in east Baltimore. Following the 1949 Negro American League championship series in which the Elites beat Chicago, Bugle Field was torn down.

Though barnstorming teams would continue through the 1950s, it is now nearly 70 years since the end of the formal Negro Leagues.

The legacy of the Negro Leagues is personified by the Hall of Famers who began their career there before being signed by Major League teams: Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Larry Doby, Monte Irvin, and Ernie Banks, in addition to Campanella and Robinson. Nearly two dozen other Negro League stars are enshrined in Cooperstown -- most having played before baseball’s integration, or too late in their career to draw a look from Major League teams.

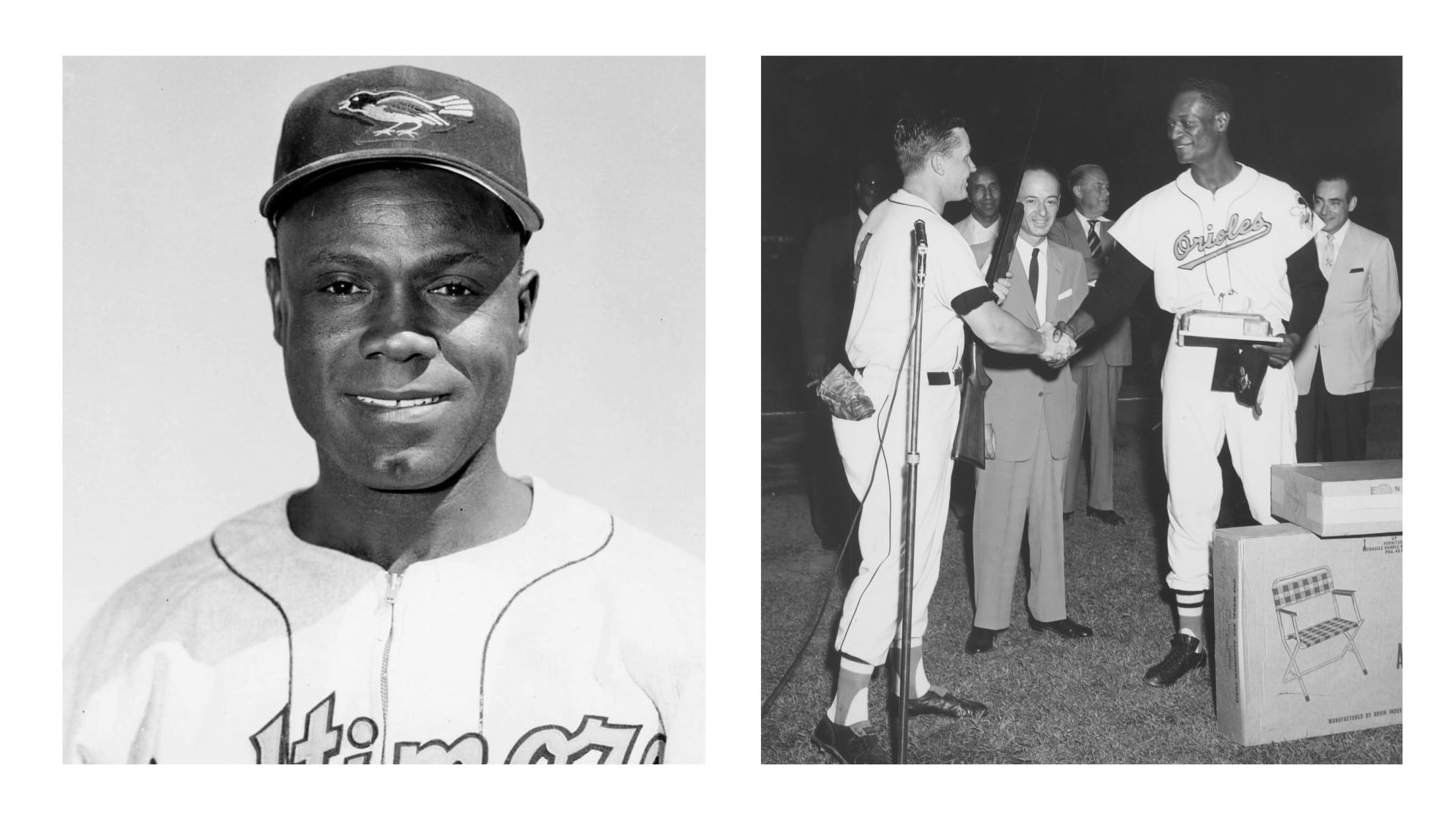

In all, about three dozen former Negro League players reached the majors -- including two former Baltimore Orioles: first baseman Bob Boyd and pitcher Connie Johnson -- before Major League Baseball’s integration helped bring the Negro League era to a close.

In 2009, sixty years after the Elite Giants won their last championship, a bill was signed into law proclaiming the second Saturday in May as “Negro League Day in the State of Maryland.”

Soon after, the Hubert V. Simmons Museum of Negro Leagues Baseball was established, named after longtime Baltimorean and former Elite Giants pitcher Bert Simmons. In 2014, the museum moved to the Owings Mills branch of the Baltimore County Library, where it is free and open to the public during regular library hours.

A century after its inception, the legacy of the Negro Leagues lives on -- an essential part of baseball and Maryland’s history.