Twenty-five years later, Donnie Elliott is still teaching changeups.

Not that changeup, mind you. Elliott doesn't teach that changeup to anyone anymore.

Says the man who gave birth to one of the most unhittable pitches of the past quarter century: ¡°It¡¯d be hard to teach a high school kid to throw that."

In the Houston suburb where he grew up, Elliott now serves as pitching coach at Deer Park High School. He points out that Trevor Hoffman's changeup technique is too nuanced for any high school pitcher to replicate without thousands of hours of tinkering. Plus, Elliott adds, ¡°There's only one way to throw a four-seam fastball and a few ways to throw a curve, but there are a thousand different ways to throw a changeup.¡±

In each word, it¡¯s evident how deeply Elliott loves pitching. He gets particularly wistful recalling the nights after he pitched: When he lost, Elliott was too exasperated to sleep. When he won, he was too invigorated. Years later, Elliott would come to realize that both were part of the same emotion, so he reminds his pitchers often: ¡°Embrace it all. You don't get that in the real world. You don't get that working nine to five."

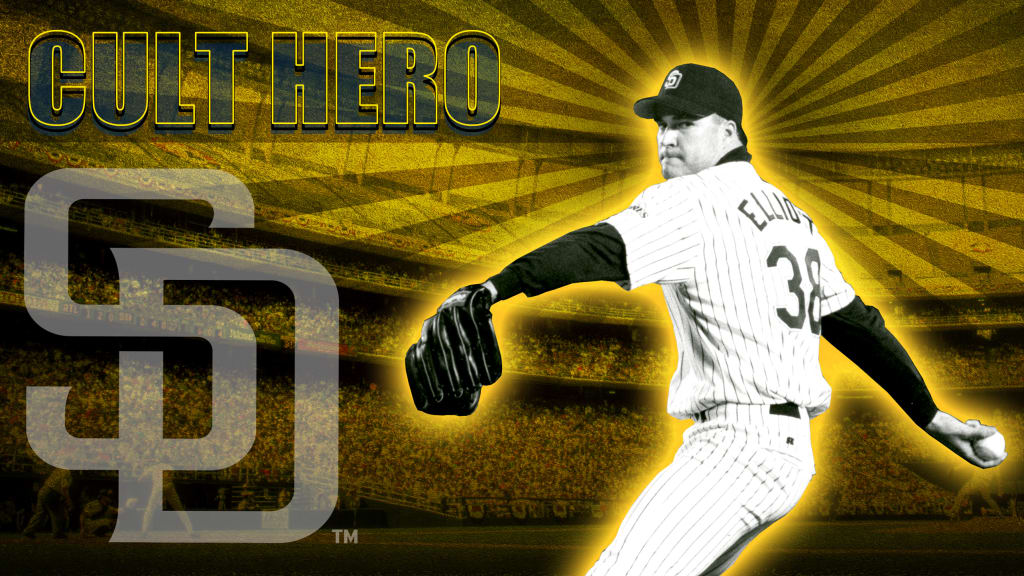

A baseball lifer, Elliott has given decades to the game he loves. He spent 10 seasons in the Minors and a few more in independent ball. In 1994, Elliott made it to the big leagues, and he did so again, briefly, in '95. He posted a (very respectable) 3.09 ERA in 31 appearances before elbow and shoulder trouble halted his career.

As such, Elliott's career is a classically forgettable one. He was a middle reliever on two bad Padres teams. And yet, for all the years Elliott gave to the game, his contributions will be forever defined by a singular conversation down the left-field line at Jack Murphy Stadium in the summer of 1994 -- a conversation that set Hoffman, one of the best relievers in the sport¡¯s history, on course for Cooperstown.

"There's no chance," says Hoffman, "that I could've ever envisioned what that changeup would become."

Before it was Hoffman¡¯s changeup, it was Donnie Elliott's.

From the ashes of the fire sale

In June 1993, the Padres hired Randy Smith as general manager. Then-owner Tom Werner gave an edict to slash payroll by the Trade Deadline, so Smith got to work. Over the next month and a half, he executed the three trades that came to define the era of Padres baseball infamously known as "the fire sale."

Smith landed rookie Trevor Hoffman in a five-player deal that sent Gary Sheffield to the Marlins. He also acquired Andy Ashby, Brad Ausmus and Doug Bochtler from the Rockies for Bruce Hurst and Greg Harris. At the time, those deals drew plenty of scorn (more for what they represented than for the players acquired). But both trades unquestionably worked out.

"We made three trades during the so-called fire sale," Smith recalled. "Two of the three turned out in our favor."

The one that didn't? As Smith notes, it made quite an impact on the organization anyway. On July 18, 1993, Elliott arrived from Atlanta with Vince Moore and Melvin Nieves in exchange for Fred McGriff.

"I was ecstatic,¡± Elliott said. "I was obviously with the Braves, and unless somebody got hurt, I wasn't going to beat out John Smoltz, Tom Glavine and Greg Maddux."

Given what McGriff accomplished in Atlanta, the Padres clearly came out on the wrong end of the deal. But Elliott reported to Triple-A Las Vegas, and the following spring, he grew close with Hoffman -- another product of the fire sale.

That April, Elliott made his debut against the Phillies, who roughed him up over 2 2/3 innings in his only big league start. Afterward, Elliott moved to the bullpen, where he and Hoffman became throwing partners. As two young right-handers trying to stick in the Major Leagues, Elliott and Hoffman routinely bounced ideas off each other.

"Your throwing partner turns into a pitching coach, to a degree," Hoffman said. "He was super open about information and how he tweaked things. It was always a really good conversation, even when we weren't talking changeup. It just seemed to always hit home."

Changing things up

Elliott didn't always throw that changeup. He used a standard circle-change for most of his Minor League career. But when he reached Triple-A, he encountered a daunting challenge in the form of one of baseball's preeminent sluggers.

¡°I just couldn't get Jim Thome out,¡± Elliott said. ¡°That¡¯s the reason I developed that grip.¡±

Elliott¡¯s changeup worked just fine against right-handed hitters. But against power-hitting lefties -- specifically Thome -- it tailed into their wheelhouse. After tinkering with different grips, Elliott found one that caused the pitch to drop more sharply. He pinched his pointer finger and his thumb together at the seam, gripping nearly the entire baseball with his remaining three fingers. Within a year, Elliott was using that grip in the big leagues.

Around the same time, Hoffman was coming off a shoulder injury he sustained while diving on the beach during a volleyball game. Hoffman could still pitch, but his fastball velocity dipped from the high-90s to 92-93 mph. Suddenly, Hoffman found himself in dire need of a go-to putaway pitch, and he started picking the brains of other pitchers on the staff.

"We're sitting in the outfield one day, and he asks me, 'Hey, how do you throw your changeup?'" Elliott said. "It was the most normal conversation.¡±

That famed chat has assumed its place in Padres folklore. When San Diego retired Hoffman's No. 51, Elliott was a distinguished invitee. He was also on hand for Hoffman's Hall of Fame induction in 2018 -- a class that, fittingly, featured Thome and Chipper Jones, Elliott¡¯s Triple-A teammate.

But the unspoken reality of that conversation between Hoffman and Elliott is that it wasn't special. In any given baseball season, pitchers have dialogues nearly every day. Hoffman and Elliott had dozens of similar conversations. Then again, those dialogues almost never bear fruit like this one did.

"I remember it being instantaneous," Hoffman said. "I tried it, and three or four throws in, I got some good action. I didn't have to baby it. I didn't have to change the way I was throwing it. I just used the grip, and I was like, ¡®Man, that feels really good.¡¯

"Within a day or two, I was using it in a game, and that wasn't really normal -- to go into a big league game and use something you're not familiar with and take a chance."

Hoffman tweaked the pitch to his own liking. He held it deeper in his palm than Elliott did. He also added pressure on the ball with his thumb and pointer finger. The pitch vaulted Hoffman to another level. Using almost exclusively a fastball-changeup mix, he saved 20 games that season with a 2.57 ERA and 68 strikeouts in 56 innings.

Over the next decade and a half, Hoffman's changeup only got better. It broke late, and it broke sharply. He threw it for strikes in hitter¡¯s counts, and he threw it below the zone to put them away. Hoffman would retire as the sport¡¯s all-time saves leader. "Master of a mystifying change-up," is the first line on his Hall of Fame plaque.

'That's your calling'

As Hoffman's career veered toward superstardom, Elliott's veered toward its conclusion. A serious shoulder injury cost Elliott the final month of the 1994 season. The following spring, after the strike, the Padres planned to ease him into action, and Elliott opened the year on the disabled list. The team's first road trip was through Colorado, where Elliott would throw a bullpen session before leaving on his rehab assignment.

"I am throwing maybe the best bullpen I've ever thrown," Elliott recalled. "In my mind, I'm 100 percent back. I'm throwing hard, my control is there, I'm ready. Then I start throwing some sliders. I threw one slider, and I felt my elbow pop."

Elliott would come to realize he'd been overcompensating for shoulder soreness by putting extra strain on his elbow. It would cost him the 1995 season, save for a two-inning appearance in late September. Elliott says he felt 70 percent, yet he pitched scoreless ball, striking out Ellis Burks to cap a 15-4 victory over the Rockies. He turned 27 later that night. Elliott wouldn¡¯t pitch in the big leagues again.

The Padres released Elliott the following month, but his shoulder and elbow injuries persisted during Minor League stints with the Phillies and Rangers, plus two seasons in independent ball.

"I hung on too long," Elliott said. "I kept trying to come back, because I kept seeing guys, and I'm like, ¡®Man, I know I'm better than that guy, and he's in the big leagues.¡¯ It was like fool¡¯s gold."

Elliott was out of baseball by 1999. But the enduring part of his legacy remained.

"After I'd been released by the Padres, I remember I came home one night after going out," Elliott said. "It's about two o'clock in the morning, and I'm half-tanked, watching ESPN, and it shows Trevor, and he's striking out guys with that changeup.

"I remember turning to my buddies and saying, 'I taught him that! I taught him that!' They're like, 'Yeah, whatever.'"

Life after baseball is rarely easy, and it certainly wasn't for Elliott.

"I wasn't bitter," he said. "But I lost touch with a lot of guys I played with and I kind of distanced myself from the Major League guys. Look, I never would've had a 20-year Hall of Fame career. But I could've had a 10-12-year, middle-relief-type career. I'll be honest, it was real hard. That was a tough pill for me to swallow."

Elliott¡¯s Major League contract included college tuition for his post-playing career, so he returned to San Jacinto College, then received his bachelor¡¯s degree from Houston-Clear Lake. Around that time, a roommate asked if he was interested in coaching. Elliott hadn¡¯t thought about it. Turns out, he was.

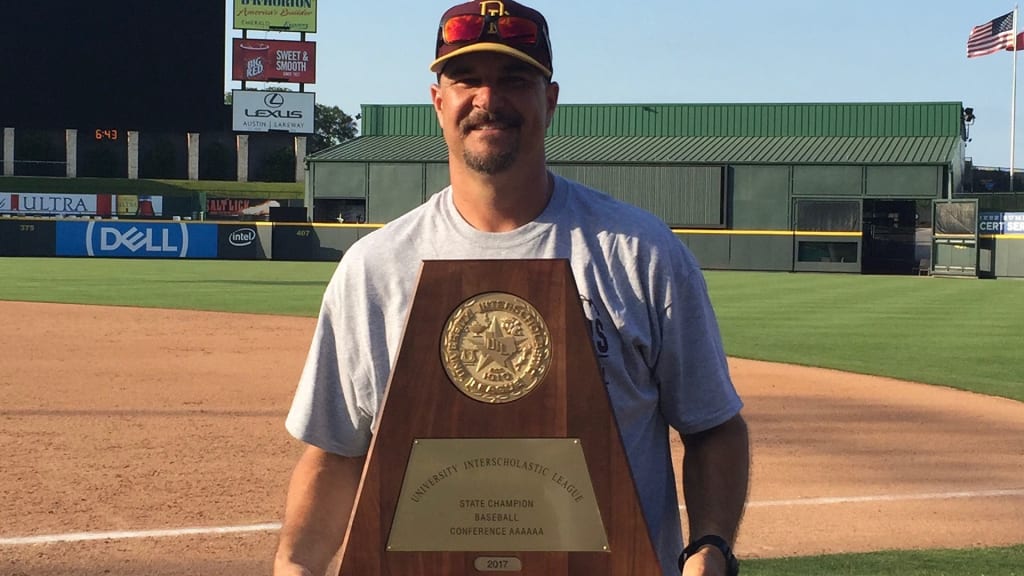

In 2002, Elliott accepted a job as pitching coach at South Houston High School. After 10 seasons there, including eight as head coach, he moved to Deer Park, where his school reached No. 1 in the country in ¡®16, then won a 6A state title in '17. Perhaps it was the natural extension of a playing career in which Elliott is known better for what he taught than for how he pitched.

"It really does resonate," Elliott said. "That's your calling. God has a plan, and this was my plan, and I've been fortunate to have some really, really good high school pitchers come through."

Twenty-five years after that significant conversation with Hoffman, Elliott laughs about the strangeness of it all. All those years spent honing his craft, and his career is defined by pregame chit-chat. He¡¯s fine with that.

"If I'd never gotten hurt and I played eight to 10 years, and that was all I was known for, it probably would've told me I wasn't very good," Elliott said. "But it doesn't bother me at all. Teaching Trevor that changeup, he obviously took it where he's gone, and it's really given me a lot of publicity. I got to go to the Hall of Fame with him. I got to be there when they retired his number.

"If I¡¯m being honest, I wish I was known for having a 10-year career, playing in a World Series, this and that. But -- you know what? -- this is cool, too."